America now looks like Rome before the fall of the Republic

Let us take a lesson from the history books

From the early Middle Ages until just a few decades ago, every educated person had to study the history of Greece and Rome. There's a reason for that, and there's a reason why it's a shame we no longer do so.

It's not just that history holds important lessons. It's that we live in a time built by dead men who preceded us. America is a constitutional republic. Its governing institutions were imagined and bequeathed to us by a number of men, and all those men studied the history of Greece and Rome, as did the philosophers and writers and statesmen they took inspiration from, and those that these men took inspiration from. This democracy we live in is like a piece of foreign machinery we are supposed to operate. If you're not a mechanic, you wouldn't try to fix your car without first trying to read some sort of instructions. In order to understand how our republic works, we need to understand the thoughts of the people who built it. We have to understand where they were coming from.

The Founding Fathers of the United States, and the Enlightenment philosophers they learned from — again, the people whose machine we are supposed to keep running — were obsessed with Greece and Rome. The reason why speeches from politicians keep referring to America as an "experiment" in democracy, why there is this sense that they were trying something daring and precarious, is because they lived under the shadow of Rome.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The common belief until the American founding was that democracy was destined to fail. A political system that promises formal equality can't bear the strain of a system that will always have inequalities of status, however you try to legitimize them. In a true democracy, demagogues will win over the people with fatuous promises and showy acrobatics, and accrue enough power to destroy the very democracy that is the source of their power. (Stop me if that sounds familiar.) The reason why they believed this was because that's exactly what happened with Rome. Hence the saying "A Republic, if you can keep it."

If we know something about the fall of the Roman Republic, we know vaguely about Julius Caesar, about how he was a popular general who used his support within the military to effect a coup. The coup then led to a civil war in which the strongman who prevailed, Augustus, thought he would do very well with the powers Caesar had claimed for himself.

If we know a little more, we know that Caesar was not just a successful general, but a canny politician, who used his political victories not just to command the personal allegiance of the legions, but to build a populist political power base at home. We might also be faintly aware that by the time Caesar could attempt his coup, the Roman Republic was already exhausted, with a complacent elite fattened by centuries of military victory and the attendant spoils.

But what historians now refer to as the crisis of the Roman Republic had a deeper, class-based component. Like all republics, Rome understood itself through the prism of the myth of its own overthrow of tyrannic rulers and the establishment of a, ahem, more perfect union. Like all national myths, this was only partly true.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In reality, Roman society was divided into two classes, the patricians and the plebeians (words that still carry meaning today, although more faintly so); three if you count slaves, which you obviously should, although they were less active politically than the other two classes.

The patricians were the aristocracy. They were large landowners, in an era where the source of economic power was land. What's more, while much of Italy was in theory public land, in practice patricians could farm those lands and keep the proceeds as if it was their own property. The fact that the patricians could rely on slave labor to farm this land made it even more profitable for them, even as it squeezed the plebeians out of the jobs they might have had farming. This fundamental equality between a landowning patrician class and the economically insecure plebeians is the most important thing to keep in mind about the history of the late Roman Republic.

What about the political system? Well, as is well known, Rome was run by a Senate, but the Senate was actually made up of patricians. To oversimplify, the Senate was like a legislative branch, which nominated the consuls who ran the executive. Did the plebeians not have a voice? The plebeians were represented by elected officials called tribunes, whose main power was the ability to propose legislation and to veto the Senate. The plebeians were most often wealthy patricians themselves, since it was the only way to be active in politics, but they were patricians with the common touch, and good tribunes, like good politicians, knew how to appeal to their constituencies.

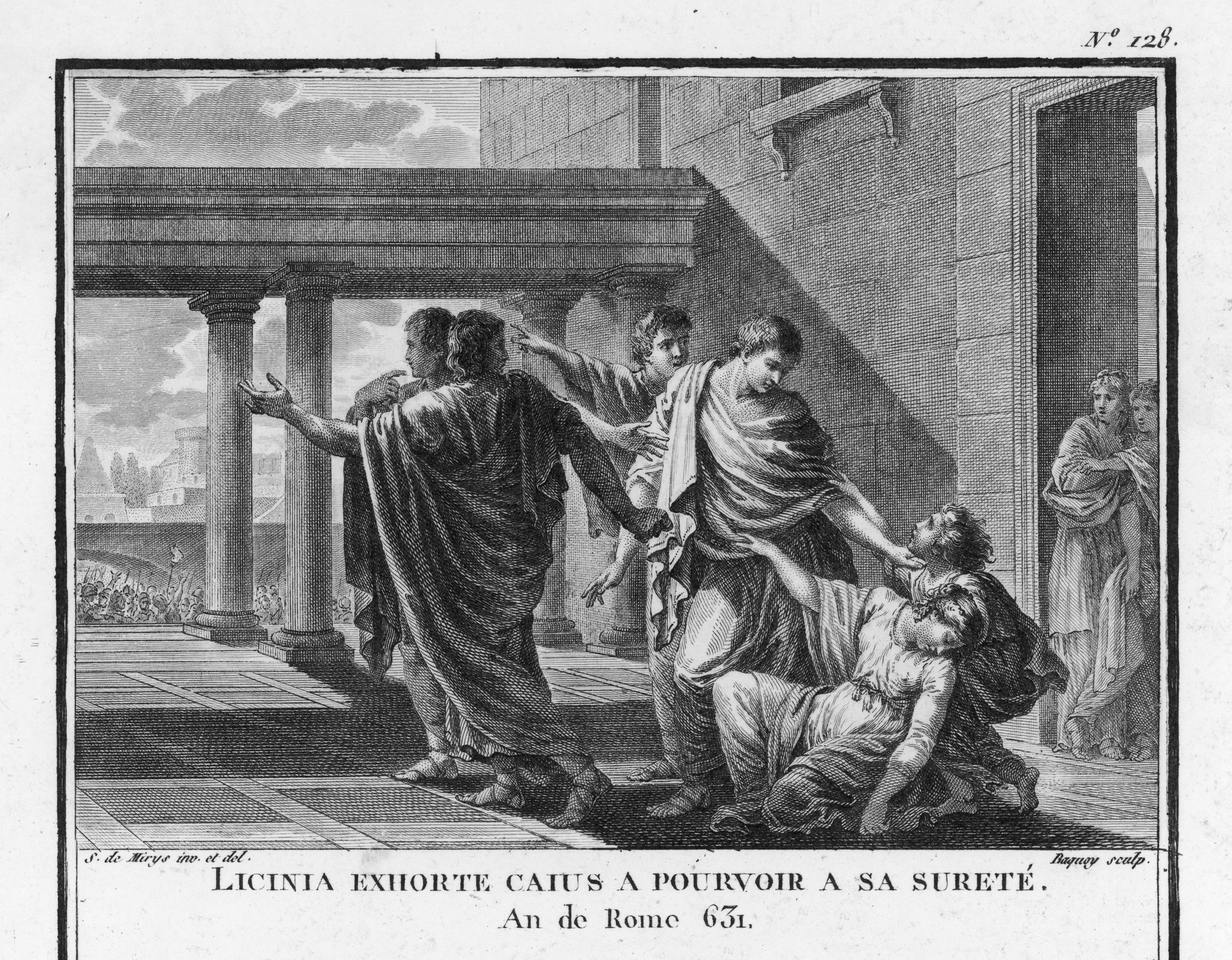

In the late second century BC — decades before Caesar actually rolled around — this crushing inequality gave birth to a political crisis. Two brothers, Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, tried to implement various reforms to rebalance the inequality, including redistributing land and distributing grain to the Roman poor. How did it go? Well, to put a long story short, Gracchus eventually committed suicide rather than fall prey to lynching by a mob raised up by a patrician consul to stomp him down by force.

The failure of the Gracchi (plural of Gracchus) did two things: The first was to re-establish the precedent of using force to settle political disputes. And the second was to entrench the class divisions at the heart of Roman society, since Rome's complex system of checks and balances (plus the sheer obdurateness of the aristocratic class) couldn't fix the problem. Of course, Rome's aristocrats did not believe themselves to simply be defending their pocketbooks. Rome, after all, was one of the world's most sophisticated civilizations, and its aristocracy was highly educated. It believed that in defending its privileges, it was defending itself from a, well, plebe, that was without a doubt uneducated and coarse, and held beliefs contrary to what it believed to be the values of Rome. In this background, Rome's government, increasingly implicated in foreign wars and maintaining an empire, had to become more and more militarized and to raise taxes to keep up its expenses.

Because those conflicts were so deeply entrenched, Rome kept lurching from social to political to constitutional crisis year after year, decade after decade, so that by the time a popular strongman came along, the Republic was like a ripe fruit waiting to be plucked.

All of which brings me to our current situation. Have you noticed that millions have left the labor force? That people without college degrees are increasingly locked out of the economy? That the globalized, meritocratic system rewards a small elite while leaving everybody else behind?

Now, it is not yet the time for a Caesar. It is not even yet time for the Gracchi, I don't think. Although there has been an increase in political violence, it is nowhere near the level of the 1960s. And while America's economy could certainly be doing a lot better, it could also be doing a lot worse — indeed, it has done best out of the global recession than practically any other major economy.

But the parallels are there, aren't they? There may not be grain riots, or large landholds, but there is definitely a patrician class, and a plebeian class, and they are definitely at loggerheads. And the inability of the political and economic system to deliver an outcome that leaves both classes doing well keeps intensifying the conflict.

On Tuesday, America rejected a patrician and elected a tribune. Let us hope we see some genuinely Gracchian reforms, and let us hope they work this time. Because if not, I fear that, though I might not, my children will one day see a Caesar cross the Potomac.

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.

-

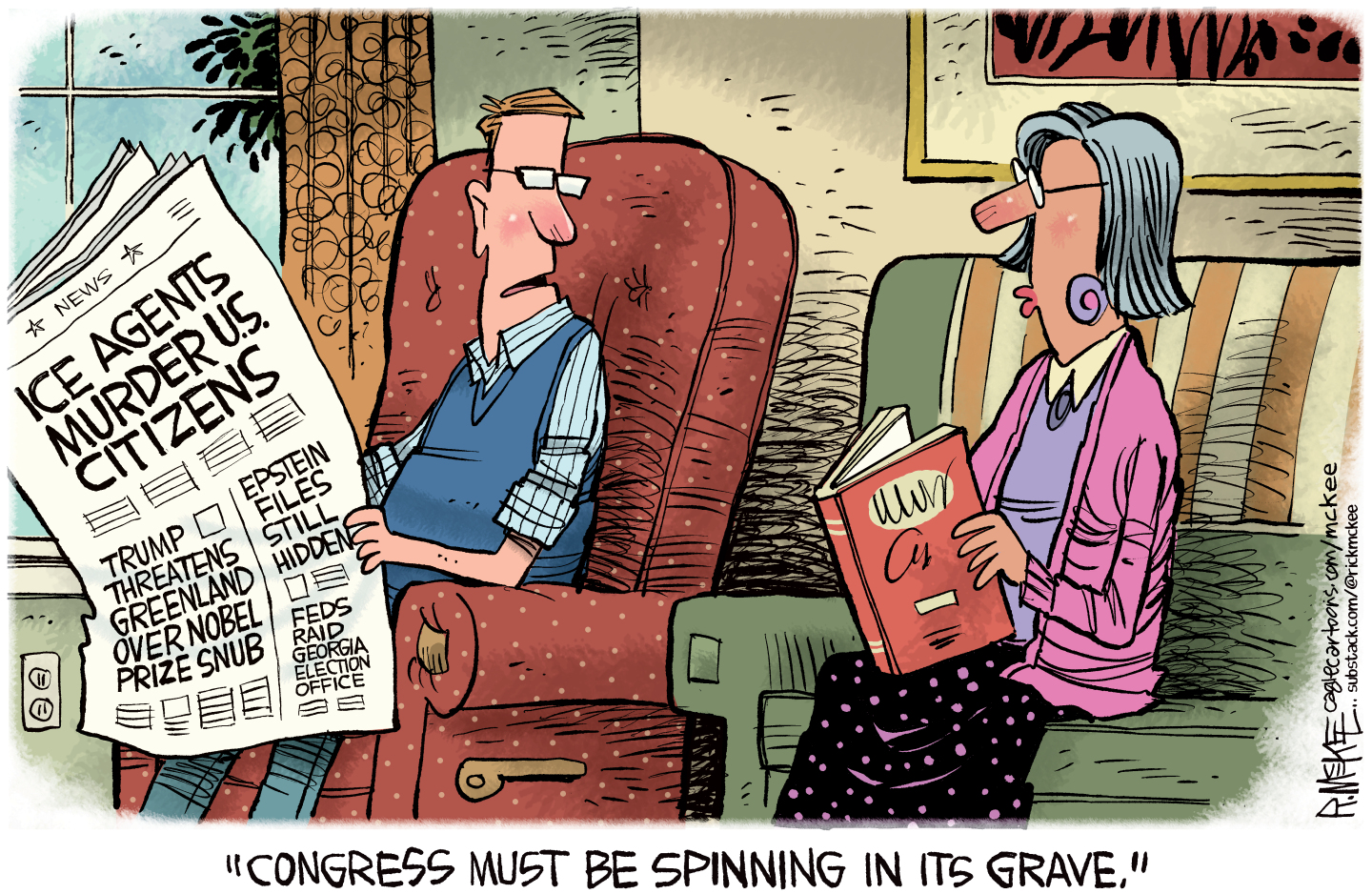

31 political cartoons for January 2026

31 political cartoons for January 2026Cartoons Editorial cartoonists take on Donald Trump, ICE, the World Economic Forum in Davos, Greenland and more

-

Political cartoons for January 31

Political cartoons for January 31Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include congressional spin, Obamacare subsidies, and more

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred