Westworld's greatest trick

No, it's not a plot puzzle — it's the way this terrific drama tugs at our emotions

(Warning: Spoilers about Westworld abound.)

What if Westworld's puzzles are just a bit of sleight of hand?

On Sunday, the HBO series revealed that Bernard Lowe (Jeffrey Wright), the sad-eyed number two to park director Robert Ford (Anthony Hopkins), is both a host and a murderer. It was a stunning plot twist, but one that was quickly eclipsed online by something that eagle-eyed fans spotted. Why did Bernard say he had no idea the facility existed, they asked, if the audience previously saw him question the ranch girl Dolores there? The likely answer is that Bernard wasn't Bernard at all in those scenes with Dolores — he was most likely Arnold, Ford's partner who allegedly died some 34 years ago. In others words, the show is probably operating in two or more different time periods — just like fans' "multiple timeline" theory contends.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Now, I admit to loving this kind of predictive sleuthing as much as anyone. The trouble is, obsessing over these puzzles can make it tough to think about the show in a more organic way. If Westworld has a problem, it's that its mysteries so completely engage our code-cracking reflex that the show's terrific drama gets short shrift.

This makes sense: Empathy is tricky in Westworld because we're specifically instructed not to feel it. That the hosts are lobotomized or beaten shouldn't affect us in the least! We are like the parks' guests: The hosts are there to be raped or destroyed at our pleasure, so go ahead and enjoy it. Westworld floods you with permissiveness and bludgeons you with the freedom to do anything. But outsourcing your moral code to Delos, Westworld's parent corporation, turns out to be an exhausting ethical premise.

In fact, the show is shot in order to make this impossible. We do feel for the hosts.

Bernard's existential agony as he processes that his back story never happened, that he isn't real, was excruciating to watch. More painful still was Ford's order that he stop emoting. And yet the sequence let us off the hook, by shortening our grief on his behalf — how can you sympathize with something that feels nothing? — and then sliding into horror. The shock of Theresa's death partly overwrote our experience of the psychic bludgeoning Bernard just received. But not completely.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Or take Maeve, the bordello-madam-turned-rebel who's overtaxing our distinctions between guest and host. Felix falls under her spell, and so do we. Unlike Bernard, Maeve never gets reduced to her robotic essence. Even when she shuts down from the shock of seeing her consciousness digitally mapped out, she doesn't stop emoting, and we're not given permission to look away or translate her into a figure of horror. (Yet, anyway.)

This is all to say that our artificial distance from the hosts, which was never great, is collapsing. If and when the multiple timeline theory gets confirmed, there will be no escaping a Westworld where tragedy isn't just possible but overwhelming.

I admit it: I held out against the multiple timeline concept because I found it too unbearably sad. It would mean, among other things, that Dolores has some kind of "awakening" twice, and that her first bid for autonomy and self-determination was detected and rerouted for three decades into a grim simulacrum of itself. If Dolores and William are happening 30 years earlier than almost everything else in Westworld — if she "woke up" to a degree that let her shoot, change into pants, imagine herself as something other than a damsel, and have consensual sex only to be shoved back into the blue dress and sunny bewildered damselhood for 30 more years — well, that's horrifying. It's awful to the point that it would have been hard to keep watching, had I known.

And it only gets darker. Teddy's arrival in town and interactions with Dolores seem to be based, beat for beat, on Dolores' meet-cute with William, right down to the retrieval of the dropped can of milk. Teddy, in other words, appears to be some kind of "William" replacement to keep Dolores stuck in place forever, waiting for his return. If her breakthrough got her disciplined, that drive, that memory of William, was cruelly left intact. Whatever Dolores and William did in the past — which probably connects to the white church and likely involved disobeying Ford — seems to have shaped her punishment: Thirty years of a hell-loop where she's not just the damsel, but the damsel who never gets saved. Dolores is forever waiting for Teddy/William to come back, and her reward is perpetually reliving the joy of a brief reunion followed by the pain of losing him, and her family, and herself.

That's more than brutal, it's sadistic. And it must change our reading of Ford, who claims to have nothing but a distant, fatherly feeling toward his creations. "They cannot see the things that will hurt them," he tells Theresa. "I've spared them that. Their lives are blissful. In a way, their existence is purer than ours, freed of the burden of self-doubt." It's an ugly boast, especially when you consider how emptily saccharine Dolores' affect is during her subsequent 30 years in her loop — how firmly she's been rewound to a retrograde form of female "purity" that's there just to be ravaged — and compare it to her determined seriousness, her agency, and her sincere, sad, self-aware smiles in her scenes with William.

Westworld banks on emotional whiplash. That we're too wrapped up in the show's mysteries to see it might be Westworld's greatest trick.

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

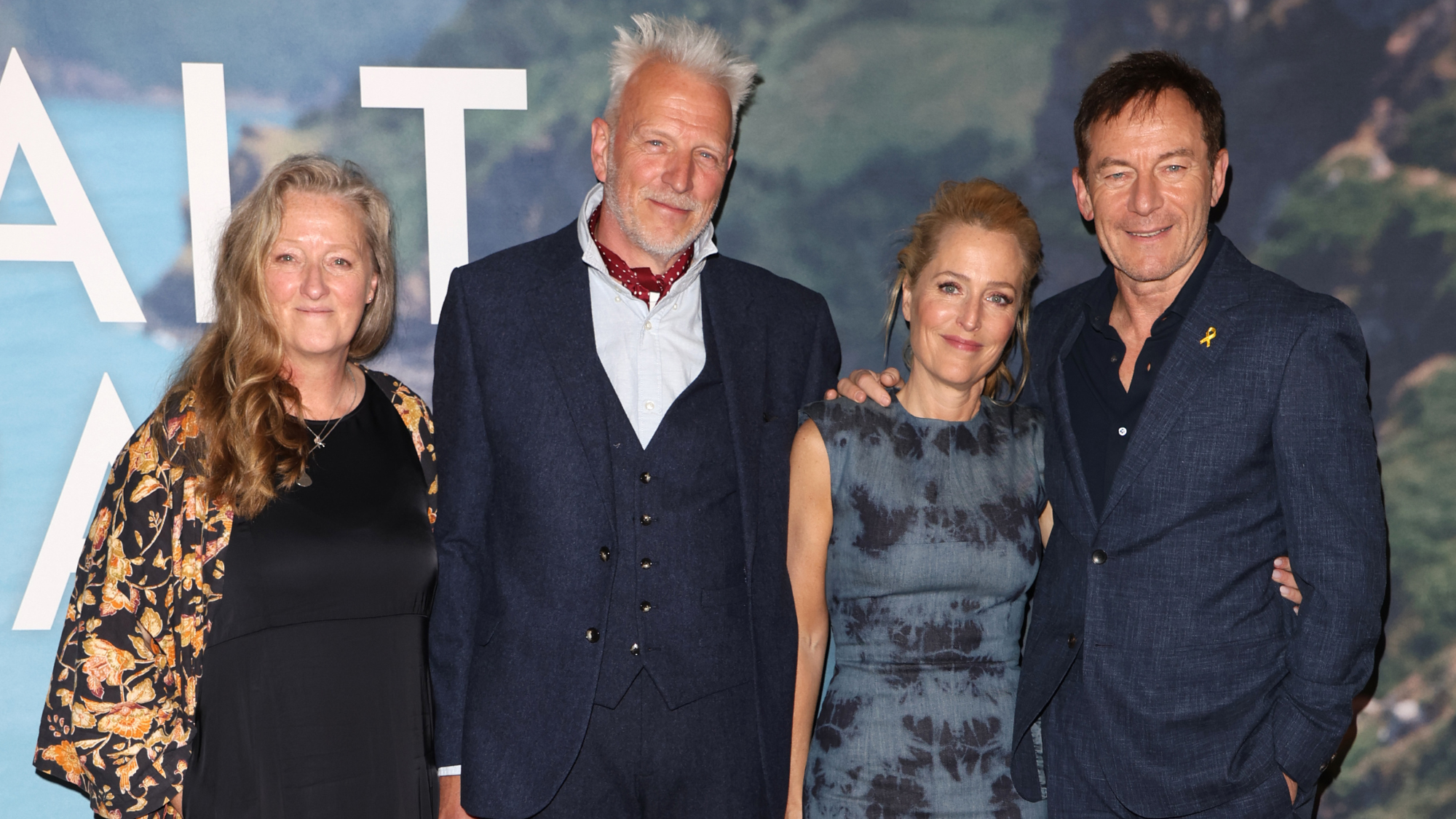

The Salt Path Scandal: an ‘excellent’ documentary

The Salt Path Scandal: an ‘excellent’ documentaryThe Week Recommends Sky film dives back into the literary controversy and reveals a ‘wealth of new details’

-

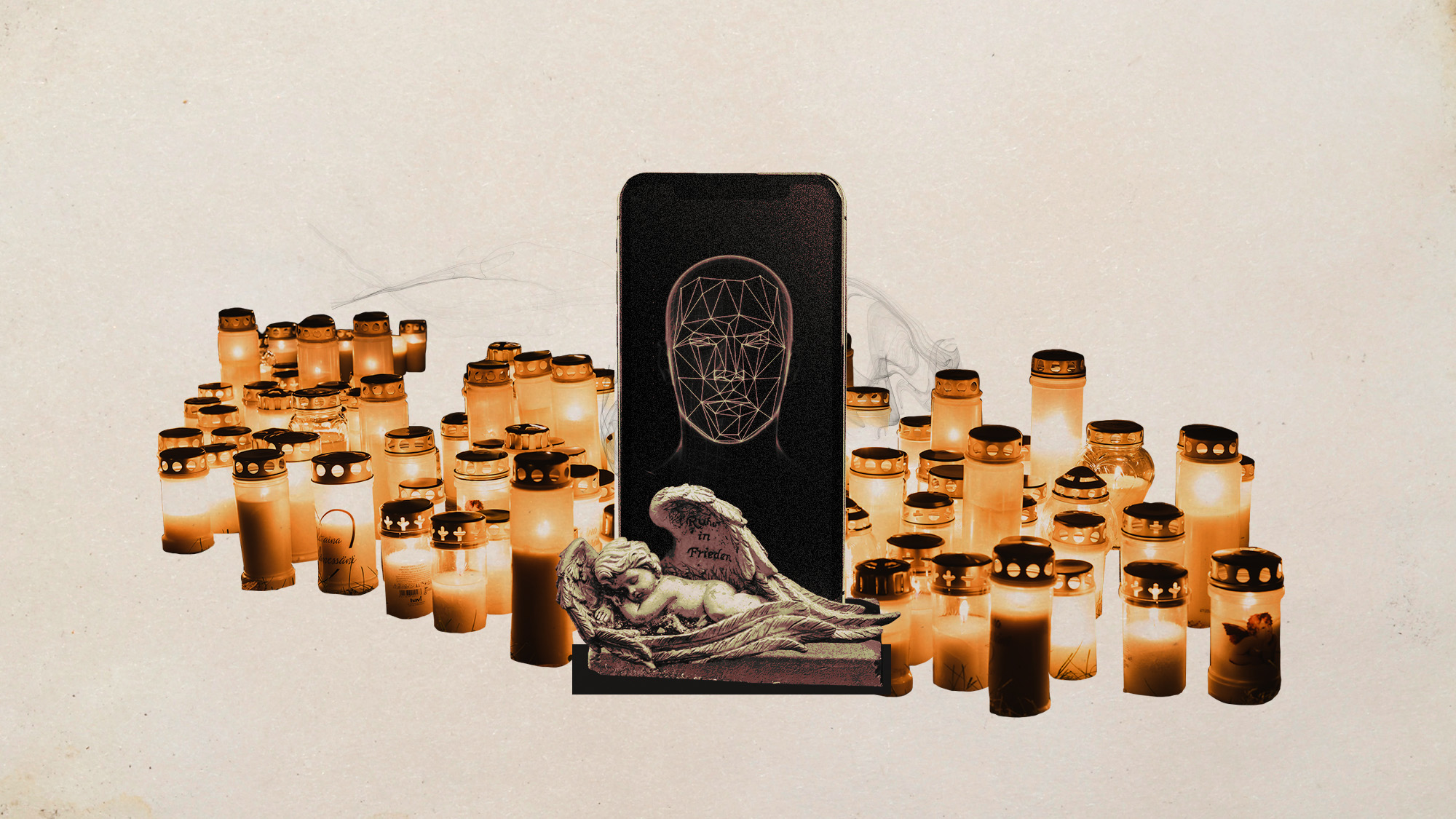

AI griefbots create a computerized afterlife

AI griefbots create a computerized afterlifeUnder the Radar Some say the machines help people mourn; others are skeptical

-

Sudoku hard: December 17, 2025

Sudoku hard: December 17, 2025The daily hard sudoku puzzle from The Week

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.