Why America's judges should stay out of gerrymandering

Leave this one to the politicians

The Supreme Court is ducking the gerrymandering question — as well they should. Redistricting is and always should have been a political process, and not something the judicial branch should weigh in on, except in a few exceptional circumstances.

Many liberals have long been furious by the GOP's successful gerrymandering of congressional districts for political gain in the wake of the 2010 census. As my colleague Scott Lemieux writes:

[W]hile partisan gerrymandering goes back to the earliest day of the republic, computer technology has made the problem much more dire. Democrats could win the popular vote in the upcoming midterms by 6 or 7 points and still not gain control of the House ... [The Week]

It's not hard to see why liberal activists are furious at this situation. But that hardly means there is a legitimate judicial rationale to end politicians' redistricting processes.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Indeed, despite efforts by activists to use the judiciary to overcome partisan outcomes in redistricting, and despite indications that the high court had some interest in it, multiple Supreme Court decisions announced in the last week indicate the effort is on life support, if not entirely dead. Good.

At first, it appeared that the Supreme Court had an agenda in mind. The court granted cert in multiple challenges to redistricting maps on the basis of partisan outcomes. The justices also declined an opportunity to reverse Pennsylvania's Supreme Court decision to preserve a redistricting map after that court ruled it in violation of the state constitution. Three other cases in North Carolina, Wisconsin, and Maryland all came under consideration for this term, and anti-gerrymandering activists held out considerable hope that the court would broaden its oversight on this critical once-per-decade process, in which lawmakers draw the boundaries of legislative districts, and always with an eye toward maximizing their own political advantages.

Instead, last week's decision in Gill v. Whitford was the first warning shot across the bow of activists. While the court sent the case back to Wisconsin in its first conclusive action on partisan gerrymandering, rather than dismiss it altogether, the opinion from a nominally unanimous court set the bar for judicial intervention high — and arguably unreachable. Chief Justice John Roberts declared that the plaintiffs had failed to demonstrate standing for the lawsuit, and that the remand would give them the opportunity to try again.

However, Roberts and the court have made that almost impossible for the purposes of attacking partisan outcomes in redistricting. Roberts noted that intervention in voting issues requires that plaintiffs to demonstrate "individual and personal injury" to the right to vote, not a collective right to a particular outcome. During the original trial, Roberts noted, the plaintiffs opposing the redistricting performed by the Republican-controlled legislature "instead rested their case on their theory of statewide injury to Wisconsin Democrats," on the basis that they failed to achieve a Democratic majority in the state legislature, despite having larger proportion of registered voters. "Under the Court's cases to date," Roberts pointed out, "that is a collective political interest, not an individual legal interest." The entire case, Roberts concluded, was "about group political interests, not individual legal rights."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Two other steps taken by the court underscored the court's aversion to putting the courts in the middle of the partisan process of redistricting. The court issued orders reversing a lower court ruling that threw out a Republican redistricting map in North Carolina, with instructions for the lower court to consider the standing requirements in Gill before making any further rulings. They also rejected a request by Republicans to enjoin the use of a redistricting map drawn up in Maryland by a Democrat-dominated legislature.

If the court sticks to the standing issue in the form presented in Gill, then gerrymandering lawsuits based on partisan representation is entirely dead. And it should be dead, because redistricting is a political process, not a legal process. Except in a narrow set of circumstances, it's a process for which voters should hold politicians accountable rather than have judges impose their own preferred solutions.

The narrow set of exceptions that require the court's interventions in redistricting cases rely on the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution and the Voting Rights Act, and are limited to protecting the "individual and personal" right to vote. Those circumstances involve immutable characteristics of the individual voter and any systemic efforts to impede the effective casting of votes on that basis. For that reason, the court has a long history of interventions in redistricting plans. Even there, though, Monday's ruling in Abbott v. Perez appeared to push courts to a narrower interpretation of its authority in relation to state legislatures and minority representation, with two of the concurring justices (Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch) arguing that the Voting Rights Act doesn't apply to redistricting at all.

Needless to say, the Voting Rights Act doesn't apply to Democrats or Republicans either in the sense of proportional representation in legislatures, and neither do the 14th and 15th Amendments. It may not seem like it these days, but party affiliation is a mutable characteristic, just as are other less formal affiliations such as progressives, conservatives, moderates, and so on. Those are voluntary associations that change over time, part of the very nature of the "individual and personal" right to vote. Redistricting does not affect the ability to cast those votes, especially not on the basis of being a Democrat or a Republican, categories which can and do change on an individual and group basis.

The ruling in Gill may not have conclusively settled the question for all time, which will regrettably require courts to continue dealing with demands for judicially imposed proportional representation. However, the unanimous decision to enforce standing and to reject demands on the basis of "group political interests" is a welcome step in removing inherently political issues from the courts. The best solution for parties that fail to win their preferred proportion of elections is to find ways to appeal to voters, not file appeals to spite them.

Edward Morrissey has been writing about politics since 2003 in his blog, Captain's Quarters, and now writes for HotAir.com. His columns have appeared in the Washington Post, the New York Post, The New York Sun, the Washington Times, and other newspapers. Morrissey has a daily Internet talk show on politics and culture at Hot Air. Since 2004, Morrissey has had a weekend talk radio show in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area and often fills in as a guest on Salem Radio Network's nationally-syndicated shows. He lives in the Twin Cities area of Minnesota with his wife, son and daughter-in-law, and his two granddaughters. Morrissey's new book, GOING RED, will be published by Crown Forum on April 5, 2016.

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

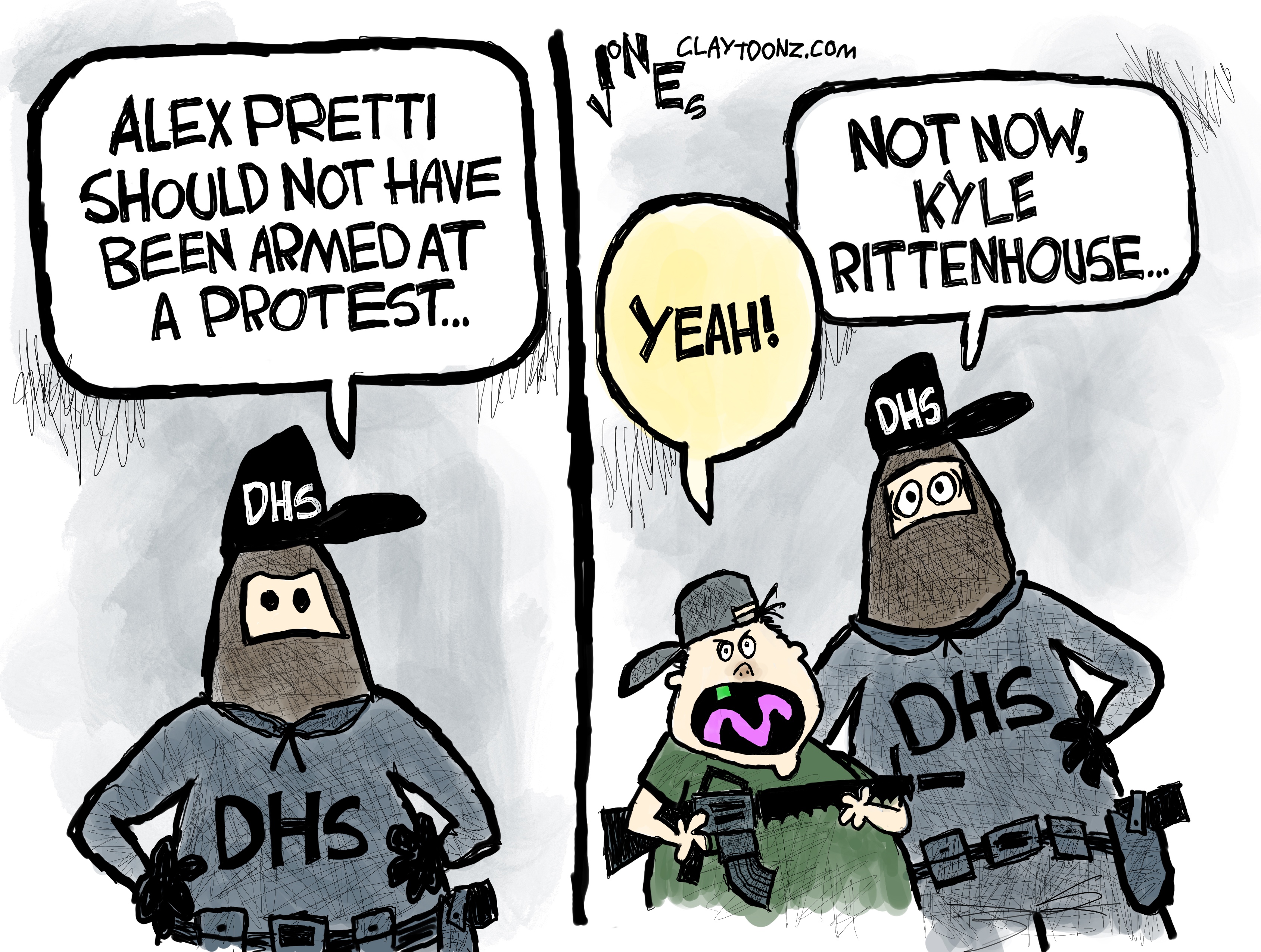

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second Amendment

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second AmendmentCartoons Artists take on Kyle Rittenhouse, the blame game, and more

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred