Will China own the future of AI?

At this rate, maybe ...

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the 1982 film Firefox, Clint Eastwood plays an Air Force pilot and Vietnam vet on a secret mission to steal an advanced Soviet fighter jet. The airplane is super fast, radar invisible, and can be controlled by thought (as long as those thoughts are in Russian). "Yeah, I can fly it," Eastwood says. "I'm the best there is."

Two year later, Tom Clancy published The Hunt for Red October, later made into a film starring Alec Baldwin and Sean Connery. In this thriller, the revolutionary piece of Soviet technology is a super quiet nuclear submarine, almost undetectable by sonar.

Both pieces are fascinating Cold War artifacts playing off fears that the Soviet Union would manage a military version of Sputnik, leapfrogging U.S. tech and giving Moscow the decisive upper hand against the West. In reality, of course, the opposite was happening.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What if these two films were, as Hollywood puts it, "reimagined" for today's audiences? The tech MacGuffin would likely be Chinese artificial intelligence. Imagine Jason Bourne sneaking into China to download super intelligent software that would make that country's military and economy dominant. Or maybe he would kidnap a key Chinese computer scientist and bring him back stateside for interrogation.

Such a film would have an obvious "ripped from the headlines" feel about it. Specifically, headlines like this one from last weekend's New York Times: "Is China outsmarting America in AI?" Reporters John Mozur and John Markoff declare the "balance of power in technology is shifting" with China perhaps "only a step behind the United States" in artificial intelligence.

And as Beijing readies new multibillion dollar research initiatives, what is America doing? "China is spending more just as the United States cuts back," the Times journalists write. Indeed, the new Trump administration budget proposal would sharply reduce funding for U.S. government agencies responsible for federal AI research. For instance, the pieces notes, budget cuts could potentially reduce the National Science Foundation's spending on "intelligent systems" by 10 percent, to about $175 million.

It is unlikely that Congress would ever pass a budget with such draconian cuts, especially since wonks and policymakers on the left and right see basic science research as a proper and necessary role for government. Then again, Washington hasn't really been acting like science is an important national priority. As a share of the federal budget, basic science research has declined by two-thirds since the 1960s.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

President Trump's proposed cuts are particularly striking since the just-departed Obama administration saw AI as critical technology with "incredible potential to help America stay on the cutting edge of innovation." Striking, but not surprising given that candidate Trump didn't even have a technology policy agenda. And what passed for an industrial strategy focused on reviving American steel manufacturing and coal mining. Perhaps America First doesn't really apply to science.

Of course, some conservative budgeteers advising the Trump White House argue that inefficient and speculative public investment "crowds out" private investment that is more likely to pay off in practical advances. But no one has apparently informed Eric Schmidt, executive chairman of Alphabet, the parent company of Google. The $700 billion tech giant, noted for its "moonshot" projects, is often held up an an example of how companies are where the really important research is done.

But in a recent Washington Post op-ed, Schmidt wrote that the "miracle machine" of American postwar innovation comes from the twin "interlocking engines" of the public and private sector. Without more public research investment, "we may wake up to find the next generation of technologies, industries, medicines, and armaments being pioneered elsewhere."

China is obviously far more capable of both invention and commercial application than the old Soviet Union. Its companies are already leaders in mobile tech. It's not hard to imagine why it would be better for U.S. workers to have America be the nation where the next generation of innovation is turned into amazing products and services. Plus, it would be odd for the world's leading military power not to also be the nation pushing the tech frontier. Certainly better us than an authoritarian nation that plans on using its advanced AI to enhance its ability to control its citizens, as well as enhance military capabilities.

America must spend more, maybe a lot more, on research. It should also do a better of job of attracting and keeping the world's best and brightest. Let's make sure this story has a happy ending.

James Pethokoukis is the DeWitt Wallace Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute where he runs the AEIdeas blog. He has also written for The New York Times, National Review, Commentary, The Weekly Standard, and other places.

-

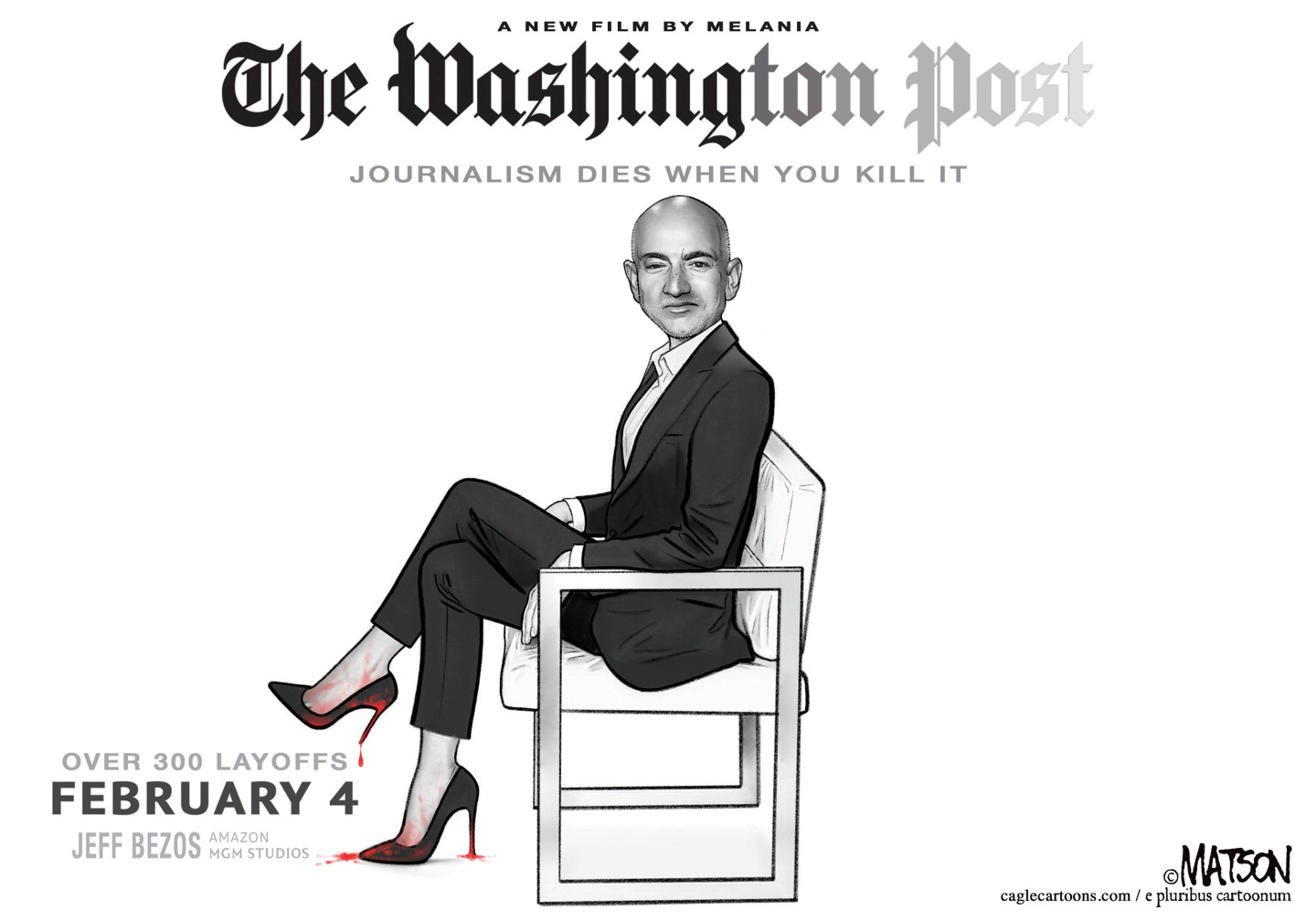

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred