The passage of time cannot absolve Brett Kavanaugh — or anyone

A sin does not, with age, cease to be a sin. Time does not itself absolve.

Distance lessens the severity of our experience of evil.

We speak, unaffected, of the brutal death of dozens in a far off land. Comedy, as the saying goes, is "tragedy plus time." I've snickered at a 14th century description of Italian plague victims' corpses stacked "just as one makes lasagna with layers of pasta and cheese." A century after the sinking of the Titanic, children can scream in glee as they slip down an inflatable slide modeled on the moment panicked hundreds met an icy demise.

This is the way our brains work, and it is undoubtedly necessary if we are to cope with the knowledge of good and evil in our world. But we delude ourselves if we think that lessened experience of evil lessens the reality of the evil in question.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A sin does not, with age, cease to be a sin. Time does not itself absolve. Removal is not repentance.

It is easy to understand this when we ourselves have been wronged. Forgiving an old offense absent due apology and atonement is difficult precisely because the evil has not changed with time. But we are apt to forget this indelibility when it is convenient, when it serves us or our own.

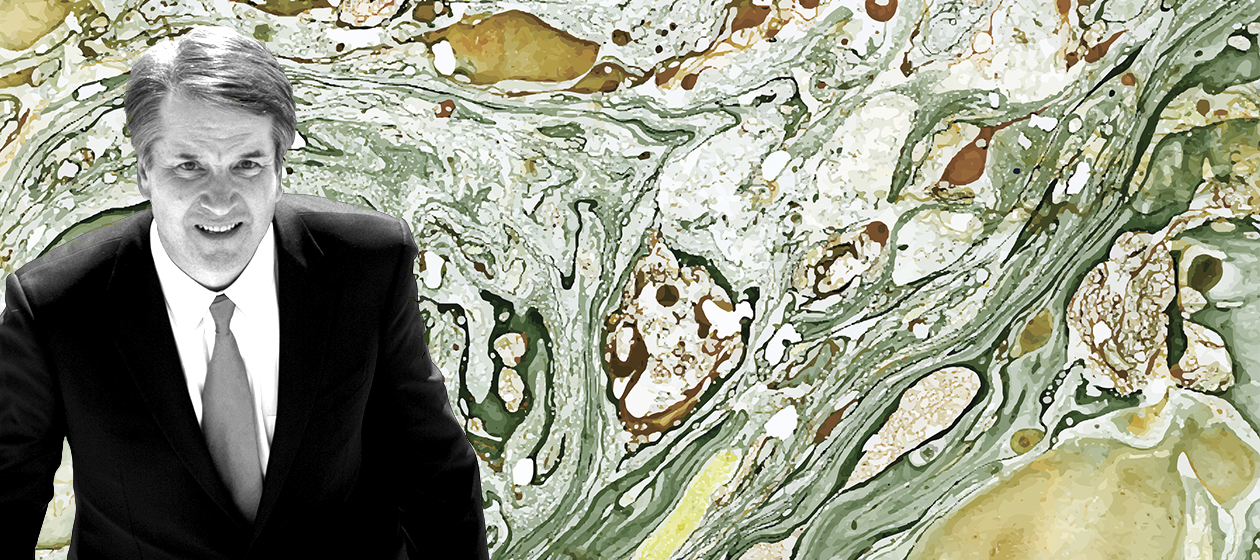

That selfish lethe is on display now in the sexual assault allegation scandal surrounding Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh. Though I find her story credible, I don't know definitively whether Kavanaugh tried to rape Christine Blasey Ford when they were both teenagers at a house party in the 1980s, and I have no intention of trying to settle that perhaps insoluble debate. (Kavanaugh categorically denies the allegations.)

My interest here is in Kavanaugh's defenders, particularly in the way many conservatives and Christians — I count myself among the latter, though no longer the former — have sought to preserve his path to our country's highest court. Some have simply argued that Ford's story is false or misremembered. Others have taken a fallback position in which two claims have dominated. Kavanaugh didn't do it, they say, but if he'd done it, this sexual assault would not be disqualifying because, one, it happened many years ago and, two, teenage boys are universally terrible creatures possessed of unformed brains and malformed morals.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"I do not understand why the loutish drunken behavior of a 17-year-old high school boy has anything to tell us about the character of a 53-year-old judge," tweeted The American Conservative's Rod Dreher in a representative comment. "By God's grace (literally), I am not the same person I was at 17. This is a terrible standard to establish in public life."

Dreher was far from the only one to take this tack. "If the story is true," opined The Daily Wire's Matt Walsh, "we now have to decide whether a man is unqualified for the Supreme Court because he drunkenly groped a girl 35 years ago when he was 17. I'm going to answer 'no' on that one." A Wall Street Journal op-ed described the alleged assault as something that happened "an awfully long time ago, back in Ronald Reagan's time, when the actors in the drama were minors and (the boys, anyway) under the blurring influence of alcohol and adolescent hormones."

Again, Kavanaugh himself categorically denies the allegations, which is much wiser than shrugging them off. But the mitigation approach Kavanaugh's defenders have crafted is not simply poor strategy. It is morally wrong.

While mulling this story after the news of Ford's identity broke over the weekend, I came across a quote from C.S. Lewis' slim volume of theodicy, The Problem of Pain. "We have a strange illusion that mere time cancels sin," Lewis wrote. "I have heard others, and I have heard myself, recounting cruelties and falsehoods committed in boyhood as if they were no concern of the present speaker's, and even with laughter."

"But mere time does nothing either to the fact or to the guilt of a sin," he continues. "The guilt is washed out not by time but by repentance and the blood of Christ: If we have repented these early sins we should remember the price of our forgiveness and be humble."

Furthermore, Lewis goes on, "we must guard against the feeling that there is 'safety in numbers,'" for it "is natural to feel that if all men are as bad as the Christians say, then badness must be very excusable." Really, argues Lewis, this repetition of evil is part of the indictment against it. "Everyone does it" (or "everyone does it at that age") is no defense, merely an exposure of how rotten the place in which everyone does it has become.

Indeed, that universality of evil, so far from justifying us, shows how deep our corruption runs. It points to what Christians — like Lewis, myself, and many of those now making this reprehensible defense of Kavanaugh — would call, by various turns of theological preference, humanity's sin nature, or total depravity, or the "bondage to decay" from which all creation awaits liberation to be "brought into the freedom and glory of the children of God." Yes, others have responsibility for evil. That does not negate mine.

Lewis rightly argues neither passage of time nor prevalence of guilt excuses our sin, and it is a lesson we would do well to heed as the debate over Ford's allegation continues.

None of this is to say old sins must always fester, or that childhood evil should ruin our whole lives. (Like other advocates of criminal justice reform, the question of consequences for juvenile crime is a conversation I would like to cultivate, but the Kavanaugh scandal is not the proper substrate.)

The way we deal with the reality of our old evils is repentance, something our culture — especially in the public square — does not do terribly well. Dreher himself glances at this subject in a blog post following his tweet: "I am only a couple of years younger than Kavanaugh, and I was part of a heavy teenage drinking culture," he writes. "I am certain that I never did anything like [what Ford alleges] — though maybe I did, and was too drunk to recall — but when I think about how much my crowd (boys and girls both) drank, and how stupid we got with sexual behavior under the influence, I am ashamed."

If Kavanaugh did it, is he ashamed? His defenders, those arguing that the allegation shouldn't matter because it was a long time ago and 17-year-old boys are by nature awful beasts, do not seem to care. Their dual volleys render repentance irrelevant. Time and age alone are held to exonerate.

They do not. And that, as The Atlantic's Caitlin Flanagan observes in a compelling piece, "is why the mistake of a 17-year-old kid still matters," and why a thorough investigation is so necessary.

If Kavanaugh is innocent, I share his supporters' hope that his name is cleared. If he is guilty, I share his opponents' hope that proof of truth will out. But what none of us should share is this feckless effort to offer absolution without confession, to allow time and the end of youth to do the work in us that repentance, apology, and restitution ought to do. Who is seated next on the Supreme Court is important, but whether we can recognize and renounce our own evil is more important still. In that we may find mercy.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

7 bars with comforting cocktails and great hospitality

7 bars with comforting cocktails and great hospitalitythe week recommends Winter is a fine time for going out and drinking up

-

7 recipes that meet you wherever you are during winter

7 recipes that meet you wherever you are during winterthe week recommends Low-key January and decadent holiday eating are all accounted for

-

Nine best TV shows of the year

Nine best TV shows of the yearThe Week Recommends From Adolescence to Amandaland

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook