The rise of the Rorschach candidate

What do you see in your politician? Whatever you want.

What do Barack Obama and Donald Trump have in common? What about François Fillon and Theresa May?

Not much, you might say. But I've noticed something recently in global politics: It seems that increasingly, the political systems in the West produce winning national candidates who skillfully craft an image that allows them to be all things to all people (or, rather, enough people). I call it the rise of the Rorschach candidates, after the infamous psychological inkblot tests in which the viewer is left to interpret his own meaning from a pattern of otherwise meaningless spatter.

For Barack Obama, this phenomenon almost became a cliché during his long-ago astonishing rise through national politics. Obama was touted as the "liberal Reagan" who would shift American politics to the left for a generation, and yet he would also be post-partisan and a compromiser.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Once in the White House, this would continue, especially in the fever swamps of the right-wing imagination. Was Obama a simpleton who couldn't give a speech without a teleprompter and needed to hide embarrassing college transcripts, or was he a Machiavellian Manchurian candidate bent on destroying America? More pragmatically, was he a progressive hero or a fundamentally incrementalist politician? Obama carefully tried to cultivate both sides of that image, and it benefited him well during his time in office.

We can see the same patterns in Trump. Here in Paris, the only French Trump-supporting friend I have is a progressive who loathed Hillary Clinton's embodiment of the establishment. This friend of mine roots for Trump to push through a massive stimulus plan. Do Trump's appeals to the alt-right make him a "far-right" candidate? Or does his support for entitlements, government-paid maternity leave, and industrial policy make him a "moderate"? Trump pushed this to an extreme, sometimes taking both sides of an issue in the same interview. And he largely got away with it.

French politician François Fillon recently stunned the French political world in his come-from-behind smashing victory in the French conservative primary. As a former prime minister to the hard-right Nicolas Sarkozy with a hard-right platform, he could appeal to conservatives, even as his personal demeanor and history as a "séguiniste," or moderate neo-gaullist, make him acceptable to moderates and centrists.

In British politics, Theresa May has benefited from this duality as well: Her premiership will be defined by Brexit, which she has vowed to doggedly pursue, even as she kept relatively quiet during the campaign leading up to the vote. While Brexiteers might not trust her, they see her as someone they can work with, as moderate Tories see her as one of them.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This quality becomes all the more striking once you consider those Rorschach candidates' adversaries, who were all sharply defined. Mitt Romney doubled down on being the Mr. CEO candidate, playing down his admirable life as a beloved family man and diligent church minister, a soft side that, in retrospect, he might have done well to emphasize. Clinton had become defined early, almost inescapably, as the candidate of elite self-dealing. In the French conservative primary, Alain Juppé and Sarkozy clearly saw themselves as the candidate for the moderate and hard-right lane, respectively, and worked as hard as possible to cast themselves in those roles.

In a way, this phenomenon is as old as politics itself: Being all things to all people, if you can pull it off, is the definition of a winning political strategy. But there's a distinct sense that the payoff for being an amalgam of many political aspirations has increased over the past few years. Some of this could be attributed to how media-dependent our politics have become. In the French primary, Fillon and Juppé faced off as the conservative and moderate candidate, respectively, but this was all PR. When Juppé was prime minister, he was known for his hard-line stances, facing down massive strikes that paralyzed the country in 1995, and Fillon has a track record in government as an incrementalist. It's perfectly — and scarily — easy to imagine a parallel universe where the exact same men with the exact same track records and 95 percent of the same positions become cast in the opposite roles.

All of this might be heartening, in a sense: By being all things to all people, you give yourself the widest political berth once in office. The racist fringe salivates over Trump even as Democrats cautiously reach out to him. But in another sense, it's a dispiriting reminder of just how little substance there is in our political campaigns.

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.

-

What to know before turning to AI for financial advice

What to know before turning to AI for financial advicethe explainer It can help you crunch the numbers — but it might also pocket your data

-

Book reviews: 'The Headache: The Science of a Most Confounding Affliction—and a Search for Relief' and 'Tonight in Jungleland: The Making of Born to Run'

Book reviews: 'The Headache: The Science of a Most Confounding Affliction—and a Search for Relief' and 'Tonight in Jungleland: The Making of Born to Run'Feature The search for a headache cure and revisiting Springsteen's 'Born to Run' album on its 50th anniversary

-

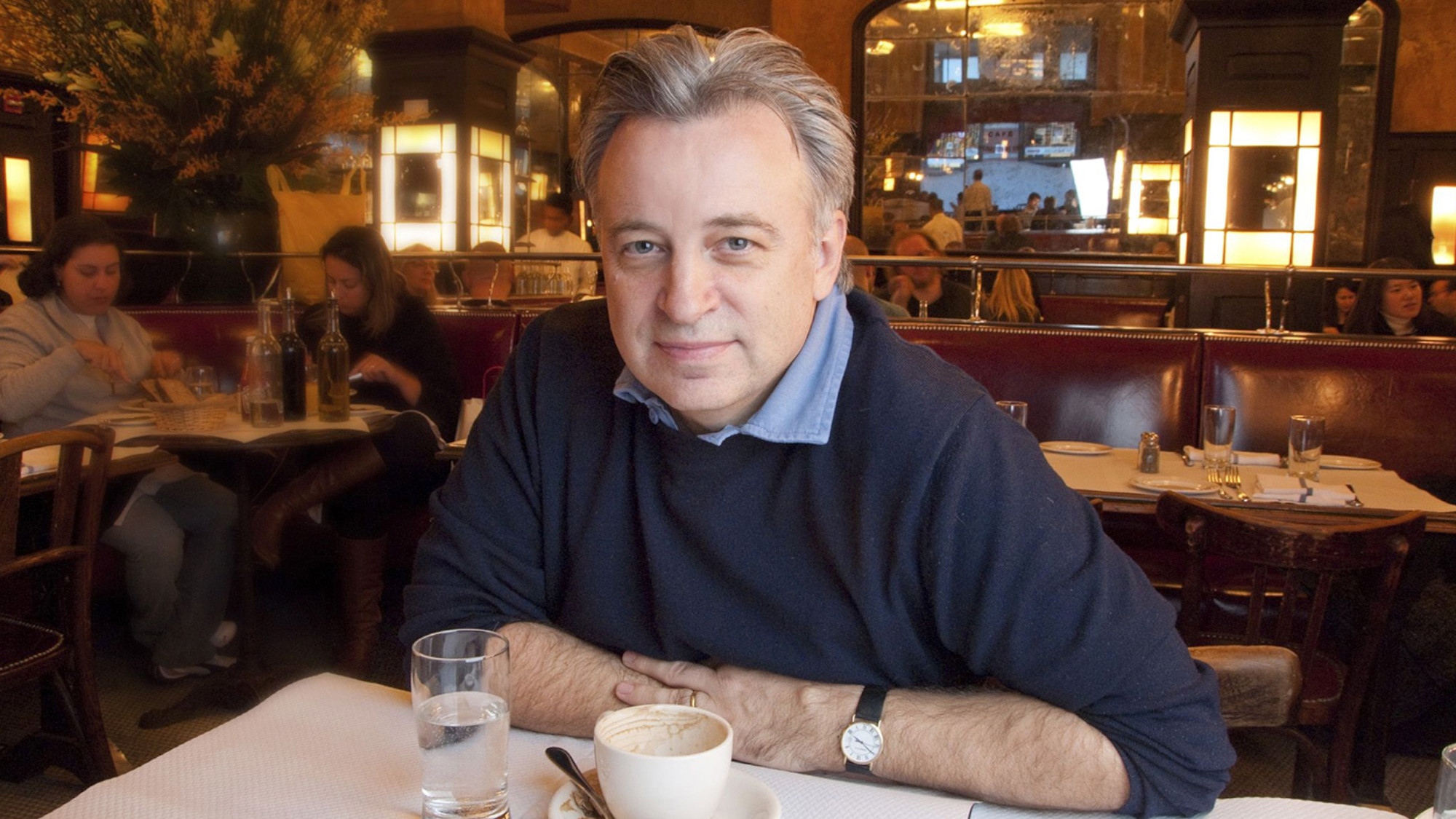

Keith McNally' 6 favorite books that have ambitious characters

Keith McNally' 6 favorite books that have ambitious charactersFeature The London-born restaurateur recommends works by Leo Tolstoy, John le Carré, and more

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event