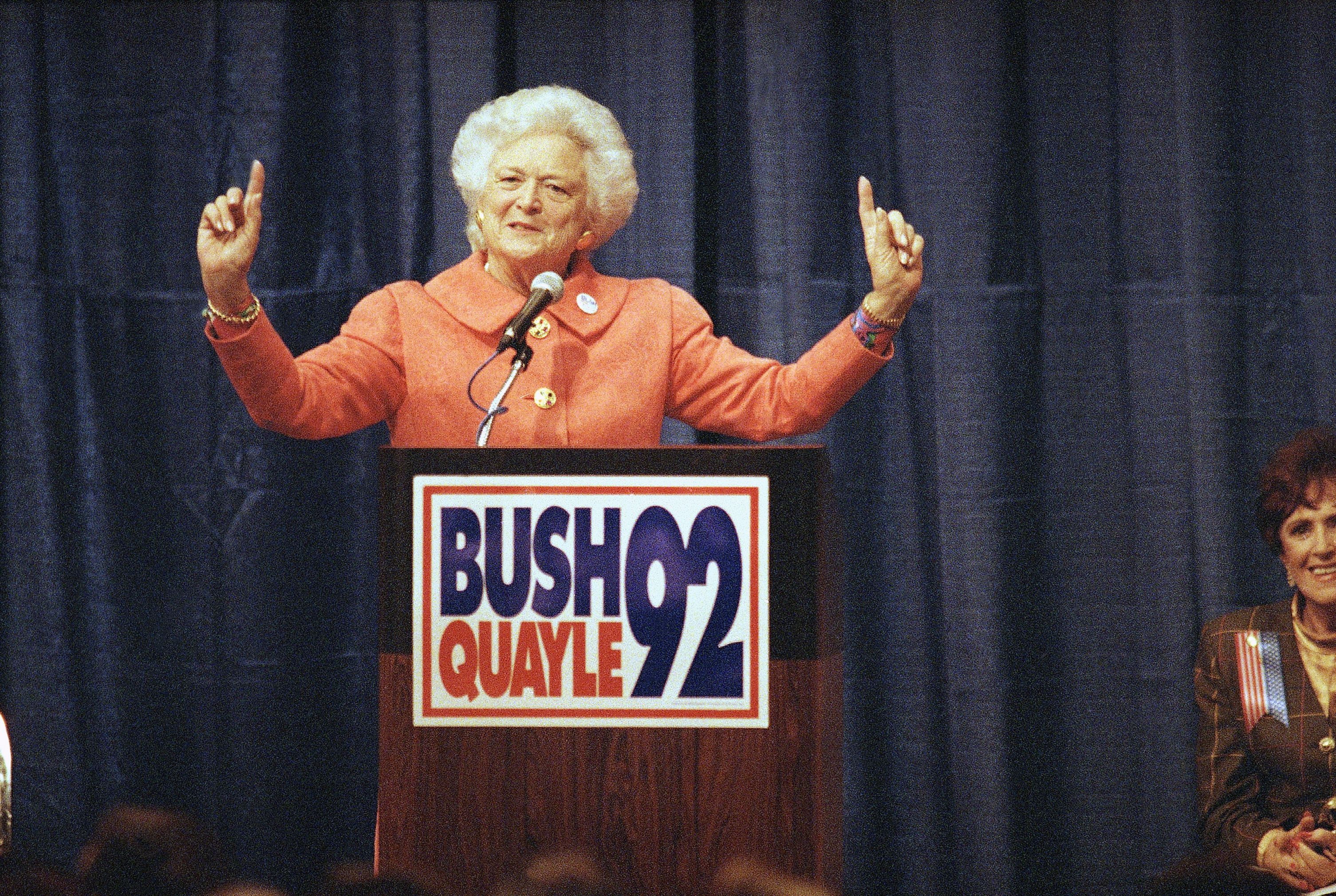

Barbara Bush was one of the very best Americans

The Bush family’s loss is the country’s

Barbara Bush, who died on Tuesday at the grand age of 92, was perhaps the only living former resident of the White House with whom I should have been glad to spend an afternoon.

For at least three decades she was the most amusing, witty, outspoken, and, in her way, unabashedly reactionary figure in American public life. She was also extraordinarily beautiful even, indeed perhaps especially so, in her old age. She possessed all the virtues of her vanished class, the old WASP establishment whose sons once held most of the seats in the House of Representatives and ran our overseas embassies and our intelligence services and whose unwillingness to lead — or was it a loss of nerve? — in the post-war era changed American politics forever, for good or ill.

I suppose some obituary writers will hope to claim her for conservatism. If she was a conservative she was one of a very eccentric and independent sort. She loathed crime, racism, obscenity, the National Rifle Association ("offensive" and "paranoiac" was her verdict after the Oklahoma City bombing), the internet ("Anyone can start their own website and many have"), and every kind of fanaticism and cruelty. She loved her country, her family, her dogs, the sea, needlepoint, and having lunch with ambassadors' wives and members of the Episcopal clergy.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Like her husband, she was a pre-Goldwater Republican to whom classical liberalism, with its absurd dogmas and naked appeals to our basest impulses, was incomprehensible. For the older generation of Bushes, governing meant doing what was best for the country, not courting the lunatic speculations of think-tank vice presidents. Historians will remember the presidency of George H.W. Bush as among the most successful of the last century, a blessedly sober end to the madness of the Cold War. This did not mean that she had a high opinion of her children's political gifts; not even Donald Trump spoke more contemptuously of Jeb Bush's presidential candidacy than Barbara did in late 2015.

She did not always play to type. No one will be surprised to learn that she was very keen on Mary Higgins Clark and other popular crime novelists, but she was also an admirer of Kazuo Ishiguro and Elizabeth Jane Howard. And very few readers of her two charming volumes of memoirs will be prepared for her very frank and moving account of her struggles with depression:

It is still not easy to talk about today, and I certainly didn't talk about it then. I felt ashamed. I had a husband whom I adored, the world's greatest children, more friends than I could see — and I was severely depressed. I hid it from everyone, including my closest friends. … Sometimes the pain was so great I felt the urge to drive into a tree or an oncoming car. When that happened, I would pull over to the side of the road until I felt okay. [Barbara Bush: A Memoir]

It is almost impossible now to imagine how difficult it must have been for a woman of her age and class to write those sentences. Her "code," as she refers to it, was learned in childhood, and it taught her that the feelings of others always mattered more than one's own, and that there was no problem that could not be solved with a self-deprecating joke and perhaps another visit to the drink cart. As she aged she often found herself wishing that more of her fellow Americans shared her reticence and her dismissive attitude toward what has become of our popular culture. She often spoke wistfully of a time when "drugs, sex, and violence were not constantly thrust at us by television."

In recent years I have found it difficult to look at Mrs. Bush without thinking of my own late great-grandmother, who was born two years before her in 1923. Their backgrounds could not have been more different — her father was a very poor farmer in rural Michigan — but the many things Ruth Bond and Barbara Bush shared seem somehow more important. Both of them were sharp-tongued, commonsensical, self-effacing women (a "nice fat old lady" is how Mrs. Bush liked to think of herself) to whom duty and kindness, however idiosyncratically expressed at times, mattered above all else; both were fond of music and rather old-fashioned clothes and jewelry and of shocking younger people out of their mindless complacency. I recall once visiting her in the hospital when I was aged 12 or 13 and happened to have on a Who's Next? t-shirt. "Why aren't you wearing a shirt?" she asked me. "But I am wearing a shirt!" I insisted. "A shirt has a collar and buttons. You are wearing an undergarment." This is exactly the sort of thing one can imagine the late Mrs. Bush saying to one of her great-grandchildren.

I suspect that I am not the only American for whom the death of our greatest modern first lady calls forth the memories of deceased relations from a generation whose greatness we have really only begun to appreciate. The Bush family's loss is the country's. It is also a reminder that while Americans have gained much in the post-war era we have also lost a great many valuable things — manners, habits, loyalties, affections, a universal conception of politics as the maintenance of the common good — that now seem all but irrecoverable.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

Critics' choice: Three takes on tavern dining

Critics' choice: Three takes on tavern diningFeature A second Minetta Tavern, A 1946 dining experience, and a menu with a mission

By The Week US

-

Film reviews: Warfare and A Minecraft Movie

Film reviews: Warfare and A Minecraft MovieFeature A combat film that puts us in the thick of it and five misfits fall into a cubic-world adventure

By The Week US

-

What to know before lending money to family or friends

What to know before lending money to family or friendsthe explainer Ensure both your relationship and your finances remain intact

By Becca Stanek, The Week US

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

By The Week Staff

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK

-

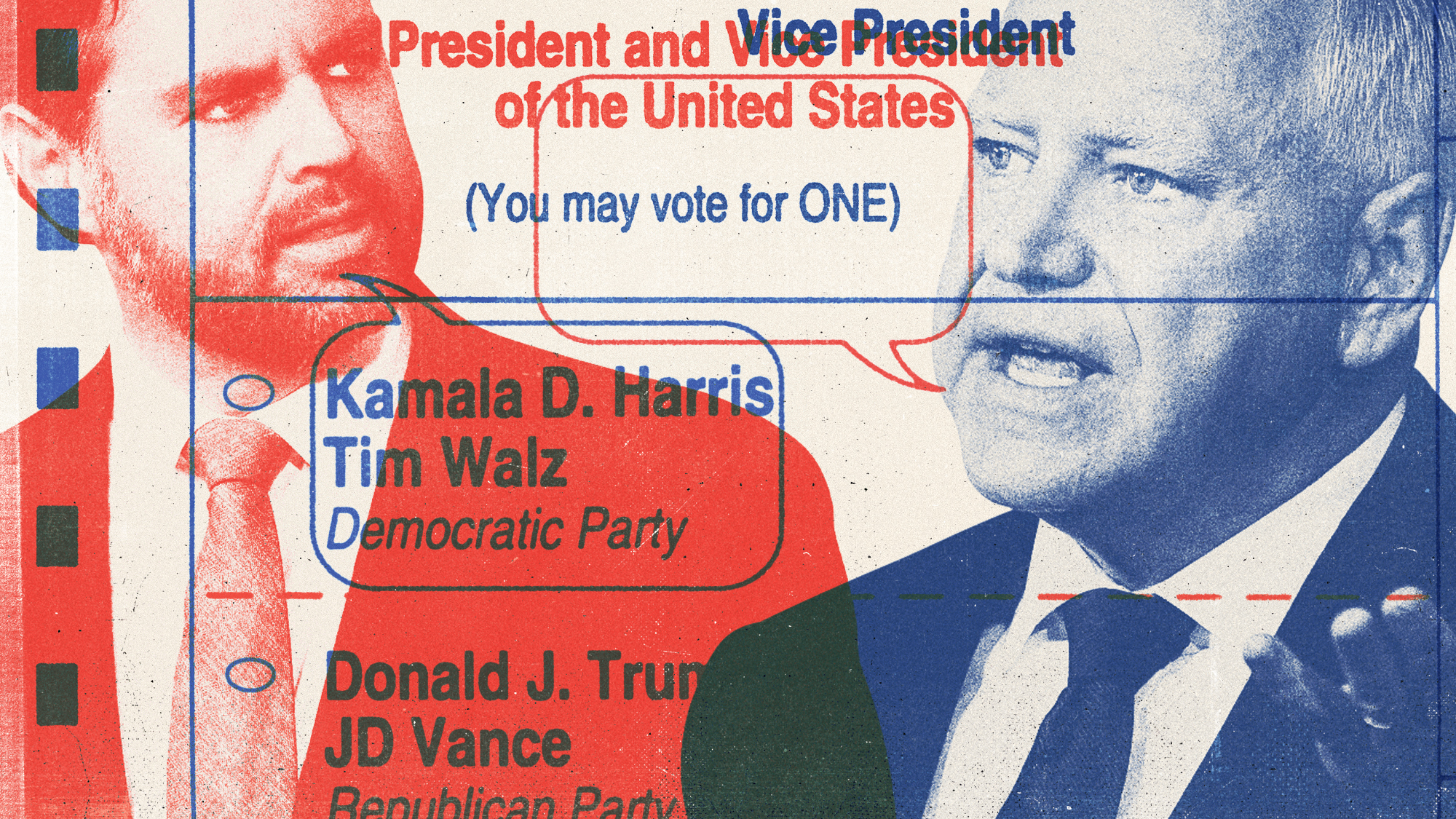

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?

By The Week UK

-

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?Today's Big Question 'Diametrically opposed' candidates showed 'a lot of commonality' on some issues, but offered competing visions for America's future and democracy

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK