Centrist Democrats need a compelling vision for America

What do neoliberals stand for?

It's easy to mock Democrats for their interminable squabbles.

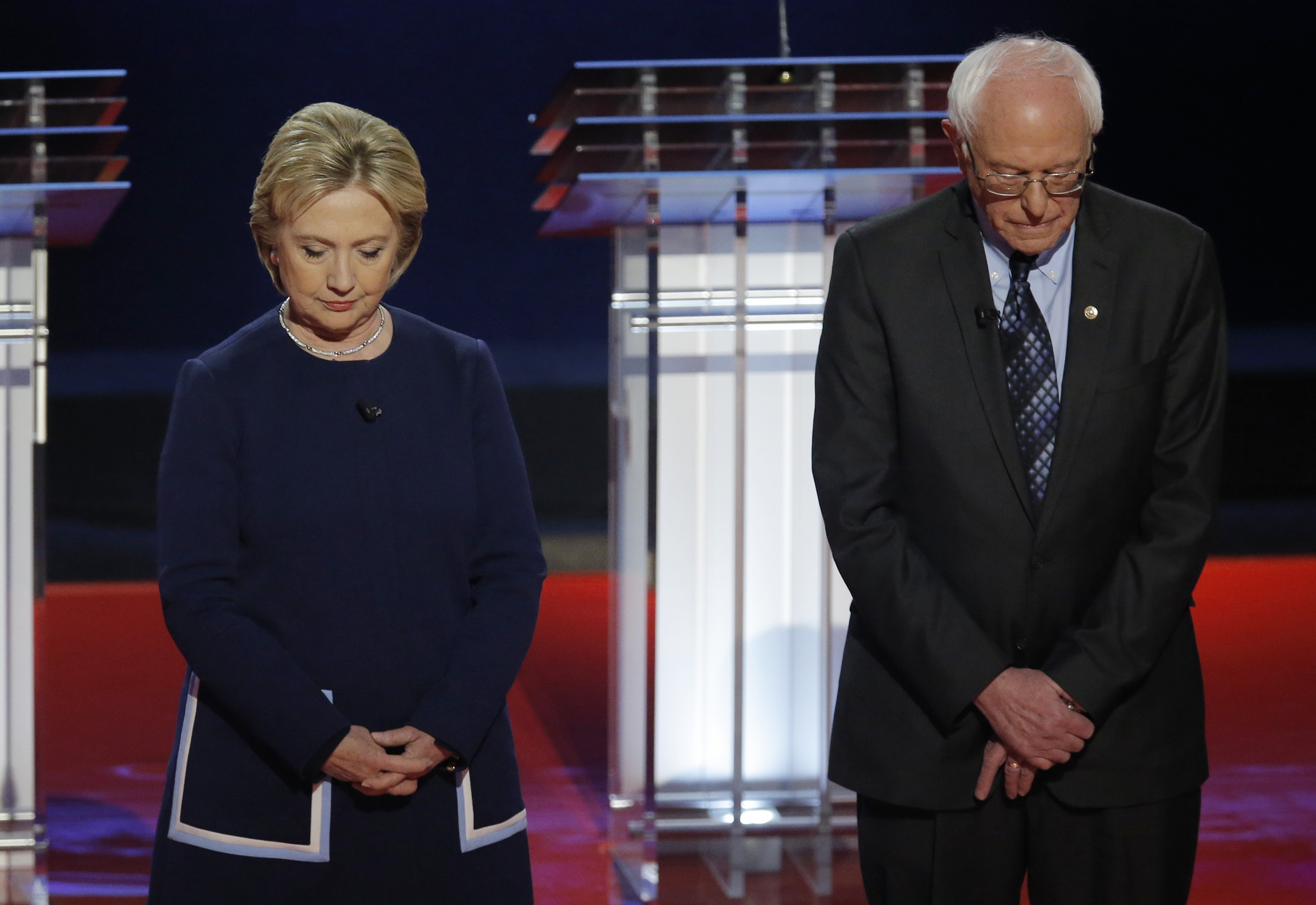

Here it is, a year past the end of the Democratic primary contest between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, and seven months after Clinton's shocking defeat at the hands of Donald Trump, and the Clinton and Sanders factions are still at each other's throats, fighting bitterly over the future direction of the party.

Over the past week, these tensions have risen once again to a rolling boil, provoked by the surprisingly strong showing in the U.K.'s snap election by Jeremy Corbyn's newly left-wing Labour Party, and the even more impressive first-round election results by the new-fangled and proudly neoliberal party of French President Emmanuel Macron. The first seems to confirm the Sanders faction in its conviction that turning the Democratic Party sharply to the left will bring electoral success, while the second supposedly points to the enduring strength of a centrist governing agenda. (Both factions can be seen duking it out on the front page of Monday's New York Times in a story clearly written out of sympathy for the neoliberal side of the argument.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Regardless of whether it makes sense in any particular race for the Democratic candidate to hug the center or bolt to the populist-socialist left, there is one thing that the Sanders faction unquestionably does much better than its neoliberal counterparts — and that is to stand confidently for what it believes and make the case for it in terms of the good of the country.

The centrists for the most part don't do this. Instead, they act and speak like people who've spent too much time in meetings with political consultants, professional strategists, pollsters, and data crunchers. There's nothing wrong with the people who do this work, and all candidates (including Sanders) employ them. But a political party and its leading candidates should never defer to the consultants and strategists when it comes to deciding what their core message should be.

Do the Democrats want to continue embracing neoliberalism? Then its candidates should make the case for those policies forthrightly and without apology, explaining to voters in an inspiring way why they are best for the country and its people. What the party should not do is continue to propose neoliberal policies because it thinks that's the best Democrats can hope for given constraints imposed by Republicans.

The habit of Democrats playing politics within the boundaries set by their electoral opponents dates back to the 1980s, when Ronald Reagan succeeded in enacting an electoral realignment, in the process shifting the American political spectrum several clicks to the right. After losing the fight over that shift in 1984 and 1988, Democrats helped to consolidate it by nominating an unabashed neoliberal in 1992 who went on to win narrowly after promising to move in the direction of the GOP on trade, crime, welfare policy, and other issues.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Bill Clinton's presidency got off to a rough start after he took more traditionally liberal positions on gays in the military and health-care reform. But after the rebuke of the 1994 midterm elections, he tracked back to the center and governed from there for the remainder of his presidency, leaving office with an approval rating of 66 percent.

Whether Clinton truly believed in his neoliberalism was beside the point. He was a politician of such rare skills that it didn't matter: He sounded like he believed it, and was uncommonly good at making the public case for it. Others, like Al Gore and John Kerry, were not so gifted.

Barack Obama rivaled Bill Clinton for charisma on the campaign trail, but he used his talents to fudge matters. Talking like the inspirational community organizer he once was, Obama sounded like he was leading a revolution, and even spoke contemptuously about the expedient compromises of the Clinton era. But in the end the slogans were vacuous (Yes we can! Change we can believe in!) — and when it came to governing, Obama's instincts were as moderate and conciliatory as any neoliberal's, especially in the face of the Tea Party onslaught from the right.

I can't be the only observer of the 2016 presidential campaign who assumed Hillary Clinton would have loved to run for president championing Bernie Sanders' agenda. All those primary debates in which she played the part of the sober, realistic, experienced manager throwing cold water on the fiery indignation and heady pipe dreams of the socialist agitator — it must have been excruciating. Or maybe the real Clinton was the woman who confessed to an audience of bankers her neoliberal dream of a hemisphere-wide free-trade and open-border zone. In that case, the confrontation with Sanders would have been excruciating in a different way, like the struggles of an exhausted parent forced to contend with the overactive imagination of an immature child.

Which was it? Hell if I know. And that's the problem.

Instead of giving a passionate, lyrical speech in which she publicly defended that dream of free trade and open borders — or going in the other direction and confidently co-opting Sanders' socialist agenda — Clinton spent the bulk of her time mocking Donald Trump and directing voters to her website, where they found dozens of little policy proposals, each scrupulously focus-group tested and micro-targeted at a different segment of the electorate.

Those consultants no doubt believed that if you added up all of those segments Clinton would easily prevail on Election Day. They forgot just one thing: that her policy proposals needed to be embedded in an overarching story about America, including a vision of the country's future to which those policies would make a crucially important contribution.

Sanders told such a story about his own proposals — about how they would address the rise of inequality and the struggles of our fellow citizens, and how they would prevent rapacious bankers from continuing to enrich themselves at the expense of ordinary, hard-working Americans.

Trump told his own, very different story — about the need to make America great again and about how the country's vitality had been sapped by both the self-dealing corruption and incompetence of the nation's political establishment and by the criminality and terrorism of undocumented immigrants.

What was Clinton's story? That it was time for a woman to be president? That it was her turn? That Americans should elect a competent manager to preside over the federal government as it drifts aimlessly onward, slowly, gradually expanding over time?

That the Democrats managed to win the popular vote and narrowly lose the Electoral College despite the vacuousness of this message is a testament to just how repulsive many people found the Republican nominee, and just how many people are willing to support the country's left-of-center party no matter what its standard-bearer says (or doesn't say).

This doesn't mean the answer to the Democratic Party's woes is a leftward lurch. But it does mean that wherever the party decides to plant itself ideologically, it should do so because it believes that's what will most benefit the country and its people — and because it can make a compelling and convincing case in favor of that decision.

That's when they should bring in the consultants. But not one moment sooner.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

What will the US economy look like in 2026?

What will the US economy look like in 2026?Today’s Big Question Wall Street is bullish, but uncertain

-

Alaa Abd el-Fattah: should Egyptian dissident be stripped of UK citizenship?

Alaa Abd el-Fattah: should Egyptian dissident be stripped of UK citizenship?Today's Big Question Resurfaced social media posts appear to show the democracy activist calling for the killing of Zionists and police

-

Biggest political break-ups and make-ups of 2025

Biggest political break-ups and make-ups of 2025The Explainer From Trump and Musk to the UK and the EU, Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without a round-up of the year’s relationship drama

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook