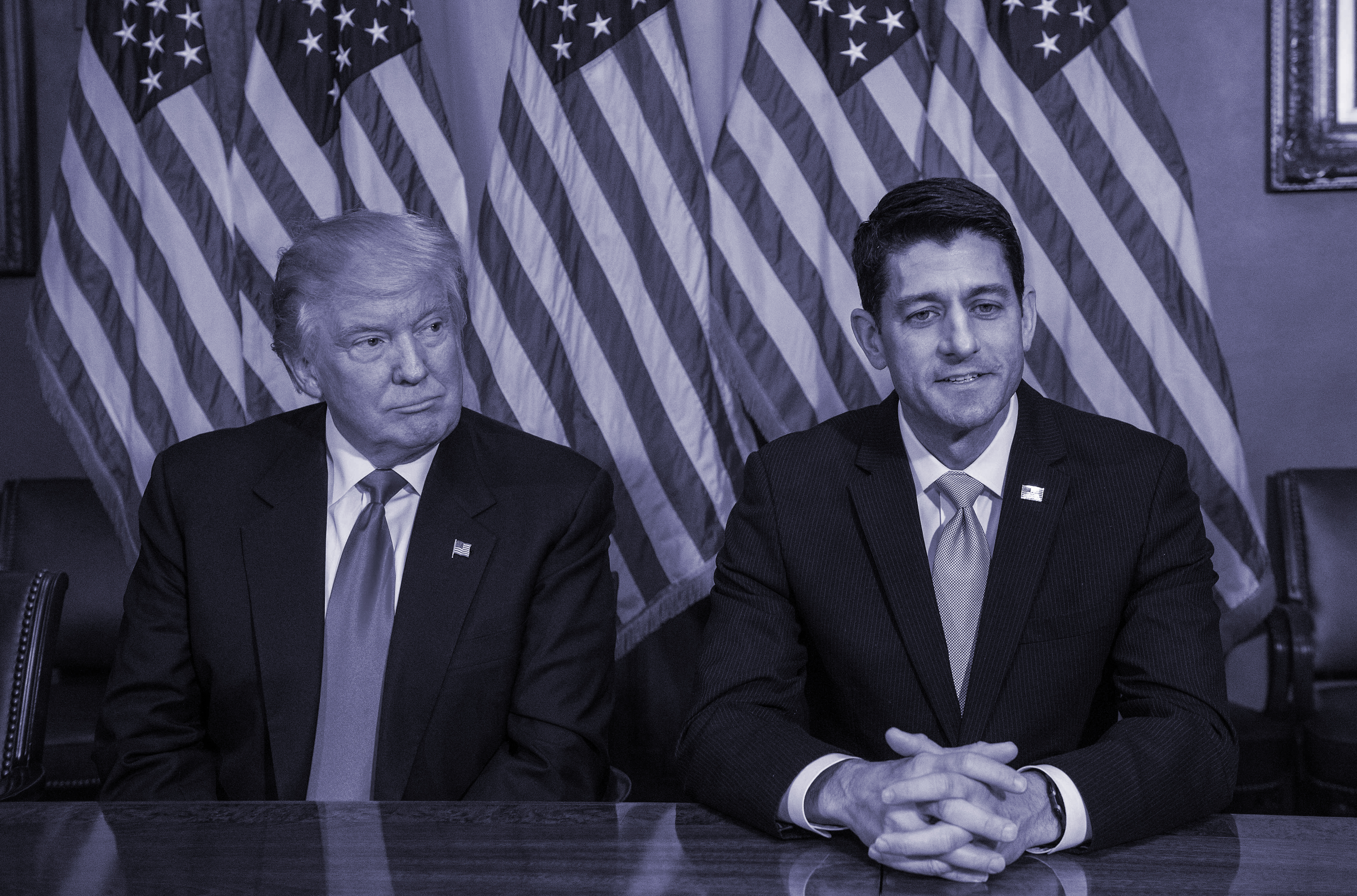

So how is the Trump era working out for Paul Ryan?

Let's check in

This was supposed to be a time of joy and progress for the Republican Party's golden boy, Paul Ryan. In 2015 he reluctantly accepted the position of speaker of the House, at last hearing the desperate pleas of his colleagues to lead them in a troubled time. The deep policy knowledge for which he was so often praised by Washington reporters, combined with his ultra-ripped biceps and delts, would guide them through the political minefields they had lain for themselves. And when Donald Trump became his party's nominee, Ryan expressed his principled misgivings in a tone of perfectly attuned concern and sorrow, repeatedly telling voters that he could not abide the latest despicable thing Trump said (but by the way, please vote for him).

Then when Trump won a surprise victory, all the waiting and fighting and angst was supposed to be redeemed in a glorious eruption of conservative legislation. With a Republican in the White House who neither knew nor cared about policy at all, it would be left to Ryan to remake America according to his vision of a Randian paradise where society's makers are duly rewarded, and the bleating masses either get themselves a strong pair of bootstraps or learn what life is like without a government "hammock" to support them.

But 100 days in, things aren't looking quite so glorious. In fact, not only has no legislation of consequence been passed, Ryan is looking like such a screwup that his own political future is in doubt. He seems to remain speaker only because no one else wants the job, and no one is talking about him being president one day the way they used to. A recent Pew Research Center poll put Ryan's approval rating at 29 percent, with 54 percent disapproving — worse than John Boehner, Nancy Pelosi, or Newt Gingrich scored at this point in their respective speakerships.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Ryan might complain that he is beset by an angry right flank that never trusted him, which is true. The arch-conservatives of the House Freedom Caucus continue to make trouble, resentment still burns among those who felt Ryan was insufficiently supportive of Trump during the campaign, and Breitbart News, which speaks to the right in the voice of its former chief Stephen Bannon, continues to pummel him, as does the Drudge Report.

But after the debacle of the effort to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act, the White House doesn't trust him anymore either. According to a recent report in Politico, "Several administration officials said Trump has told them not to leave the congressional details [of legislation] to Ryan and others."

Quite the debacle it was — and blame for it has to lie at Ryan's feet. The surprise wasn't that Republicans were unable to come up with a plan that would be cruel enough to satisfy their most conservative members yet not produce a political disaster. The surprise was that they, and Ryan in particular, were so unprepared. The alleged policy wizard sitting in the speaker's chair had seven years to devise an alternative to the Affordable Care Act, but he never got around to it. If he had, he might have been able to spend some time building support for it, improving it, determining how it would be received by the public and key stakeholders like hospitals, insurers, doctors, and patient advocates. But he did none of that.

Instead, in a matter of a few weeks he cobbled together a plan that was so repulsive to so many people that one wonders how the whole thing could have gone any worse. Democrats were united and mobilized against it, the Congressional Budget Office declared that it would lead 24 million Americans to lose their health coverage, all the stakeholders came out against it, and both moderates and conservatives in Ryan's caucus hated it (albeit for different reasons). Ryan couldn't convince his own members to support it, and neither could the White House; it was withdrawn before ever coming to a vote.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And now they have a new version, which manages to be even more awful than the first one. Among other things, it takes what may be the most popular part of the ACA — its ban on insurers denying coverage to those with pre-existing conditions — and guts it, in order to get the support of those Freedom Caucus members who were disappointed that the last bill wasn't even more heartless. This one too seems guaranteed to fail — if it somehow passes the House, it will almost surely die in the Senate.

The president will get some of the blame when the repeal effort finally dies, but much will also fall on Ryan, and justifiably so. He was supposed to be the one who would provide the substantive ballast for this new era of Republican rule — Trump would go out and Make America Great Again, while Ryan would craft and pass the laws required to put conservatism into action. But he can't seem to get it done.

There's still time, though. Ryan will have at least until the end of 2018, or 2020 if Republicans can avoid a midterm sweep. But it turns out that Trump isn't the only one learning that this governing stuff is harder than it looks.

Paul Waldman is a senior writer with The American Prospect magazine and a blogger for The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in dozens of newspapers, magazines, and web sites, and he is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics.

-

Why are federal and local authorities feuding over investigating ICE?

Why are federal and local authorities feuding over investigating ICE?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Minneapolis has become ground zero for a growing battle over jurisdictional authority

-

‘Even those in the United States legally are targets’

‘Even those in the United States legally are targets’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Magazine printables - January 16, 2026

Magazine printables - January 16, 2026Puzzle and Quizzes Magazine printables - January 16, 2026

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred