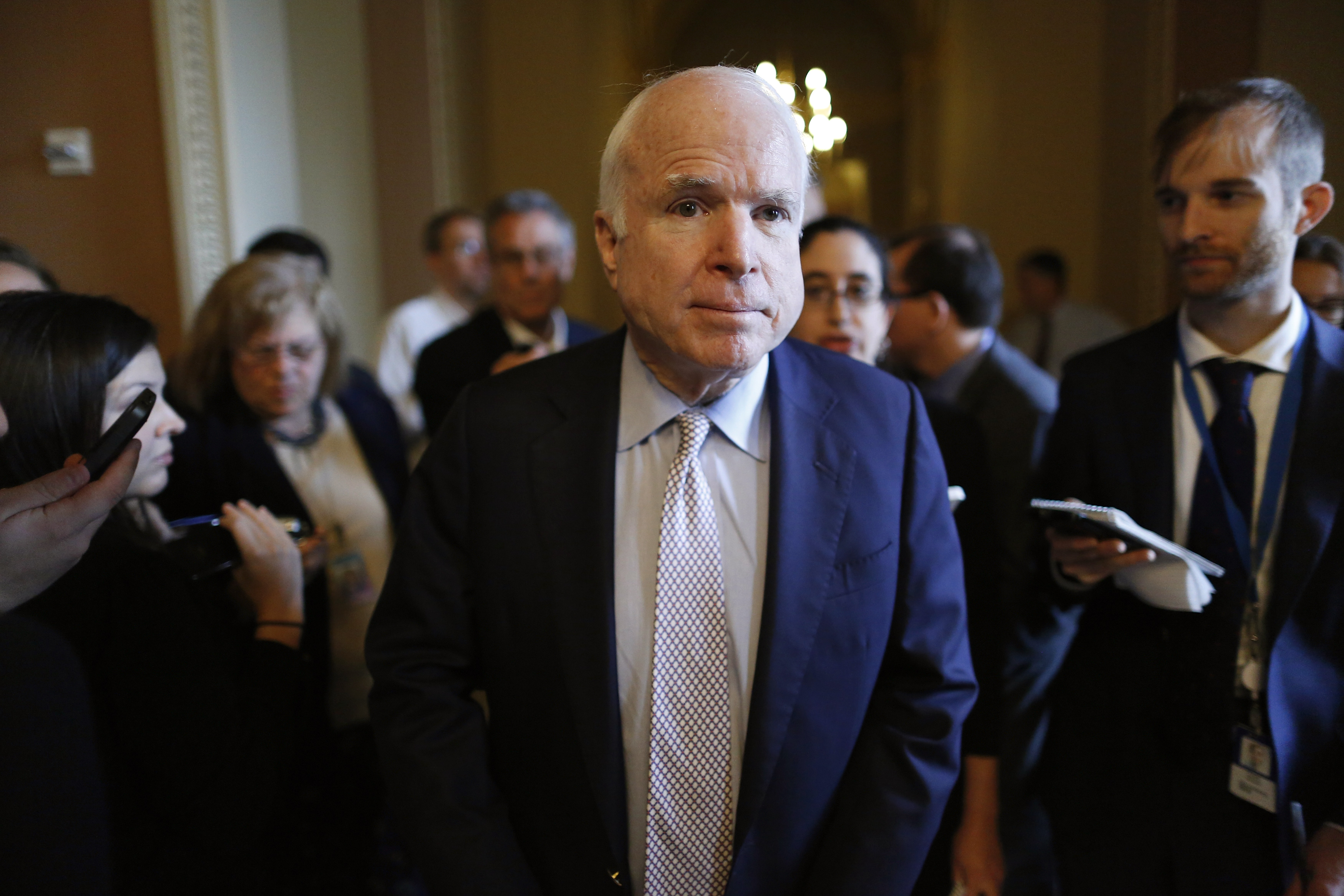

McCain the fraud

Here's what John McCain has actually done since that stirring speech about Senate bipartisanship

John McCain, recently diagnosed with an aggressive form of brain cancer, returned to Washington this week to a rapturous welcome. But it's what he did afterward that is so remarkable. And it's only appropriate that his actions on the health-care bill Republicans are squeezing through the Senate will be perhaps McCain's final act as a politician, because it has all the hallmarks of his career: He's being excused from the skepticism other politicians receive while lauded for virtues he isn't demonstrating.

A brief summary of what has happened as of this writing: McCain came to the Senate and cast a "yes" vote on the motion to proceed, allowing debate to begin on ... something, but no one knew exactly what. There was not a bill to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act on offer, but a bunch of bills that might or might not be voted on in the ensuing days. There has not been a single hearing on these bills, no regular committee process, and no opportunity for more than a handful of Republican senators — let alone Democrats — to have any input into what they'd be voting on. Republicans needed McCain's vote, because two of their members voted no, and they have only a 52-seat majority (Vice President Pence broke the 50-50 tie).

With his stamp of approval on this atrocious twisting of the legislative process, McCain then went to the Senate floor to deliver a stirring tribute to the traditions of the body, and a rebuke to their degradation in recent years:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Let's trust each other. Let's return to regular order. We've been spinning our wheels on too many important issues because we keep trying to find a way to win without help from across the aisle. That's an approach that's been employed by both sides, mandating legislation from the top down, without any support from the other side, with all the parliamentary maneuvers that requires…We've tried to do this by coming up with a proposal behind closed doors in consultation with the administration, then springing it on skeptical members, trying to convince them it's better than nothing, asking us to swallow our doubts and force it past a unified opposition. I don't think that is going to work in the end. And it probably shouldn't. [McCain]

Yes, McCain pled for a return to regular order, right after voting to push through the GOP health bill without anything like regular order. And then, just six hours later, he was offered an opportunity to vote on the first version of the GOP health bill, which just as he described, was crafted behind closed doors and sprung on the members in an attempt to force it past a unified opposition. What did he do? He voted yes.

For this bit of naked hypocrisy, McCain was hailed with all the poetic language journalists could muster. "In a Washington moment for the ages, Sen. John McCain claimed the role of an aging lion to try to save the Senate, composing a moving political aria for the chamber and the country that he loves," rhapsodized CNN. "The maverick stood with his party on Tuesday, casting a crucial vote in the Republican drive to repeal 'ObamaCare.' But then, like an angry prophet, Sen. John McCain condemned the tribal politics besetting the nation," said The Associated Press.

For those of us who have followed McCain's unique relationship with the news media, it was not at all surprising. He has long been held up as Washington's One Virtuous Man, despite the copious evidence to the contrary. On the rare occasions when he breaks with his party — always, it must be noted, when his party is taking an unpopular position, and so doing so puts him on the right side of public opinion — he wins plaudits for his independent spirit and strength of character, unlike others who do the same thing. They're just "moderates," but he's a "maverick," a cowboy riding out of the West with his six-guns loaded full of truth.

That image didn't come from nowhere. It was built, carefully and systematically, by McCain and a couple of key aides — and with the enthusiastic help of reporters who admired him and enjoyed his company. One of the things he realized early in his career was that reporters hate the fact that most politicians are so careful and practiced around them, so if you let loose with them — swore, joked, told ribald stories, and generally made friends — there could be enormous benefits. Among other things, they'd feel like they had access to the "real" McCain, and so they wouldn't be as eager to find fault with the public persona.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

So reporters became McCain's greatest advocates, testifying constantly to his status as a "maverick" (a word you'll find in literally thousands of stories about him over the years) and to his limitless virtue and good intentions. The jaded press might view other politicians as cynical manipulators, but McCain alone is seen as having only the purest of motives, no matter what he's actually doing.

And what is he doing now? Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski, one of two Republicans who voted against the motion to proceed on Tuesday, said that afterward, McCain told her, "You did the right thing." If that's true, why wasn't he able to do the right thing himself?

And then came a vote on a Democratic amendment to slow down this absurd process and send the bill through Senate committees, where it can be examined, debated, and discussed, where expert testimony can be heard, where amendments can be offered, and after which the public might get a clearer idea of what it would do. This is exactly what McCain asked for in his Tuesday speech. And how did he vote? He voted no.

Let me be clear about one thing. John McCain has a dire diagnosis; people with glioblastoma don't usually live very long, particularly at his age. That is a very sad thing, and like everyone else I feel bad for him and his loved ones. But McCain is a public figure and an important politician, so what matters most to me is the contributions he has made to public life and public policy. If you put yourself in the arena, people will judge you by your actions there, and you shouldn't expect a pass when you become ill.

I doubt McCain does expect that. But just as he probably knew would happen, upon his return to Washington he was showered with praise and held up as an example of the nobility and integrity to which all politicians should aspire, just as he was voting like a crass partisan to take away health coverage from tens of millions of Americans, and doing it while offering sanctimony about the lost tradition of bipartisan comity in the Senate.

Forgive me for finding it less than inspiring.

Paul Waldman is a senior writer with The American Prospect magazine and a blogger for The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in dozens of newspapers, magazines, and web sites, and he is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics.

-

Political cartoons for December 13

Political cartoons for December 13Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include saving healthcare, the affordability crisis, and more

-

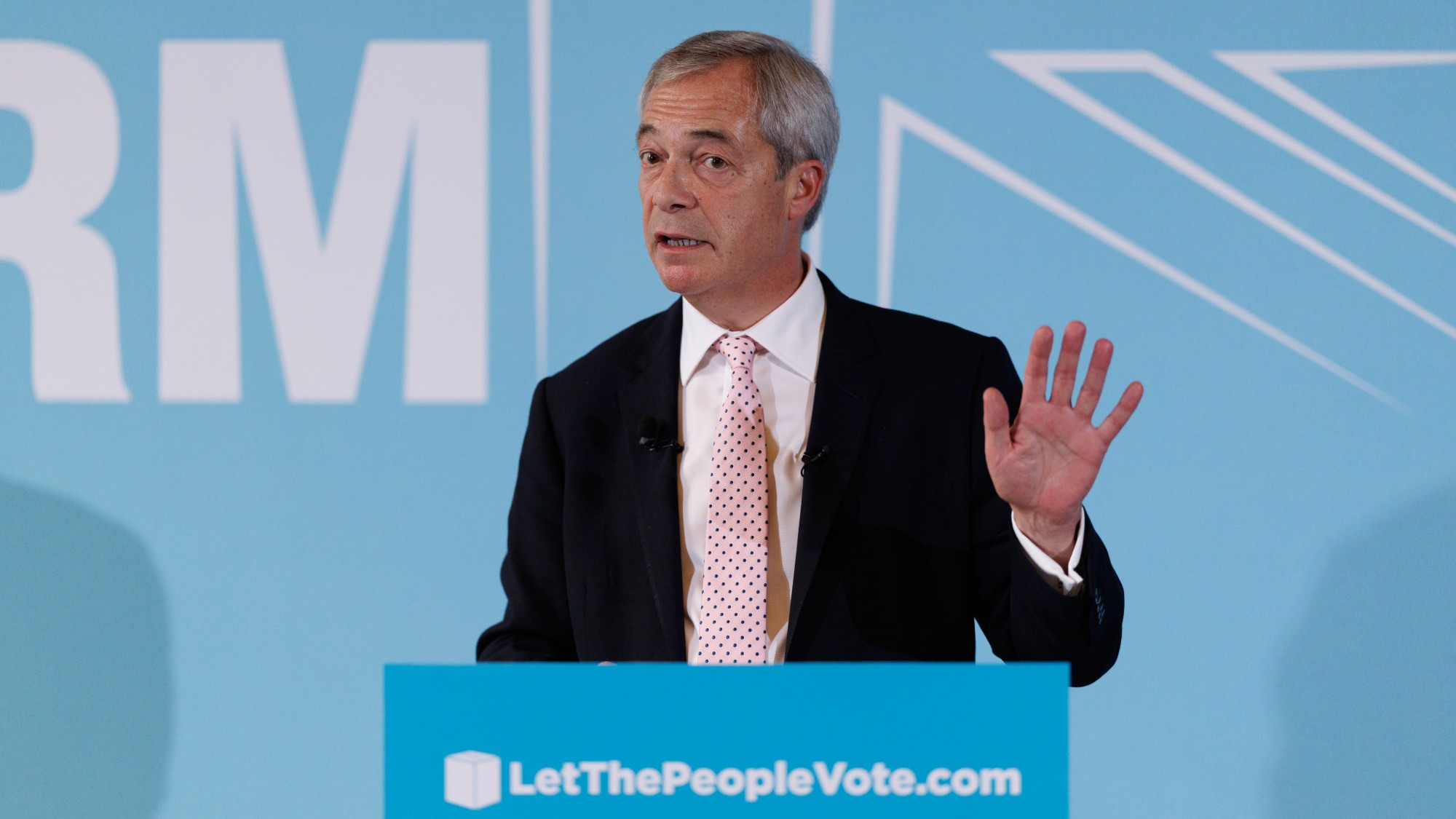

Farage’s £9m windfall: will it smooth his path to power?

Farage’s £9m windfall: will it smooth his path to power?In Depth The record donation has come amidst rumours of collaboration with the Conservatives and allegations of racism in Farage's school days

-

The issue dividing Israel: ultra-Orthodox draft dodgers

The issue dividing Israel: ultra-Orthodox draft dodgersIn the Spotlight A new bill has solidified the community’s ‘draft evasion’ stance, with this issue becoming the country’s ‘greatest internal security threat’

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration