Women staged a shocking revolt at the Golden Globes

The sea of black turned out to be a more interesting experiment than anyone suspected

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For all their glitz, awards shows are famously dull affairs. The lovely rich don impossibly expensive costumes to thank people we don't know and it is our privilege to watch them, squeezing joy out of the connective tissue that makes the evening move. The host jokes. The music plays people off. And a meaningless ranking (Best This, Best That) forms and hardens into something like industry truth. There might be a couple of good speeches, but the main thrill an awards show offers is that it's live. There's margin for error. There's a slight risk that this tightly controlled spectacle featuring celebrities who we only see in the most curated contexts might go rogue. Basically, we watch for the surprises, for what isn't supposed to happen.

The Golden Globes has always shared the same basic structure as the stuffier Academy Awards, despite its reputation for being "the fun one." But last night's show, wrenched by the #MeToo movement, became something else entirely: It became a staged revolt against the way women were treated within the industry and outside it. Some of that disruption was planned. Some of it (like Natalie Portman's insertion of a single, powerful phrase) seemed spontaneous. The result wasn't just riveting; it was shocking. Recy Taylor, the woman kidnapped and gang-raped by six white men who were never prosecuted, was trending by the end of the night. Because of an awards show.

Basically, the Golden Globes developed into a contest between the framing device — the self-congratulatory awards show, the conventions of which virtually all the men in attendance blandly indulged — and the urgent subtext, which almost all the women's speeches rousingly addressed. Host Seth Meyers foresaw that and tried to split the difference. His monologue had some good moments ("good evening ladies and remaining gentlemen"), but he jittered with discomfort until a bit he did with Amy Poehler set a more relaxed tone. He ended by musing, with more respect than humor, on the Time's Up movement that led most of the women in the room to dress in black.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The challenge of striking a balance between these new and difficult conversations about assault and "who dressed you?" frivolity was evident on the red carpet. On Sunday morning, Amber Tamblyn published an op-ed in The New York Times explaining why "hundreds of women from the Time's Up movement will reject colorful gowns for black ones on the Golden Globes' red carpet and at related events across the country. Wearing black is not all we will be doing," she writes.

We will be doing away with the old spoken codes in favor of communicating boldly and directly: What we are wearing is not a statement of fashion. It is a statement of action. It is a direct message of resistance. Black because we are powerful when we stand together with all women across industry lines. Black because we're starting over, resetting the standard. Black because we're done being silenced and we're done with the silencers. Tonight is not a mourning. Tonight is an awakening. [The New York Times]

Despite plenty of skepticism over what many considered a stunt, the sea of black turned out to be a more interesting experiment than anyone suspected. For one thing, the fact that everyone (men and women alike) wore the same color highlighted some differences in how actors of different genders are questioned on the red carpet. Women always tend to be asked "who" they're wearing; the focus of their red carpet conversations drift, in consequence, toward giving credit to some other party for their artistry, with perhaps a cursory question or two about how excited they are to be nominated. Men tend to be asked more substantive questions about characters they've played and things they've done.

It was fascinating to watch that distinction morph in this reconfigured context. To be clear, men and women were still questioned differently. It's clear that many entertainment journalists deemed the issue too controversial to broach, effectively making it the job of women to discuss an issue for which men are mostly responsible. Irritating as that was, one unexpected effect — mainly because men on the red carpet were simply not asked about the Time's Up movement (even if they were wearing pins in support) — was a reversal: In a twist, the men seemed rather frivolous compared to their female colleagues.

The flip side is that the women in black were asked less about who made their clothes and more about the messaging behind those clothes. And even when they weren't, many turned the conversation that way anyway. My favorite such pivot was Michelle Williams' (who brought activist Tarana Burke, the founder of the #MeToo movement some years ago, as her guest). Asked how excited she was about her nomination for a Golden Globe for her role in All the Money in the World, Williams replied that she simply didn't remember: "That hasn't been on my mind for the last couple of weeks, we've been so excited about changing the carpet," she replied, going on to talk about the movement and her hopes for her daughter. Viola Davis emphasized the importance of listening to women without platforms. "There's no prerequisites to worthiness: You're born being worthy, and that's a message a lot of women need to hear," she said. Kerry Washington pivoted from talking about Scandal's last season to the Legal Defense fund for victims of sexual assault who don't have access to legal representation. "The reason we didn't just stay home," she said, was that "we shouldn't have to sit out the night, give up our seat at the table, our voice in this industry, because of bad behavior that wasn't ours."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And the women didn't shy away from awkward subjects. One aspect of Time's Up is how women are undervalued and underpaid. E!'s Catt Sadler left the network when she discovered a "massive" pay gap between herself and her male co-host that E! refused to make right. When E! pulled Debra Messing over for an interview, she took them to task:

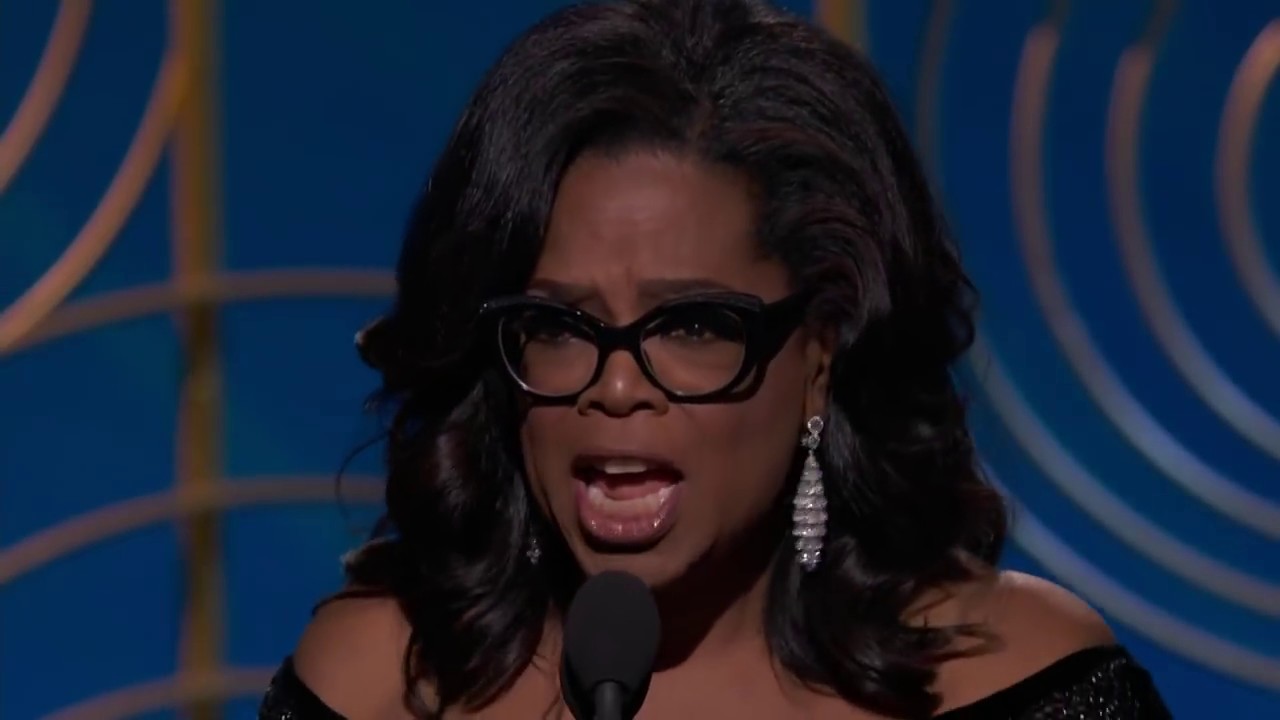

That trend continued during the actual awards, where the women spoke in ideals and gave speech after rousing speech about equality and a better world while the men at the microphone stuck to personal matters, congratulating themselves and their intimate circle and saying nothing at all about the Time's Up movement. The effect got more and more lopsided as the evening went on until Oprah Winfrey gave an oration while accepting her Cecil B. DeMille Award that was so stunning, I hesitate to excerpt it. It really demands watching in full:

An impossible act to follow; that speech catapulted the night into history, and got Recy Taylor (who never saw justice) trending on Twitter. The only way to follow that was by perhaps doing exactly what Natalie Portman did, to everyone's astonishment. She took the one scripted line she was given to say as she was presenting the nominees for best director and gave it a lethal twist: "And here are the all-male nominees," she said, quickly and without emphasis. It was an electric, disruptive moment. As The New Yorker's Emily Nussbaum put it:

Because here's the thing: Lady Bird, a film directed by a woman, won the Golden Globe for Best Picture for a musical or comedy and for Best Actress for a musical or comedy. That neither Lady Bird's director, Greta Gerwig, nor Get Out's Jordan Peele, got so much as a nomination was worth mentioning, and mention it Portman did. She made the omissions visible.

When Barbra Streisand took the stage, she took the point a bit further, saying she is the only woman to have ever won Best Director:

You know, that was 1984. That was 34 years ago. Folks! Time's up! We need more women directors, and more women to be nominated for Best Director. There are so many films out there that are so good directed by women. Anyway, I'm very proud to stand in a room with people who speak out against gender inequality, sexual harassment, and the pettiness that has poisoned our politics. And I'm proud that our industry, faced with uncomfortable truths, has vowed to change the way we do business. [Barbra Streisand]

As for the men, several made a point of thanking their female colleagues. But this was genuinely odd amid that sea of black dresses:

What's more, several of the male honorees have said, and been accused of doing, really awful things, including Gary Oldman, who received one of the biggest awards of the night for his performance as Winston Churchill in Darkest Hour.

The ceremony, in other words, was slightly out of sync with the conversations happening within it. Its winners and losers don't really reflect the new reality, even if its female presenters did. Get Out deserved much more than it got (nothing, despite its astounding critical and commercial success); Three Billboards probably deserved less. Gerwig should have been nominated for Best Director. But the point is less who should have won than what the tensions of the night showed about where we are in history. While Nicole Kidman talked about how her character in Big Little Lies reflects something true and difficult about abuse, the men who won for playing memorable abusers said nothing about their characters or the stories in which they appear. A stranger to the culture might have observed that while the women pushed the ceremony's constraints to start a conversation about how storytelling can further equality, the men remained stuck in an older awards show paradigm that focuses on the story of the self (and demands more time to tell it).

Frances McDormand nailed that difference with her customary gravitas: "As many of you know, I keep my politics private, but it was really great to be in this room tonight, and to be part of a tectonic shift in our industry's power structure. Trust me: The women in this room tonight are not here for the food. We are here for the work. Thank you."

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.