Why everyone hates Solo

Solo isn't a movie so much as it is a marketing concept. Is anyone surprised there's a backlash?

The mounting consensus around Solo: A Star Wars Story seems to be that a Star Wars fan or completist should probably see it, but, ugh, it will be a chore. And even this limp resignation is far kinder than the blazing, let-loose-the-dogs-of-war kind of hatred that some Star Wars fans have shown.

When the film's first trailer debuted on Super Bowl Sunday, the headlines evinced an already-over-it malaise ("Here's Why Nobody Cares About Solo: A Star Wars Story"), the fancasts speculated that it would be "a colossal disaster," and the Reddit threads — well, the Reddit threads were exactly what one might expect, gleefully sharing rumors that Disney "knows this movie is a stinker and is expecting it to fail." The drama around Solo's production — the gladiatorial casting process that put every white actor under 30 inside the arena; the original directors' clashes with producer Kathleen Kennedy and replacement with Hollywood stalwart Ron Howard; and the exhaustive rewrites, reshoots, and re-interpretations — soon eclipsed any legitimate interest in, or appraisal of, the film.

Critics who have seen the film, however, suggest that it is not an intergalactic trainwreck; it's perfectly serviceable, a relatively smooth and efficient ride that doesn't veer off the tracks and rolls into each of its designated stations right on time — certainly nothing that deserves to be incinerated in a bonfire of snark and righteous indignation. So why are so many fans already convinced that they hate it?

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It's tempting to view this preemptive backlash as another example of a fandom that is already prone to hair-trigger tantrums — like everyone who didn't just dislike The Last Jedi, but cursed Rian Johnson for ruining their entire childhoods — kicking its feet and crying and holding its breath over some perceived slight. However, on a more elemental level, this backlash isn't a matter of kiddie petulance — it's not anger at Solo as a movie, but at Solo as a marketing concept, a cynical cash grab that traps a character who remains so beloved precisely because of his roguish, iconoclastic persona in the carbonite of a rote, uninspired origin story. Solo's perfect serviceability is, ironically, the most incendiary thing about it.

Lindsey Romain, a culture writer who has written comprehensively, and exquisitely, about the Star Wars movies, tells me that the trouble with Solo is "the iconic nature of [Harrison] Ford in the role, the desire to see the non-episode films step outside of timelines we've already seen, and 'prequel syndrome' of having things reference in the original timeline explained to us." Indeed, Ford's portrayal of the smirking smuggler launched many an adolescent (and, um, post-adolescent) fantasy, a plethora of toys and Halloween costumes, and infinite hours of online debate (for the record: Han totally shot first) — because there is something indelibly intimate about watching a performer create a character who feels both wholly alive in the moment-to-moment, and also totally lived-in.

Ford ripened the old tropes of the Humphrey Bogart-esque cynic with a hidden heart of brass that, with some polishing, becomes a heart of gold, and the quick-drawing cowboy who is equally reckless and canny, while still making the character uniquely his own. There's something galling about shoehorning a young actor who survived a Hollywood Hunger Games to do a paint-by-numbers version of a franchise-defining performance. In the bluntly titled essay "Why I Want Solo: A Star Wars Story to Fail," Dani Di Placido argues that "Han Solo isn't about the character, or the vest, or the attitude … It was the formidable charisma of Harrison Ford that turned him into a pop culture juggernaut." Di Placido sites Ford's famously ad-libbed "I know" to Princess Leia's "I love you" as evidence that he knew the character more intimately than even George Lucas did. "Going backward to tack on some new, Ford-less story about how the character 'became' Han Solo, feels almost like some kind of narrative vandalism," he writes.

Ford's original portrayal, and the entire original trilogy, weren't specifically designed to become the pop cultural institutions they are today — they are deeply felt, emotionally intuitive works that resonate because of their uniqueness, their combination of individual quirk and collective attachment to powerful, century-spanning archetypes — that happened by happy accident. Yet films like Solo, or the much-reviled prequels, are created solely to be bricks in the walls of those institutions. It's understandable, even condonable, that people who called dibs on Han Solo during yet another playground 'round' of Star Wars, hours spent chasing each other with plastic blasters and paper Stormtrooper masks, would deeply resent reducing that character to his vest and his attitude, and treating that vest and that attitude as so much spackle.

In an interview, Logan Lerman, one of the actors who read for Solo, decried the "studio films that are just so formulaic and business-driven … just a bunch of executives sitting in their offices going 'what properties' … do we have that we can reformat and tackle this year. It's all so repetitive." Thinking about the concept of a film, and a character, as an intellectual property, can reduce the emotional intensity, the exquisite messiness, of being a fan, into something so cold and transactional: We are not appreciators of work, but open wallets waiting to be pillaged. And Solo is nakedly, unabashedly, a property (as if the film's current subtitle wasn't on the nose enough, the original working title of Young Han Solo bluntly articulates the lack of originality). Many fans want to see more stories in a galaxy far, far away, stories that don't use familiar characters, timelines, or events as a passionless shorthand; instead of quick, narrative graffiti, they want filmmakers to paint a broader, and more detailed, portrait.

It's telling that Star Wars: The Clone Wars, an animated film and subsequent series set during the eponymous battles, was one of the most critically respected and fan-beloved Star Wars stories in recent memory. Though the Clone Wars series featured a pre-Vader Anakin Skywalker, it introduced a range of new characters, including Ahsoka Tano, a teenage girl Jedi (who would go on to feature prominently in a follow-up series, Star Wars: Rebels), and it gave those characters depth and mettle. It's equally telling that Donald Glover's delightfully fey portrayal of Lando Calrissian and the introduction of Lando's co-pilot, the freedom-fighter droid L3-37 are the only things to intrigue, even excite, Solo skeptics — precisely because they are the most organic, individual elements of the film. Even though The Last Jedi proved to be, shall we say (and to say the least), controversial, its revisionist take on the franchise has inspired no shortage of passionate defenders.

Yes, Star Wars is an incredibly lucrative property, and yes, fandom all around the world made it that way by snatching up a myriad of prequel and sequel comics and novels and lining up to see the films — but the transparent property-ness of Solo seems like something of a breaking point. Even later-day additions to the canon, like Rogue One or The Force Awakens or The Last Jedi, do valuable work in reinterpreting the Star Wars mythos for the women and people of color who were forced to sit out on those old schoolyard reenactments of Return of the Jedi. What, exactly, is the purpose of a young Han Solo movie? Going back to a twentysomething Han Solo's story now that we know the full arc of his life — including his tragic death at the end of his own son's lightsaber — feels not only unnecessary, but downright maudlin (especially when that son's most famous line is "Let the past die. Kill it if you have to.").

There's no denying that swathes of the Star Wars fandom are, frankly, toxic, and that a lot of the fan-based gatekeeping is designed to Make the Galaxy Great Again, or preserve a white, hetero-masculine vision of the franchise. Still, the backlash to Solo (or, at least, the backlash that doesn't degenerate into death threats and trolling) is more reflective and nuanced. It demands that the studio stop treating this deep and varied universe as a mere property and start developing stories that don't reflect the same old, same old (emphasis on the old).

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Laura Bogart is a featured writer for Salon and a regular contributor to DAME magazine. Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, CityLab, The Guardian, SPIN, Complex, IndieWire, GOOD, and Refinery29, among other publications. Her first novel, Don't You Know That I Love You?, is forthcoming from Dzanc.

-

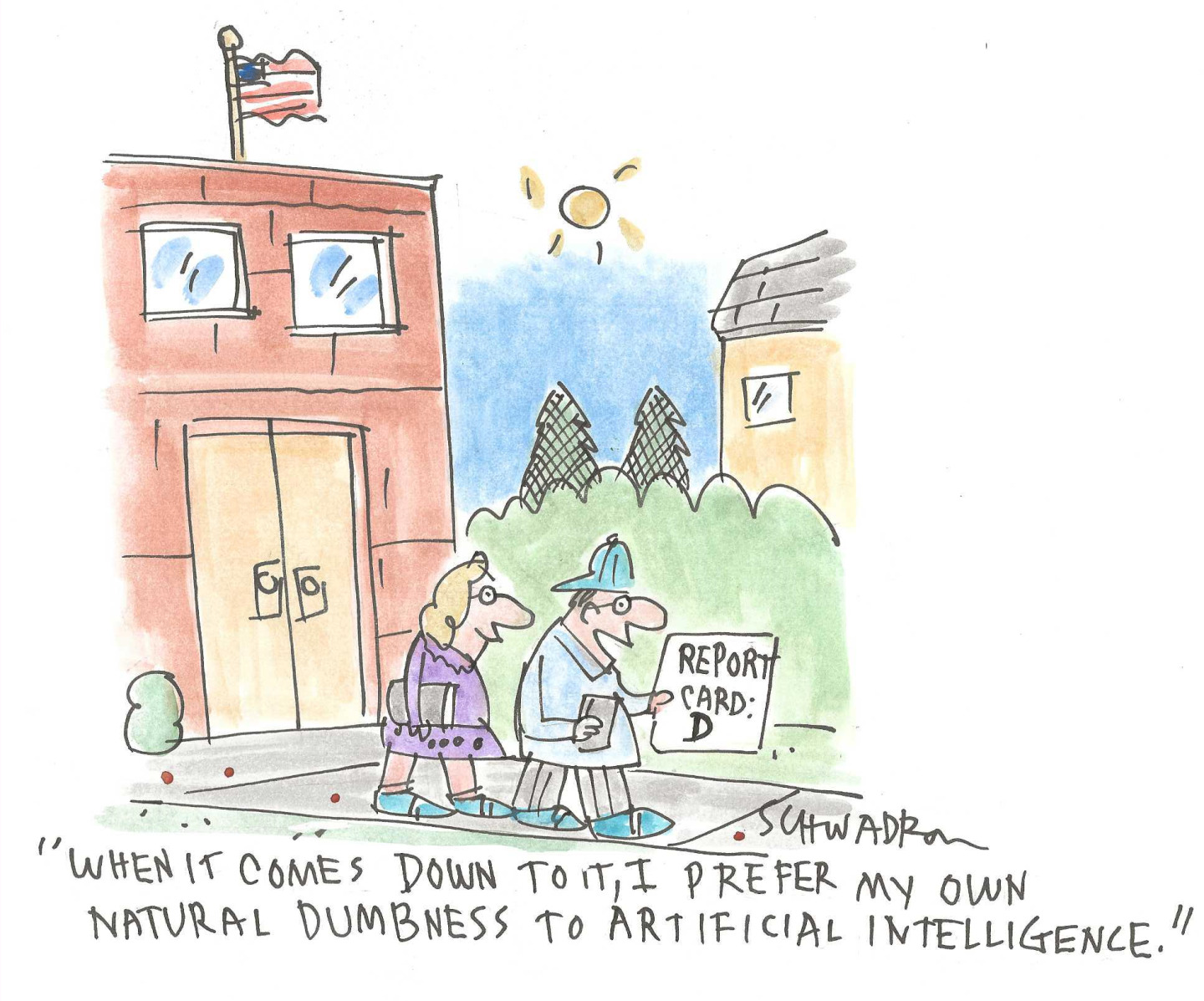

Today's political cartoons - May 10, 2025

Today's political cartoons - May 10, 2025Cartoons Saturday's cartoons - artificial intelligence, cryptocurrency, and more

-

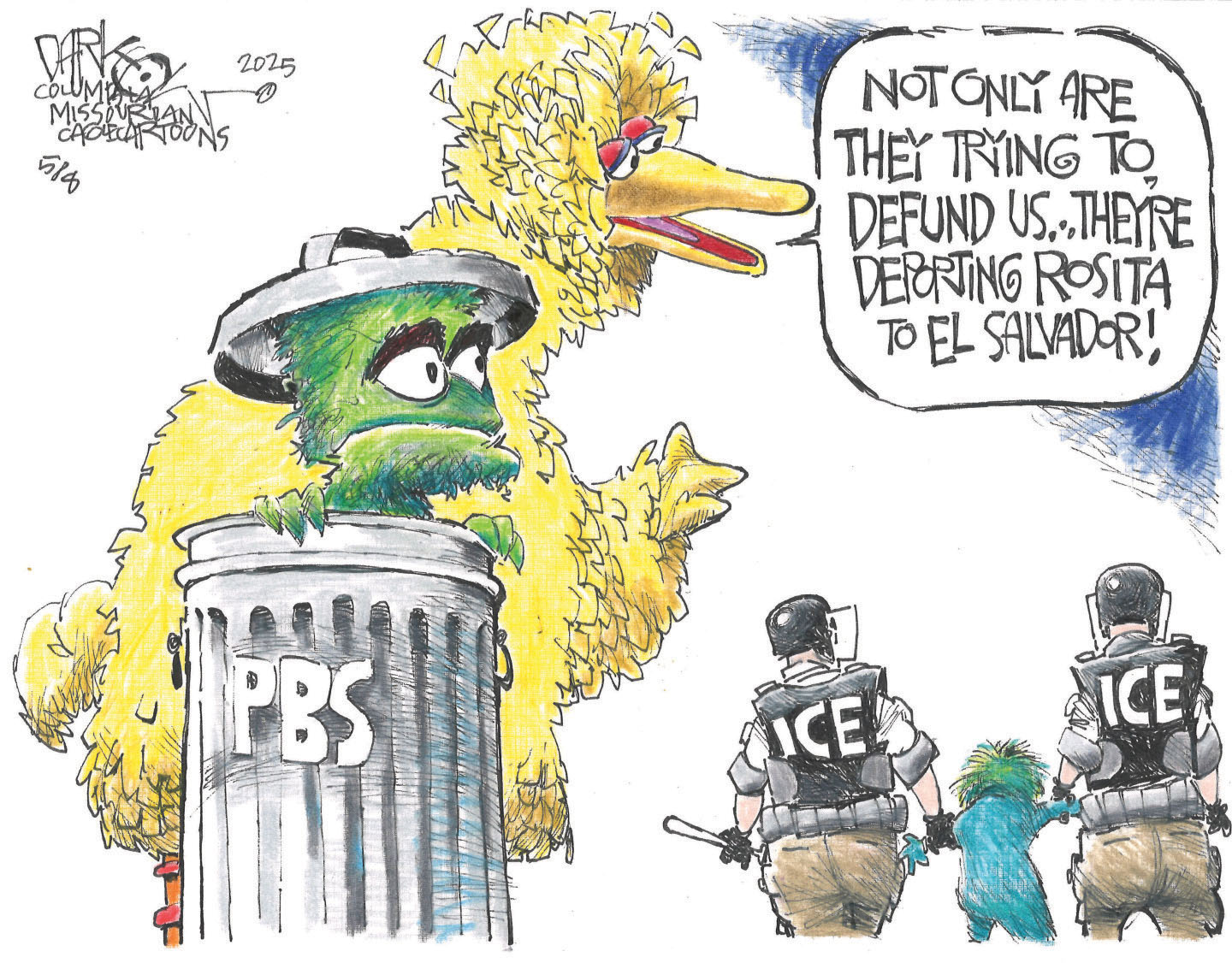

5 streetwise cartoons about defunding PBS

5 streetwise cartoons about defunding PBSCartoons Artists take on immigrant puppets, defense spending, and more

-

Dark chocolate macadamia cookies recipe

Dark chocolate macadamia cookies recipeThe Week Recommends These one-bowl cookies will melt in your mouth

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.