The creep of The Nutcracker

What the hell is going on with Godfather Drosselmeyer and what is he teaching our children?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Now that the holidays are upon us and the productions of The Nutcracker ballet are coming hard and fast, it's time to ask that age old question: What the hell is going on with Godfather Drosselmeyer?

The Nutcracker has always been a story about a young girl's journey into adulthood and sexual maturity, and as Drosselmeyer creeps around the stage this year, in the wake of Harvey Weinstein and Roy Moore, he reminds us that the journey has always been fraught.

If you haven't seen The Nutcracker in a while or have only absorbed bits of it through commercials playing Tchaikovsky's "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy" on infinite loop, the story goes like this: It's Christmas Eve at the Stahlbaum home, and daughter Clara makes herself useful preparing for a party, while her younger brother Fritz, who nowadays would clearly have been diagnosed with ADHD, makes trouble. Soon the guests arrive. While the adults are adulting, the children make their own fun, until a mysterious man appears, cloaked in black and wearing an eyepatch. This is Godfather Drosselmeyer, a clock and toymaker who, depending on the production, either entertains the children or genuinely frightens them.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Either way, he soon takes over the night's festivities. He produces uncanny, life-sized clockwork toys, which seem to come alive and dance for the guests. He hands out presents — dolls for the girls, swords for the boys. Clara, his special favorite, receives a wooden nutcracker, which everyone admires and which her jealous little brother quickly breaks. But Drosselmeyer bandages the toy and places it in a bed beneath the Christmas tree, where Clara will later fall asleep with it in her arms.

Things then get strange. At the stroke of midnight, Clara wakes to see Drosselmeyer on the grandfather clock, exercising what now appear to be magical powers. The room around her grows, or perhaps she shrinks. In the ballet's source story, E.T.F. Hoffman's The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, this moment is undeniably traumatic, and her account of it is the first of many that the adults around her will refuse to believe. The toys come to life and do battle with an evil mouse king and his troops. This is, after all, unbelievable, unless we remember that Drosselmeyer has already done something like it once before with his dancing automatons. In Hoffman's story, Drosselmeyer tells the girl, "it will all be over soon." But rather than being relieved she calls him "evil" (böser) and is paralyzed with fright.

Most versions of the ballet then jump to what happens in Hoffman's tale on a subsequent night, when the nutcracker, who has been under a spell of the mouse queen, takes his natural shape as a handsome prince and escorts Clara to the Land of Sweets. Leaving aside the blatant colonialism of the caricatures that follow, isn't it just a little creepy that Clara's good-looking escort begins as a gift from Drosselmeyer? In fact this toy, in Hoffman’s story, bears a "strange resemblance to Drosselmeyer" himself.

But that's not even half of it.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In the original, but not the ballet, the girl's vision is accompanied by a sharp feeling of pain, which she will later realize was caused by falling into a glass cabinet and lacerating her arm. Discovered by her mother in a pool of blood, she relates Drosselmeyer's role in her accident only to have her mother and the attending surgeon dismiss the "silly stuff" as the product of her "lively imagination." Godfather Drosselmeyer, however, privately suggests that he believes her. As one 19th-century translation put it, "smiling queerly," he "took the little girl on his lap, and spoke more softly than ever" as he confirmed that her dream contained some element of truth. It's hard not to get a little Freudian about all this, but even if we don't read it as some sort of sexual allegory, the dynamic is clear and unsettling.

Up to this point in the original, Drosselmeyer has wooed the girl with a special gift, awed her with his abilities as a technician and a magician, and degraded her by dismissing her as a "foolish child" (unverständig Kind) who could not appreciate his skill. Now he is teaching her to disbelieve her own experience unless it can be verified by a powerful man like himself. As the story continues, he will berate her for speaking "silly, stupid nonsense" (dummer einfältiger Schnack) when she tries to tell others. After being humiliated several times, she stops trying.

"A hundred times," Hoffman writes, "she thought of telling what had happened, to her mother, or to Luise, or at least to Fritz; but she asked herself, 'Will any of them believe me?'" Finally she withdraws into herself, which only warrants further criticism: "[I]nstead of playing as she used to do, she would sit still and silent, her thoughts far away, till everybody faulted her for being a little dreamer."

It was a similar form of manipulation that caused the actress and director Asia Argento to describe her encounters with Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein as "a scary fairy tale" and "a nightmare" in the story that initially exposed decades of Weinstein's abuse. Weinstein so thoroughly warped her perspectives of herself and their encounters, said Argento, that he began to "sound like he was my friend and he really appreciated me." One of failed Republican Senate candidate Roy Moore's accusers claimed he pushed her out of the car, saying: "You are a child. I am the district attorney of Etowah County. If you tell anyone about this, no one will believe you." He was almost certainly right.

In these cases, as in so many others that have come to light in recent weeks, we find similar differentials of power, age, and authority, leading women to keep quiet about what happened to them or even to adopt their abuser's account. As another of Weinstein's victims noted, "I just put it in a part of my brain and closed the door." Drosselmeyer may not be a sexual predator, but he exactly follows the sexual predator's script.

This matters because souvenir nutcrackers and swords are not the only things our children take home at the end of the show. For Clara as for The Nutcracker's young audiences, the journey to the Land of Sweets and back offers a magical glimpse of adulthood even as it raises suspicions about that vision. How much of it is Clara's? How much does Drosselmeyer produce by manipulating his machines or shaping Clara's imagination of herself? Drosselmeyer should disturb us not because he is aberrant, but because he enacts in sugar-plum form the strategies that men have long used to manage and control female sexuality.

Rather than a reason to run for the exits, however, I'd suggest that this could be one of The Nutcracker's redeeming qualities. Art has a remarkable power to make the familiar strange and allow us to see it anew — an effect Bertolt Brecht called verfremdung, or "alienation." Hoffman's nutcracker tale is strange, yet familiar, in exactly this way, especially as Clara internalizes the disbelief she encounters when she tries to tell her story.

A Nutcracker production that forced us to reckon with Drosselmeyer's true power would also allow us to consider what it would mean for Clara, or many Claras, to take it back. While Drosselmeyer is a master of gears and springs, after all, his real hold over Clara comes from understanding that everyone, including herself, will trust his account of her experience more than her own.

That's a hard nut, but it is ready to be cracked.

Blaine Greteman is a professor of English and Writing at the University of Iowa. His work has appeared at TIME, The New Republic, and Slate, and his first book was The Poetics and Politics of Youth, published by Cambridge University Press.

-

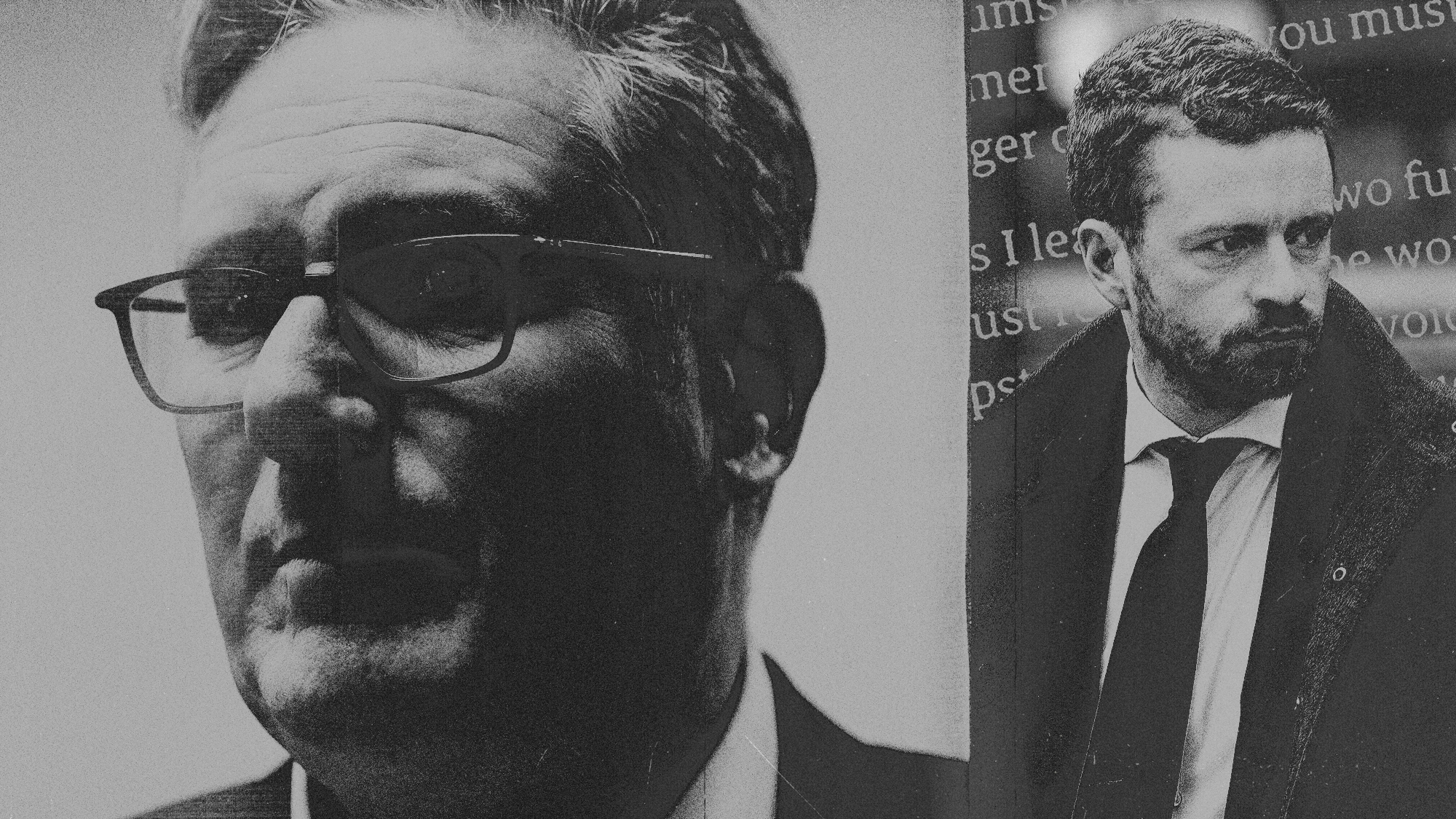

Who is Starmer without McSweeney?

Who is Starmer without McSweeney?Today’s Big Question Now he has lost his ‘punch bag’ for Labour’s recent failings, the prime minister is in ‘full-blown survival mode’

-

Hotel Sacher Wien: Vienna’s grandest hotel is fit for royalty

Hotel Sacher Wien: Vienna’s grandest hotel is fit for royaltyThe Week Recommends The five-star birthplace of the famous Sachertorte chocolate cake is celebrating its 150th anniversary

-

Where to begin with Portuguese wines

Where to begin with Portuguese winesThe Week Recommends Indulge in some delicious blends to celebrate the end of Dry January

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.