How Democrats can get a clue on foreign policy

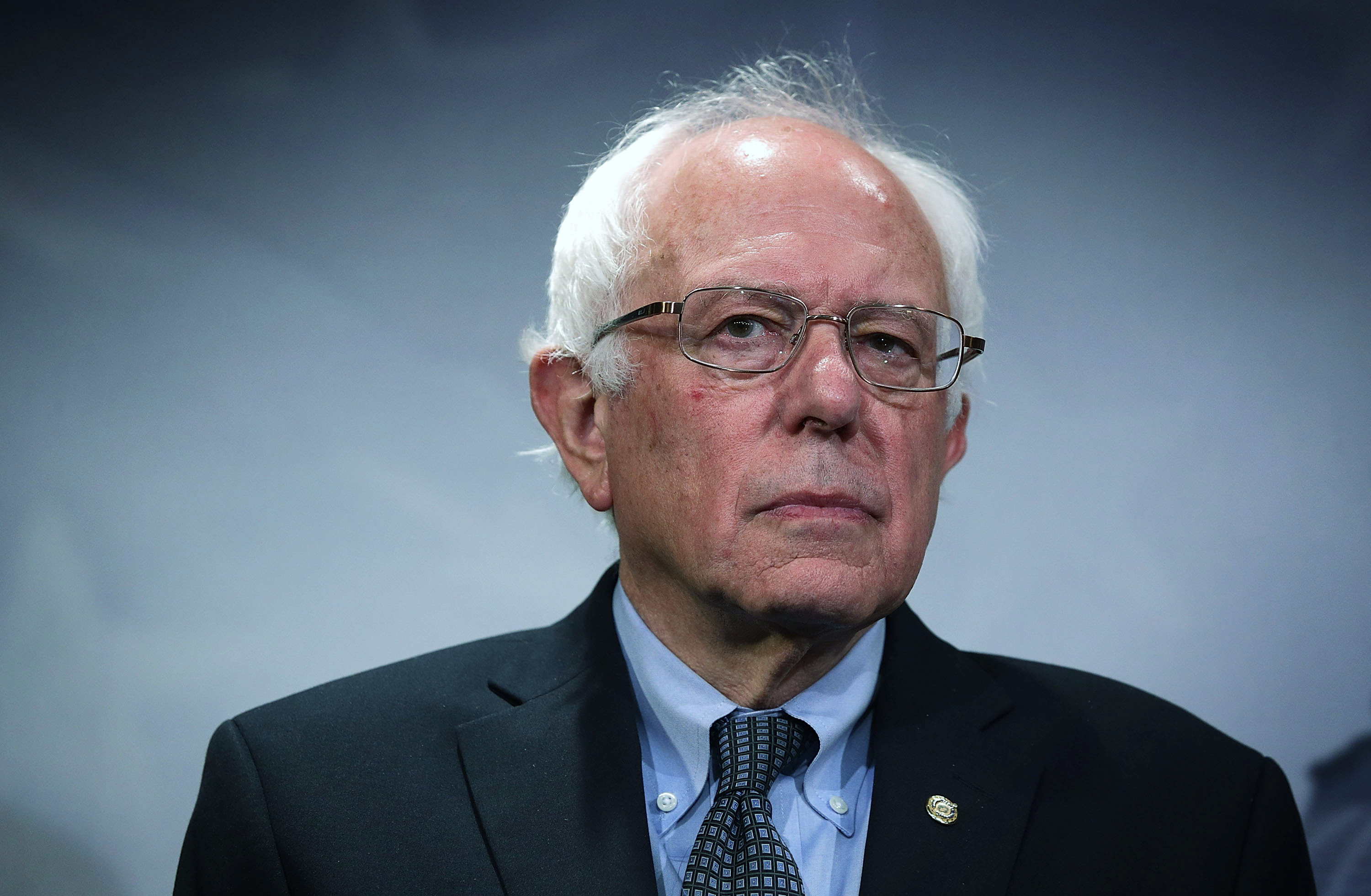

Listen to Bernie Sanders

How should America behave in the world? That question continues to confound the Democratic Party. Months into the Trump administration's increasingly unhinged confrontations with North Korea, party grandees have little to offer but tepid criticism — while voting overwhelmingly for large increases in military appropriations.

But there are signs that some in the party at least are beginning to get a clue. In a major speech at Westminster College, Bernie Sanders outlined a vision of foreign policy that would address the failures of recent history while providing a path for America to use its power honorably.

Many have forgotten this, but in the 2008 Democratic presidential primary, the main axis of debate was foreign policy. Hillary Clinton argued that her longer experience made her more qualified, while Barack Obama — who had at that point only been a senator for less than four years — argued that her vote for the Iraq invasion proved she had poor foreign policy judgment.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Obama had the better of that argument. If Clinton had not made that vote, it is a virtual certainty that she would have been elected president in his stead.

But people who voted for Obama thinking he would sharply rein in George W. Bush's belligerent military adventurism were mostly disappointed. Obama did cut back in some ways, and at least did not start any major new wars. But he also appointed his hawkish primary opponent to the top foreign policy position, and mostly embraced the Bush security apparatus — or even expanded it, as with the use of drone assassination and dragnet surveillance. Furthermore, he did launch a major escalation in Afghanistan, and launch or enable multiple large-scale interventions in Libya, Syria, Somalia, and Yemen (not to mention deploying commando units in dozens of countries across the planet).

Every one of these interventions was a disastrous failure, by their own criteria for success. Afghanistan is no better than it was in 2009, while the other four are more or less smoking ruins. Yemen in particular — the Saudi intervention of which was and is enabled by extensive American support — is in the grips of a titanic humanitarian emergency, with hunger and the worst cholera epidemic in recorded history sweeping the land.

It was only towards the end of his presidency that Obama focused seriously on diplomacy instead of force — particularly through the appointment of John Kerry as secretary of state. Kerry pursued diplomatic engagement with tremendous energy, and achieved many notable successes, most importantly the nuclear deal with Iran. (Though he did also support the Saudi intervention in Yemen, to be fair.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

So it was somewhat surprising that not only did 2016-vintage Clinton not cleave to Obama's 2008 vision on foreign policy, as she mostly had during that campaign, she became somewhat more hawkish, promising aggressive confrontation with Russia and a continuation of all Obama's various interventions.

Worse still, under President Trump, Democrats have been shockingly cavalier about the Iran deal — by far Obama's best and most important foreign policy achievement. With the single exception of Bernie Sanders (an independent, but he caucuses with the party), Senate Democrats voted in lockstep for a new sanctions package that infuriated Iran — and helped pave the way for Trump to eventually abrogate the deal, as seems likely.

So it has fallen to Sanders to pick up the torch not just for the anti-war left, but for the more moderate liberal internationalism espoused by Obama in 2008. As Sanders argued at Westminster, foreign policy is not just about which unlucky Middle Eastern country will be bombed next — it's also about diplomacy, global inequality, climate change, and how America presents itself to the world through the treatment of its own citizenry. So not only did he argue that Iraq was a disaster and the Yemen intervention should be immediately halted, he argued that America should preserve the Iran deal, pursue international climate agreements, and stop operating the country on behalf of a tiny elite of financiers and corporate executives.

Making this argument is a steep uphill battle. One underrated aspect of extreme inequality is how it gives the stinking rich nearly bottomless resources to fund pressure groups to influence policy outside of narrowly self-interested topics like tax cuts. Belligerent wealthy warmongers have put massive resources behind think tanks, political pressure groups, and lobbyists — backed up by the power of military contractors, always happy for larger defense appropriations (and who are as often as not monopolists flagrantly ripping off the government). "The amount of resources being brought to bear behind a more hawkish vision is huge," a senior Sanders adviser told The Week.

However, there is a key fact about American imperialism in the 21st century that is often overlooked: It has disastrously harmed the national interest, by whatever metric you care to define it. In the old days of British imperialism, there was at least usually a self-interested motivation that made sense — subjugate India to provide a captive market for British textiles, make war on the Boers to capture the Witwatersrand gold, and so forth. The human costs of such imperialism were typically gruesome in the extreme, but they did provide a concrete, material benefit to the imperial metropole.

Similarly, American global leadership in the generation after the Second World War provided an inarguable strategic benefit in many respects — and not in such narrow beggar-thy-neighbor terms. Now, as Sanders rightly noted, this period saw many terrible interventions that later blew up in America's face, as with the CIA-backed coup in Iran in 1953, and also saw many alliances of convenience with brutal dictators. But American power also backstopped a diplomatic order in Western Europe and Japan that did create peace, stability, and prosperity, through the Marshall Plan, NATO, and other tools. The French-German border — once the site of clockwork blood-soaked conflict — has not seen a war in 72 years. That's not entirely America's doing, of course, but it is a large part of the story.

But America's various interventions and wars since the turn of the century have provided no such benefit. Various war profiteers have made out like bandits, to be sure, but the country as a whole has merely bled trillions in resources and thousands of lives into a bottomless abyss only to exacerbate the political chaos and violence in which terrorism thrives.

That's what makes Sanders' emphasis on aspects of foreign policy outside of the use of force so refreshing. America has not decisively won a war since 1945. Its greatest foreign policy successes since then have come through diplomacy, commerce, carefully built-up international institutions, and critically, moral behavior. As he said:

Foreign policy is about whether we continue to champion the values of freedom, democracy, and justice, values which have been a beacon of hope for people throughout the world, or whether we support undemocratic, repressive regimes, which torture, jail, and deny basic rights to their citizens. [Bernie Sanders]

Leftists have often been wary of such rhetoric, as neoconservatives have routinely leveraged it in support of their latest war of aggression. But is is possible to recognize the inability of America to impose these ideas at gunpoint — indeed, it would be hard to imagine a recent past providing better confirmation of this — while maintaining their general value. What's more, modern conflict is so expensive, and modern economies so complicated and fragile, that old-fashioned imperial pillaging is simply impossible.

For anyone with even a scrap of vision and long-term political sense, all that ought to provide a counterweight to the moneyed interests demanding more endless war. A more humble, realistic foreign policy, focused on diplomacy, conflict de-escalation, humanitarian aid, and upholding international law and treaties, really could redound to both the American benefit and that of humanity writ large. Democrats need to stop caving in to the war lobby and start thinking seriously — and morally — about the national interest.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

‘Space is one of the few areas of bipartisan agreement in Washington’

‘Space is one of the few areas of bipartisan agreement in Washington’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How robust is the rule of law in the US?

How robust is the rule of law in the US?In the Spotlight John Roberts says the Constitution is ‘unshaken,’ but tensions loom at the Supreme Court

-

Magazine solutions - December 26-January 2

Magazine solutions - December 26-January 2Puzzles and Quizzes Issue - December 26-January 2

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook