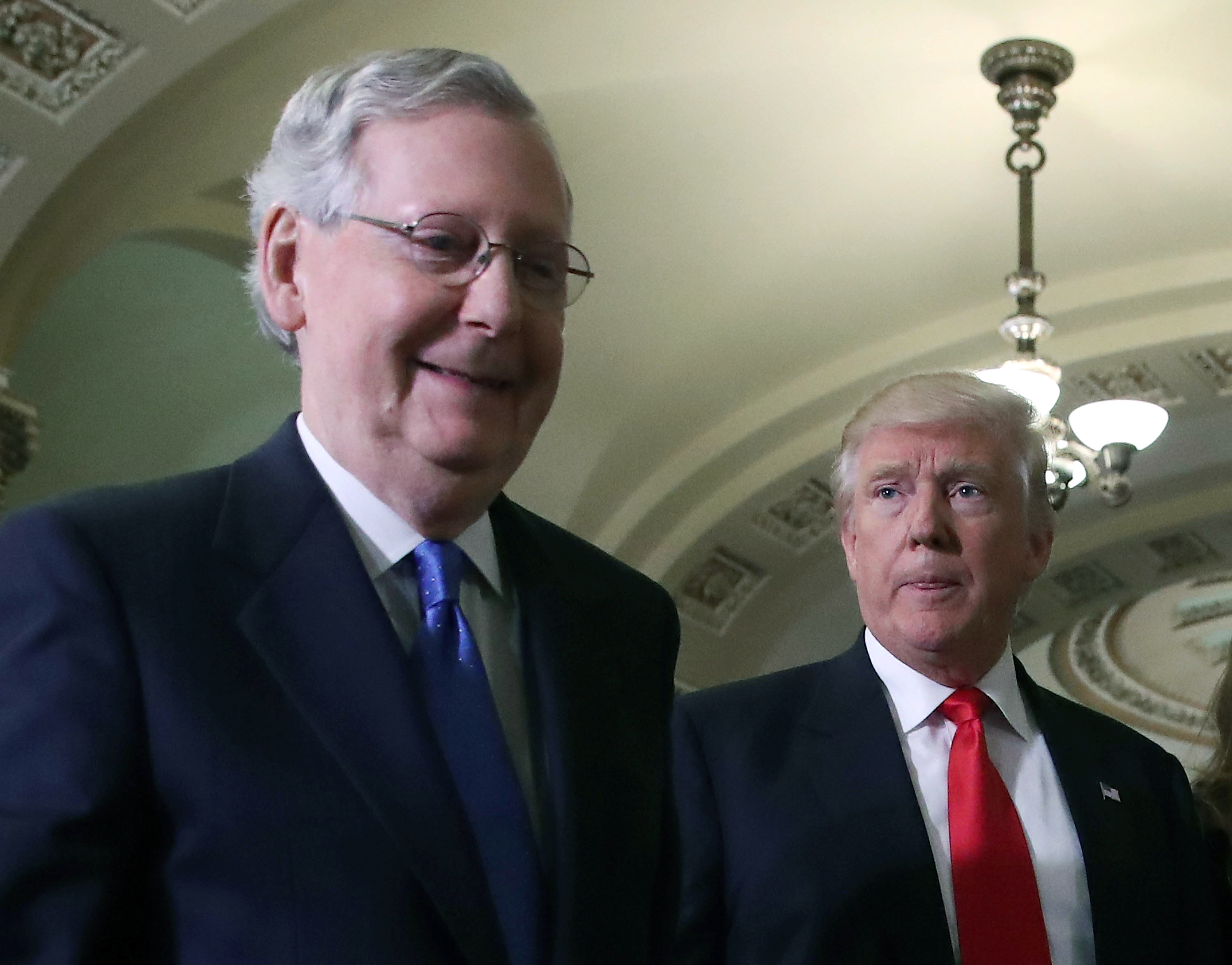

President Trump might want to run his ObamaCare backup plan by Mitch McConnell

He knows how blaming the minority party when you're in power works out

There are some people who believe that President Trump is a political genius. Despite never running for office before 2016, he won the White House through his impeccable instincts and deep insight, they say. But there are others who believe he benefited from good timing, a weakened Republican Party, an opponent weighed down by an antagonistic press and the unceasing efforts of the FBI director to destroy her, and some good old-fashioned luck, all of which allowed him to bumble his way into the Oval Office.

Now which interpretation of Trump would be suggested by this:

In an Oval Office meeting featuring leaders of conservative groups that are already lining up against House Republicans' plan to repeal and replace ObamaCare, President Donald Trump revealed his plan in the event the GOP effort doesn't succeed: Allow ObamaCare to fail and let Democrats take the blame, sources at the gathering told CNN. [CNN]

In a moment we'll address the politics of this strategy and whether it could actually succeed. But before we do, let's take a moment to consider the human consequences of what Trump is suggesting.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When he says he'll allow ObamaCare to fail, what he's saying is that his plan is to promote the maximum amount of suffering he can so that he'll have something to bash Democrats with. If he genuinely believes that the law is the hellish nightmare he and Republicans keep saying it is, that means he's willing to subject Americans to even more of its tortures while he reaps the political benefit.

As it happens, the Affordable Care Act has some issues that ought to be addressed, but on the whole it's working quite well, so Trump's plan would be a great service to the tens of millions of Americans who would be able to keep their insurance and the health security they now enjoy.

Now let's consider this as a political strategy.

Trump's apparent belief is that even though Republicans control the White House and Congress, the power of his bully pulpit is so extraordinary that he can attribute the GOP's own failure to the opposition, and Americans will all accept what he says. But there's a simple truth of American politics he may not grasp: The party in power, and particularly the president, are responsible in the public's mind for pretty much everything that happens. Sometimes that means the president gets more credit or blame than he deserves. But trying to argue that it's the party with no power that bears responsibility for what's happening in the country almost never works.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Trump might want to ask Mitch McConnell how likely the wait-for-things-to-go-wrong-and-blame-the-Democrats strategy is to succeed. When Barack Obama was elected, McConnell realized that gumming up the gears of government might subject the opposition to some strongly-worded editorials, but the subtleties of who was to blame wouldn't really register with the public. All they'd see was that "Washington" couldn't get anything done, and they'd blame the president's party. Which is why Republicans could execute a strategy of unending obstruction throughout Obama's presidency and be rewarded with two huge midterm election wins that gave them back control of Congress.

I suspect that Trump is working off a fundamentally inaccurate logic here, one that goes like this: "People believe whatever I tell them. ObamaCare is the Democrats' law. If I tell them whatever they don't like about health care is the Democrats' fault, they'll buy it."

The first problem is that only Trump's supporters believe whatever he tells them — and they're a minority of the country. The second problem is that he's the president now, and he's responsible for everything. Just as Obama got blamed for weaknesses in the American health system that predated the ACA (like insurers limiting provider networks to cut costs, a trend that started years ago), Trump will be blamed for whatever he and the Republicans haven't fixed.

He and his party are facing a Catch-22, whether they know it or not: If they succeed in passing their plan, they'll get blamed for the catastrophic consequences that will ensue (millions losing coverage, increased costs for others, the potential collapse of the individual market), but if they don't pass their plan, the GOP base, which has been promised repeal of the ACA for seven years, will be enraged. Pass it and Democratic voters will flock to the polls in 2018 to punish them; fail to pass it and Republican voters will stay home in disgust.

So Trump is considering the old Marxist tactic of "heightening the contradictions," where you make the situation so bad that the public turns to you to save them. But it doesn't work when you're the one in power.

That may be why the Trump administration is telling people not to refer to the Republican bill as "TrumpCare." It's almost as if they know it's a turkey, and don't want to be too closely associated with it.

Paul Waldman is a senior writer with The American Prospect magazine and a blogger for The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in dozens of newspapers, magazines, and web sites, and he is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics.

-

7 bars with comforting cocktails and great hospitality

7 bars with comforting cocktails and great hospitalitythe week recommends Winter is a fine time for going out and drinking up

-

7 recipes that meet you wherever you are during winter

7 recipes that meet you wherever you are during winterthe week recommends Low-key January and decadent holiday eating are all accounted for

-

Nine best TV shows of the year

Nine best TV shows of the yearThe Week Recommends From Adolescence to Amandaland

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook