Hollywood's long goodbye to the Obama era

From Ghostbusters to Barry, this year's movies paint an accurate picture of the nation's political mood

On the evening of Nov. 10, two days after the 2016 presidential election, I was sitting in a theater in St. Paul, Minnesota, watching Contemporary Color, the opening night film of the Sound Unseen festival. A document of David Byrne's 2015 hybrid of a rock concert and a high school color-guard exhibition, the movie is a tuneful, energetic salute to musical and cultural diversity, featuring dozens of fresh-faced teenagers of every size, skin color, and sexuality, who've all apparently found a nurturing community in competitive flag-waving. Maybe I was still shell-shocked from the electoral results, but as I watched the documentary — and felt moved by the talent, grace, and inclusivity of this rising generation — I thought to myself, "This feels like the last dispatch from an America that no longer exists."

2016 was always going to be the end of the Barack Obama administration. But if the Democrats had held the White House, it's possible that "the Obama era" as a cultural concept would've continued on for the rest of the decade. Instead, the annual look back at the year in entertainment has begun to take on the form of a long goodbye. Considering the movies in particular, certain films, stacked alongside each other, now seem to tell a larger story about both the hope of our nation and our deep, dangerous divisions — and how Obama has presided over all of that, whether he intended to or not.

This was a year with not one but two biopics about the young Obama — both of which are quite good. Barry (which debuted on Netflix on Dec. 16) follows the future president as an alienated college student in New York in the early '80s, dating a wealthy white woman while exploring his black identity by trying to make friends in the inner city. Meanwhile, Southside with You catches up with Obama at the end of the decade in Chicago, as gets to know his fellow fledgling lawyer and wife-to-be Michelle, while working within the black community to make sure that the local government was hearing the concerns of the poor and working class.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

More than just hagiographies (though both are also that to some extent), Barry and Southside with You both feel like unexpectedly timely attempts to reckon with the roots and endurance of the Obama phenomenon. As liberals are in the throes of an angry election post-mortem, in which "identity politics" has been used as an epithet, these movies show how a politician could become an inspirational figure by representing a myriad of Americas.

These big questions — questions of what shapes us, how we each connect to the larger culture, and whether our pasts and our passions are fairly represented — have been a common theme in several of the year's best films. Those conversations form the unspoken backdrop of the Oscar-contender Moonlight, which follows a closeted gay black drug-dealer through three phases of his life. These questions also subtly animate The Fits, in which an inner-city adolescent tomboy becomes captivated by the glamorous-looking dance troupe at her local community center.

The father-son drama Morris from America is more open in its discussion of race and self, as a widower tries to explain to his hip-hop-loving teenager that he moved them both to Germany to expand their respective perspectives on the larger world. And no movie in 2016 engages with personal identity as provocatively — or relevantly — as the documentary I Am Not Your Negro, which turns the text from an unfinished James Baldwin book into a raw-nerved visual essay about America's persistent inability to reckon with the legacy of slavery.

The anger in I Am Not Your Negro is an unfortunate but undeniable part of how the Obama years will be remembered. Though Baldwin's book was reflecting on the civil rights movement, the documentary's director Raoul Peck pairs images of 1960s unrest with footage from riots and protests in the 2010s, finding a continuity between the issues Baldwin was writing about (like the urgent matter of who's allowed to be a full participant in our democracy) and the struggles today between African-American communities and the police. The chilling documentary Do Not Resist delves even further into the latter problem, examining how the increased militarization of law enforcement has disproportionately punished the poor. And films as disparate as the Nat Turner biopic The Birth of a Nation and the O.J. Simpson docu-series Made in America challenged the idea that it's possible to transition to a "post-racial" nation.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

For every 2016 film that was sensitive, thoughtful, or inspiring on the subject of how we define ourselves in the early 21st century, there were a handful of others disputing the notion that we have the luxury to navel-gaze. The experimental documentary The Prison in Twelve Landscapes surveys America in 2016 and finds it pockmarked with communities where the economy and other mechanisms of daily life are governed by who's being incarcerated — and who's profiting off of it. The excellent neo-western Hell or High Water tracks two desperate bank robbers who've been pushed to crime by a bad mortgage on their family ranch. The ingenious thriller Don't Breathe — which pits young burglars against an unusually handy blind man — gains some depth from the dire economic situation of its protagonists, and from taking place in a crumbling Detroit neighborhood.

The point is that the disquiet and dissatisfaction that fed the rise of President-elect Donald Trump is just as present in some of this year's best films as the feelings of pride and self-actualization that helped boost Obama to the Oval Office twice. Clearly, despite indicators of widespread prosperity and social progress in the United States, something has gone awry for a sizable chunk of the electorate — or at least is perceived to have done so. That'll all be part of the eventual post-mortem for this year and this decade. And that's not even taking into account movies like the cyber-terrorism documentary Zero Days or Oliver Stone's Edward Snowden biopic, which, in retrospect, may end up seeming like advance warnings of an age of hacking that could come to define "the Trump era."

Speaking of advance warnings, the defining motion picture of 2016 may turn out to be the female-led Ghostbusters remake, if only because the online furor over this fairly inconsequential, modestly funny exercise in '80s nostalgia mirrored the larger culture war that raged throughout the election season. The silly fights over Ghostbusters were a leading indicator of the gulf between the kind of voters likely to be passionate for Hillary Clinton because of the positive message it would send to women everywhere, and the kind of voters likely to be enthusiastic about Trump because they were sick of having icons of popular culture changed just for the sake of making some people feel better. These two camps weren't just talking past each other; they often refused to accept any possible validity of the other's position. Anyone who couldn't be convinced that Ghostbusters was harmless at worst and purposeful at best was unlikely to be persuaded to switch a vote from Donald to Hillary.

Those men and women — the ones who've been grumbling "enough" about the entertainment business' inclinations to educate and promote social goods — spoke loudly on Nov. 8. Does that mean the end of movies that offer an empowering salute to diversity? Probably not. But it may mean a loss of confidence within Hollywood that their simple messages of acceptance and tolerance are still widely welcomed. In time, as the tone of our politics changes, so might the tone of our cinema, if only because the major studios want to serve what they imagine to be their ticket-buying public.

If so, a decade from now, even crowd-pleasing science-fiction films like Arrival and Star Trek Beyond might seem very much "of their time" — due to their optimism, their salute to scholarly reasoning, and their emphasis on multicultural cooperation to solve world-ending problems. If that proves to be the case though, those who've been feeling despondent for the past several weeks over the direction of the country can take some comfort in the idea that both of those movies were very popular. Someday they'll represent the "good old days" that a future bloc of voters may begin pining to bring back.

Noel Murray is a freelance writer, living in Arkansas with his wife and two kids. He was one of the co-founders of the late, lamented movie/culture website The Dissolve, and his articles about film, TV, music, and comics currently appear regularly in The A.V. Club, Rolling Stone, Vulture, The Los Angeles Times, and The New York Times.

-

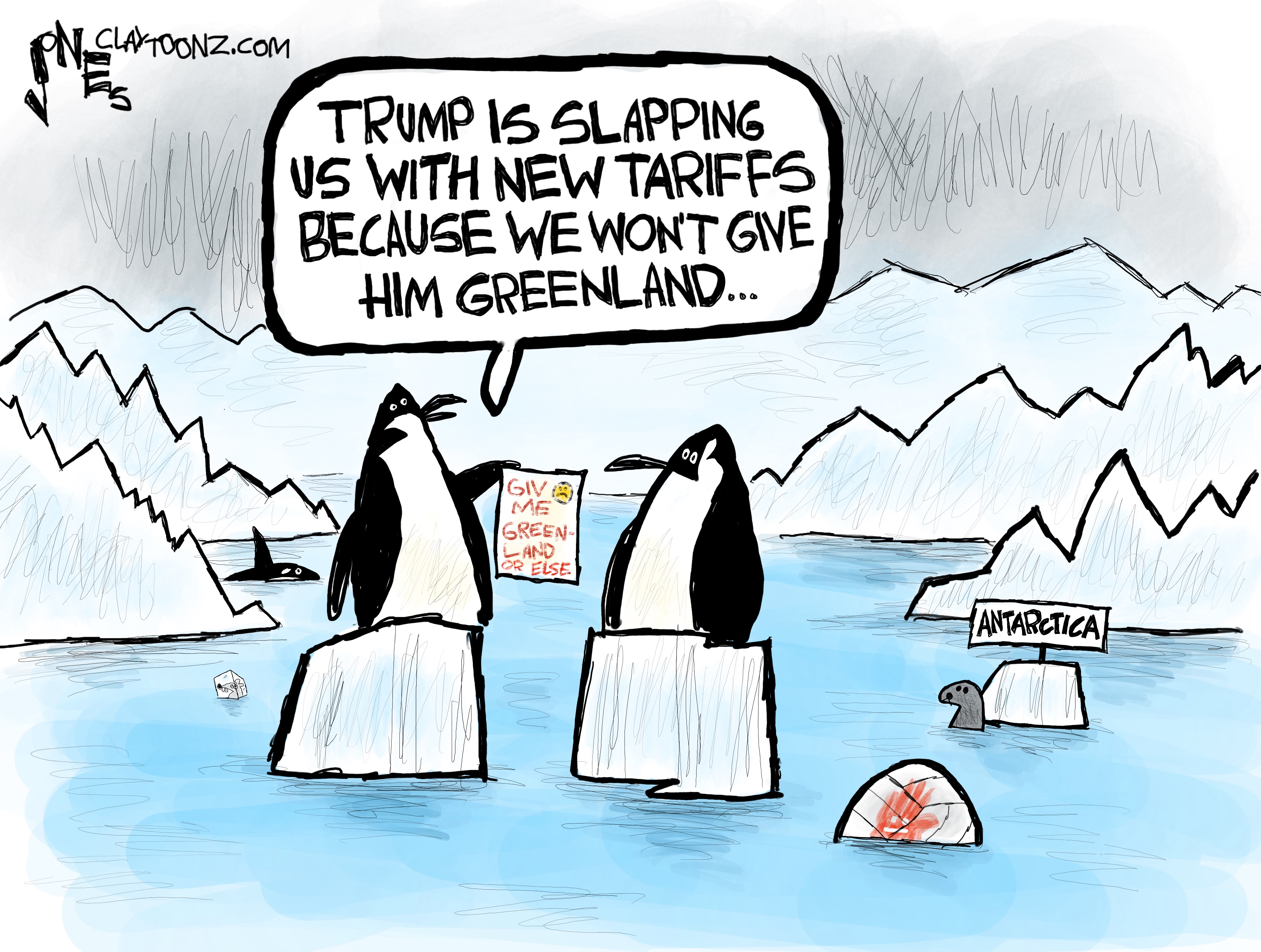

Political cartoons for January 19

Political cartoons for January 19Cartoons Monday's political cartoons include Greenland tariffs, fighting the Fed, and more

-

Spain’s deadly high-speed train crash

Spain’s deadly high-speed train crashThe Explainer The country experienced its worst rail accident since 2013, with the death toll of 39 ‘not yet final’

-

Can Starmer continue to walk the Trump tightrope?

Can Starmer continue to walk the Trump tightrope?Today's Big Question PM condemns US tariff threat but is less confrontational than some European allies

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred