Watch the Iditarod while you still can

Is this the last great race on Earth?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

You can interpret the Iditarod's motto, "the last great race on Earth," two ways.

The first goes hand-in-hand with Alaska's boast of being the Final Frontier, the last piece of untouched, unsullied wilderness in the conquerable world. In those six words, the Iditarod puts to shame lesser races like the Tour de France, the Boston Marathon, the Indianapolis 500, and turns its nose (and muzzle) up at the various ways they have sold out, modernized, and become un-great.

The Iditarod, on the other hand, is just a musher, a handful of dogs, and whatever Alaska decides to throw at them, be it moose, whiteout, or thin ice. The Iditarod is proud to be "tough," the motto says, the way the word was meant to be used.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Increasingly, though, "the last great race" might take on a hint of irony. Is this the last one? Could it be? For the third year in the Iditarod's history, the traditional starting line was moved from Willow, Alaska, to Fairbanks — 365 miles north — due to a lack of snow for the mushers' sleds.

"Alaska is heating up at twice the rate of the rest of the country — a canary in our climate coal mine," writes Eric Holthaus for Slate. "A new report shows that warming in Alaska, along with the rest of the Arctic, is accelerating as the loss of snow and ice cover begins to set off a feedback loop of further warming."

Temperatures that dropped below -30 overnight in Fairbanks prior to the official start of the 45th Iditarod might have temporarily pushed climate change from mushers' minds. Still, racers won't merge onto the historic Southern Iditarod route until they reach Ruby, Alaska, over 300 miles away from the starting line.

Many Alaskans have expressed concerns about the rerouting. "It's not the race it used to be," Steve Perrins, who owns a lodge at a now-bypassed checkpoint, told Alaska Dispatch News. "It's not half the race it used to be. They're going to kill this race, and I'm hearing it from numerous people."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But the Iditarod is not dead yet despite looking a little green around the gills. But, with the clock ticking, there could be only a few years remaining for the nearly 1,000-mile race to retain semblance to its original shape and form.

Luckily, the advancing years have also brought new ways for armchair spectators to enjoy the race. For beginners looking to break into watching the race, the rules are fairly simple:

The Iditarod begins with a ceremonial start in Anchorage, a nod to the race's beginnings as a potentially life-saving serum run in 1925 (yes, that was the one with Balto). The race then moves to the official starting line, which this year is in Fairbanks but is usually in Willow. Mushers must begin the race with at least 12 dogs and no more than 16, and they cannot cross the finish line unless a minimum of five dogs are pulling their sled. Dogs cannot be added along the trail, but they are often dropped with vets and volunteers at checkpoints along the way.

Part of the fun of watching the race is seeing where the various mushers drop out. In fact, many mushers in the race have no ambition of even finishing in first place — they just want to finish at all.

And with the safety of dogs and their humans being the number one concern of race organizers, mushers are also required to make three mandatory stops while running the approximate equivalent of a trip from Los Angeles to Portland, Oregon (Alaska, if you hadn't heard, is big). Those stops are: A 24-hour layover anywhere along the trail, plus an additional eight-hour stop somewhere on the Yukon River and at the White Mountain checkpoint.

Then there are the "only in Alaska" rules:

The best way to follow the Iditarod is online, although the Alaska Dispatch News has terrific coverage along the trail, too. While the official Iditarod website feels a little dated, there is a wealth of resources available to race watchers who might not live in, oh, Unalakleet or White Mountain.

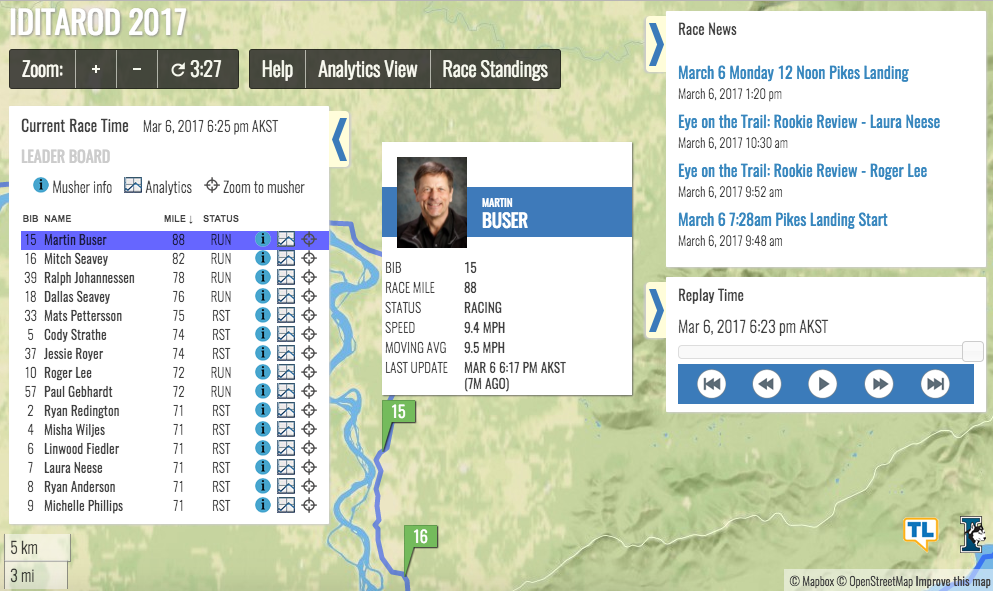

Having attended the start of the Iditarod and followed the race online for years, I can add that access to the official Iditarod GPS map is worth the $19 that it costs. While it might seem steep to the uninitiated, it is a dangerously addictive resource with real-time updates on where the mushers are and whether they are currently on the trail or resting. It even includes links to their videos and bios:

(Seven hours into the race, four-time champion Martin Buser is in the lead / Iditarod)

Of course, the Iditarod becomes even more fun when you have someone to root for. There are several familiar characters in this year's race as well as a handful of loveable rookies. Overall, the 2017 Iditarod includes 17 women and 55 men, with five previous Iditarod champions returning to the race.

Dallas and Mitch Seavey are the two names to know. The competing son-and-father duo boast back-to-back first and second place finishes respectively. Dallas has now won the Iditarod three years in a row, and is again the favorite this year. Jeff King and Martin Buser are the only other mushers in the race who can match Dallas Seavey's four total Iditarod championships, and if any of the three win this year, they'll be just the second musher ever to have won five Iditarods, tied with Rick Swenson.

Others race for a different kind of legacy: Brothers Robert Redington, 28, Ryan Redington, 33, and Ray Redington Jr., 40, are competing in the race as third-generation mushers, the grandsons of Joe Redington, Sr., who is known as the "father of the Iditarod" for having helped launch the race in 1973. "I was born to race Iditarod," said Ryan.

Another one to watch is Aliy Zirkle, 46, who ran her first Iditarod in 2001 and was a runner-up in 2012, 2013, and 2014. (Bonus: Her pup roster includes an adorable mother-daughter pair: Olivia and Olivia Junior.) Then there is Larry Daugherty, a rookie from Eagle River, Alaska, who wants to become the first person to finish the Iditarod and climb Mt. Everest in the same year. There are also the twins Anna and Kristy Berington, who have been competing against each other in the Iditarod since 2012.

But the Iditarod's long history and boasts of being the "last great race" are in jeopardy and there isn't likely to be a reversal soon. "Alaska's weather, according to one Alaska meteorologist, is 'broken,'" Holthaus writes. Climate scientists believe the Iditarod trails will keep losing snow, making it harder for the sleds to brake and therefore more dangerous for mushers and their teams. Rivers that once could be counted on to be smooth, navigable roads will continue to thaw, making passage likely impossible in future decades. The former route to Nome from Willow, up through the famously difficult Rainy Pass in the Alaska Range, could one day be dropped from the race altogether in favor of the Fairbanks trail. Someday, maybe, there won't be a race at all.

"For me, Alaska really is the last frontier. It's about people being resilient," Iditarod musher Trent Herbst told The Guardian last year. "If you are Alaskan, you are used to change — and yeah, even climate change. People will change with it."

But for 2017, at least, there will once more be an Iditarod winner and a team of dogs draped in the famous yellow wreaths of the champions.

Watch. Remember. Because one day, it really might be the last great race.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surge

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surgeIN THE SPOTLIGHT Mass arrests and chaotic administration have pushed Twin Cities courts to the brink as lawyers and judges alike struggle to keep pace with ICE’s activity

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.