How the good ideas in Paul Ryan's ObamaCare plan are overwhelmed by all the bad ideas

It's a poison pill with sugarcoating

Last week, House Speaker Paul Ryan and his fellow Republicans released a new paper that attempts to flesh out the details of their ObamaCare replacement.

On the one hand, it's chock full of absurd statements like "There is no saving ObamaCare. It cannot be fixed." On the other hand, ObamaCare is far from perfect, and really does suffer from deep problems. And underneath the GOP's ideological hyperventilation are a few ideas that really could help.

For instance, ObamaCare provides subsidies, in the form of tax credits, on the health insurance exchanges so people can more easily afford coverage. In theory, this is a great idea. In practice, the subsidy system is a nightmare of byzantine complexity. There's one set of subsidies for premiums, another set for cost-sharing like deductibles and co-pays. Whether you get help depends on whether you buy the right government-approved plan. The subsidies are also means-tested — they scale up and down with your household income — so whether you qualify, and for what, depends on rifling through the minutiae of your tax forms.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It's hard to overstate what a soul-sucking hassle this is for everyone.

So Ryan and the GOP want to replace ObamaCare's tax credits with one flat tax credit — the same amount of money for everyone — that goes to every American who doesn't get their health coverage through their job or a government program like Medicare. The credits also sound like they'd be refundable. That would ensure that even the poorest Americans with little-to-no tax liability get every last cent of the credits.

It would scale up and down according to your age, but that's it. No more tests for income, and no more subcategories of categories. This sort of universalist design has several advantages: As the proposal notes, means-testing can also subtly discourage work, since the more you earn from your job, the smaller the subsidy. Treating everyone the same also builds political solidarity and makes programs harder to cut.

Unfortunately, there's also a giant caveat here. Not everyone needs the same amount of help buying health coverage and care. So if you're going to douse everyone equally with the money hose, you better make sure there's enough to cover the poorest Americans and the worst-case scenarios.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The weakness of ObamaCare's means-testing is complexity and perverse incentives. But the advantage is less spending by targeting those most in need. If you take the GOP's universalist approach, you have to spend way more to provide the same level of support. And ObamaCare's subsidies ran the federal government around $30 billion in 2016 as it is.

This is a huge political and ideological problem for the Republicans. The only thing they rant and rave about more than ObamaCare is the size of federal government spending. Ryan's paper doesn't offer specifics on how much the universal tax credit would be worth. But it's a safe assumption the GOP will solve this contradiction by just making the credit far too cheap.

Then there's the matter of what to do about Medicaid, the program that provides health coverage for the poorest Americans, the same way Medicare provides it for the elderly.

ObamaCare also expanded Medicaid, and in many ways it's been the most unambiguously successful part of the reform. But while Medicare is a fully federal program, Medicaid is a partnership between the federal government and the state governments, with both kicking in parts of the program's budget. The federal government paid almost all of the expenses of expanding Medicaid. But the basic design still means the program can be an onerous drag on state governments, forcing them into untenable budget situations and crowding out other programs.

The spirit of the GOP's fix here is a good one: They want to disentangle the state governments from this mess. But the way they go about it is, again, fatally flawed.

Rather than just take the Medicare route and fully federalize Medicaid, Republicans want to transform Medicaid into a one-way cash grant, calculated on a per capita basis, that the federal government gives the states. This comes with a host of problems. For instance, what happens if there's a recession? Would the cash grant automatically increase? The history of the idea also isn't encouraging: When policymakers tried this gambit with welfare reform in the 1990s, conservative states took the money and funneled it off to pet projects rather than spend it on the welfare enrollees who needed the help. "Why would anyone allow [the grants to states] to potentially harm the very patients they are intended to help?" the proposal plaintively asks at one point, seemingly ignorant of recent history.

Small-government zeal trips up Ryan and his fellow Republicans here, too. They rightly complain that Medicaid's reimbursement rates for doctors and providers are too low, leading to reduced networks and less care. But then they complain Medicaid's budget is "unsustainable." Well, which is it? Does Medicaid spend too little or too much?

In truth, Medicaid's budget is only a serious problem for state governments, whose spending and borrowing operate under fundamentally different structural constraints. The federal government could shoulder the burden just fine. But again, the GOP will probably resolve the paradox by making the new cash grants grossly inadequate.

This is all a running theme in GOP policymaking: Good ideas mixed in with some truly vicious notions that turn the whole package into a poison pill. And the other ideas in Ryan's paper — like nixing the tax that enforces the individual mandate or giving high-risk pools another whirl — are plain irresponsible.

In a properly functioning democracy, the need to compromise would force the GOP to stick with the good ideas and jettison the bad. As it is, Democrats' best hope is probably that some future fluke gives them back the presidency and legislative supermajorities, and they remember to steal a few Republican ideas. Just like they originally did with ObamaCare.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

6 homes built in the 1700s

6 homes built in the 1700sFeature Featuring a restored Federal-style estate in Virginia and quaint farm in Connecticut

-

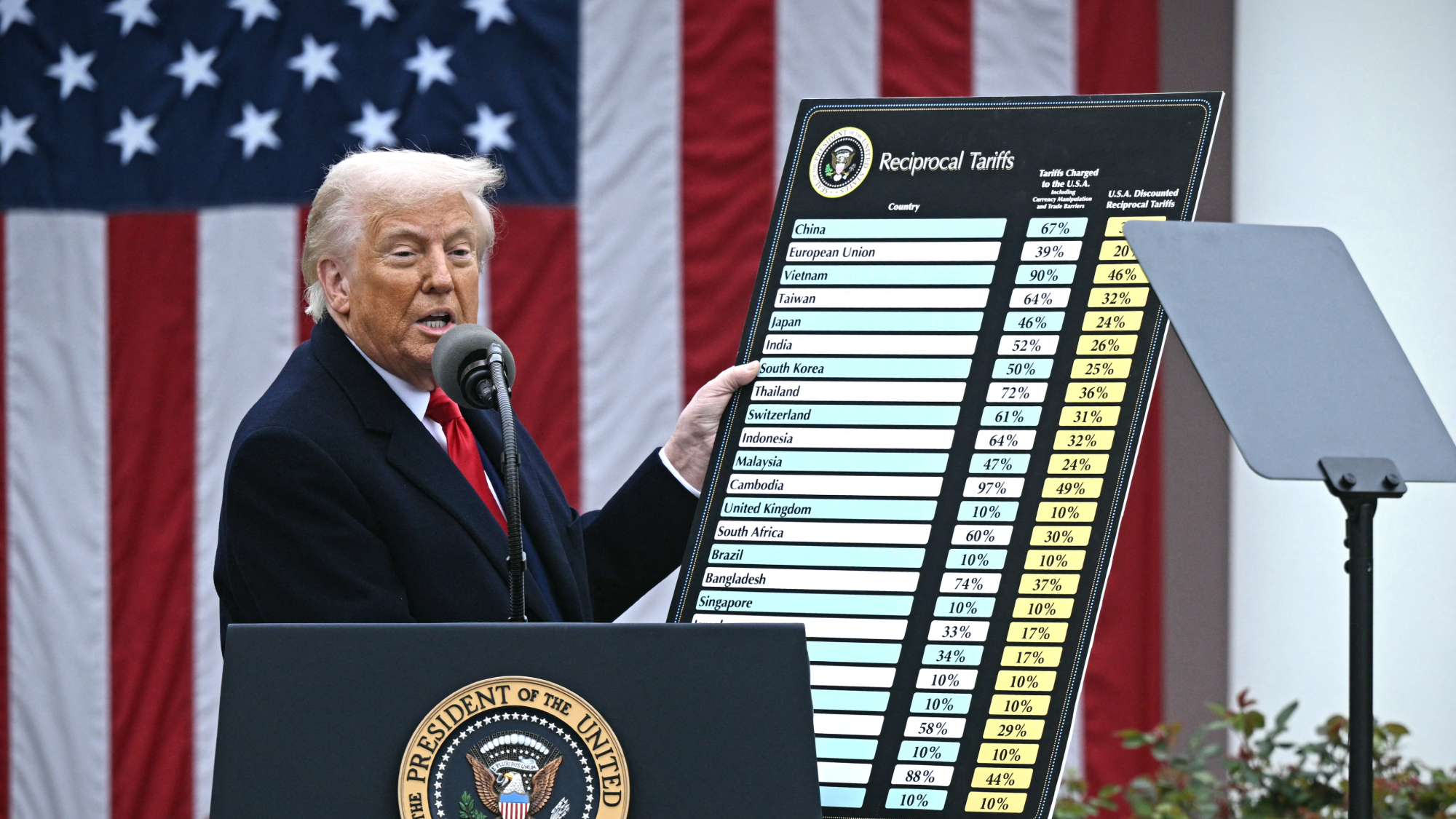

Tariffs: Will Trump’s reversal lower prices?

Tariffs: Will Trump’s reversal lower prices?Feature Retailers may not pass on the savings from tariff reductions to consumers

-

American antisemitism

American antisemitismFeature The world’s oldest hatred is on the rise in U.S. Why?

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration