Why the Republican health-care effort is heading for disaster

To paraphrase President Trump, who knew governing could be so complicated?

If all goes according to plan — never a sure thing with today's GOP — the House of Representatives will vote some time Thursday on its plan to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act. This bill has been a fiasco from the beginning: Hastily assembled despite the seven years Republicans had to prepare for this moment, judged by the Congressional Budget Office to potentially throw 24 million people off their coverage, and reviled by conservatives, moderates, and liberals, it has been a legislative disaster of the kind one seldom gets the opportunity to witness. "While I've been in Congress," said Republican Rep. Justin Amash, "I can't recall a more universally detested piece of legislation than this GOP health-care bill."

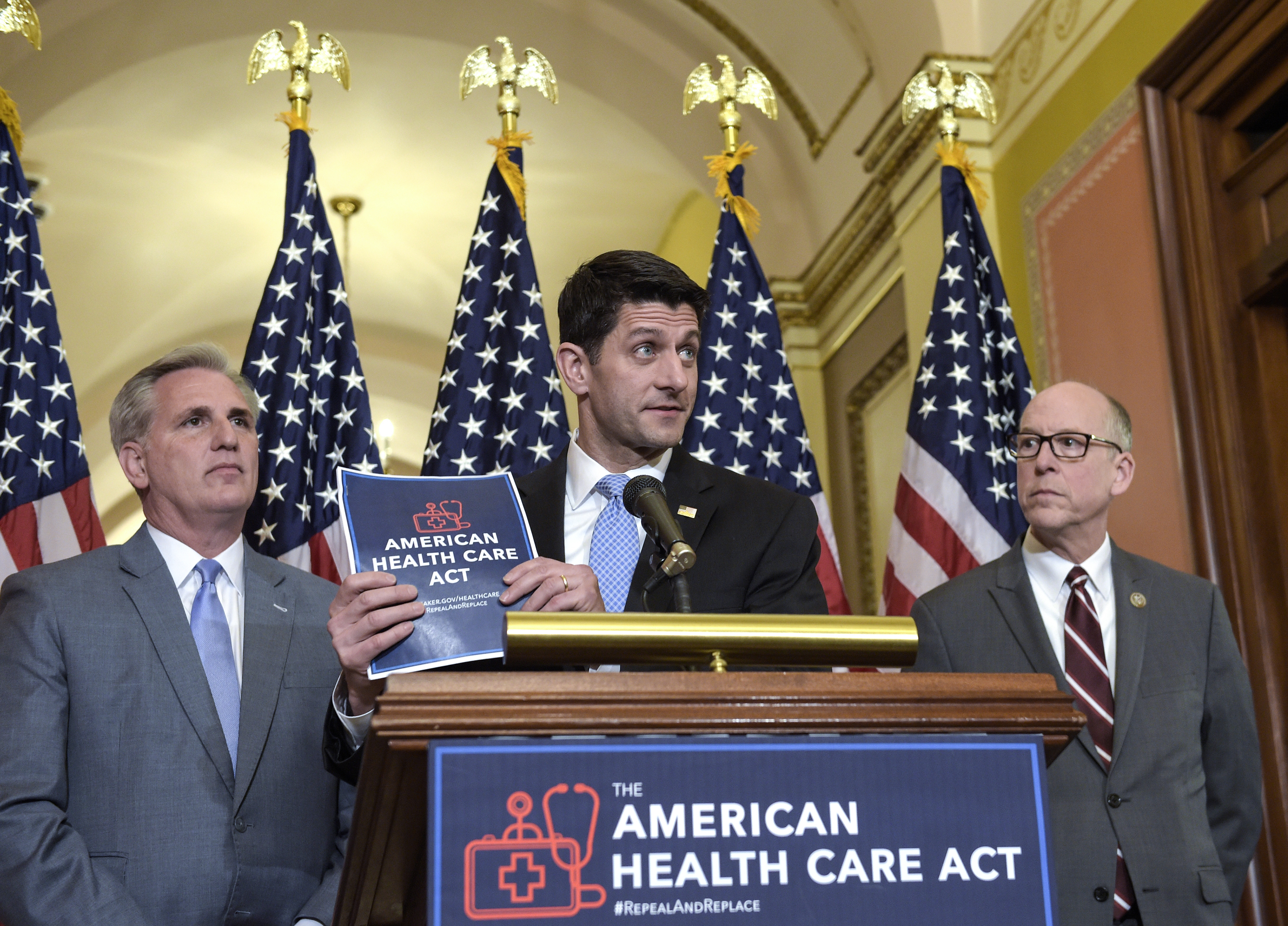

As the time of the vote has approached, Speaker of the House Paul Ryan and President Trump have been working hard to yank this enormous turd of a bill across the 218-vote threshold it needs to pass. Trump, his popularity down in the 30s and his administration mired in scandal, took to threatening House Republicans. "I'm gonna come after you" if you don't support the bill, he said to Mark Meadows, head of the ultra-right House Freedom Caucus, whose members have put up the staunchest resistance. This master negotiator didn't take the time to figure out that Meadows and his comrades are never happier than when they're making a principled stand against powerful forces; Trump probably made their opposition even more likely.

Meanwhile, Ryan was busy adding provisions of the bill to please various members, like a gift to members from upstate New York who wanted to change the way Medicaid is funded in their state (The Binghamton Bribe? The Plattsburgh Payola? The Cooperstown Kickback?), or a vaguely defined fund that might ease the way the bill screws over older patients. But none of it solves the basic vote-counting problem, which is that any bill that's cruel enough to pass through the House can't pass the Senate (where Republicans can afford to lose only two votes), and any bill that's generous enough to pass the Senate can't pass the House.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

By now it should be clear that many Republicans wish this whole thing would just go away so they can move on to the thing that really excites them: cutting taxes. If the bill should somehow manage to pass the House, the plan in the Senate is to bring it to a vote as quickly as possible. Its prospects are dim, but could be even worse if it were allowed to hang around getting debated for a while. "We'll either pass something that will achieve a goal that we've been working on," says Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, "Or not."

That is not the sound of a man brimming with optimism — or of a man who thinks the world will end if this bill fails — and if there's one thing McConnell knows, it's how to count votes. So while the prevailing assumption for months has been that Republicans have no choice but to pass some version of repeal given the promises they've made over the last seven years, failure is suddenly looking like not just an option, but maybe the best option.

The recent debate has made clear to Republicans not only that they are faced with nothing but bad choices, but that repealing and replacing the ACA may be the worst one. The news has been filled with warning signs — about the millions who would lose coverage under any plan they could agree on, about the Trump voters who are suddenly terrified that they could lose their coverage, about the chaos that their plan would throw the insurance market into — and breaking their promise to snuff out the ACA may be the only way to survive.

It would be a tremendous failure, without doubt. But there is a path they could follow from there. Republicans could say, "We tried to do it quickly and all at once, but there were too many differences among us. So now we're going to attack it piece by piece." They could then start introducing more limited bills to make conservative changes to the law — a repeal of the individual mandate here, a tax break for health savings accounts there, some cutbacks to Medicaid over there — and assure their constituents that they're still on the case. It's not a perfect solution, but it may be the only one they've got.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And then they could get to the fun stuff: cutting taxes for the wealthy, eviscerating environmental regulations, slashing wimpy programs like food stamps and medical research. A couple of them might have to endure primary challenges from the right because they didn't send the ACA straight to hell. But they know that the more immediate danger comes in the form of a "wave" election in 2018, in which energized Democrats and disgusted independents would flock to the polls to kick out their sitting representatives.

But no matter how they decide to handle it, this has not exactly been an auspicious beginning to our glorious new era of Republican rule in Washington. To paraphrase President Trump, who knew governing could be so complicated?

Paul Waldman is a senior writer with The American Prospect magazine and a blogger for The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in dozens of newspapers, magazines, and web sites, and he is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics.

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook