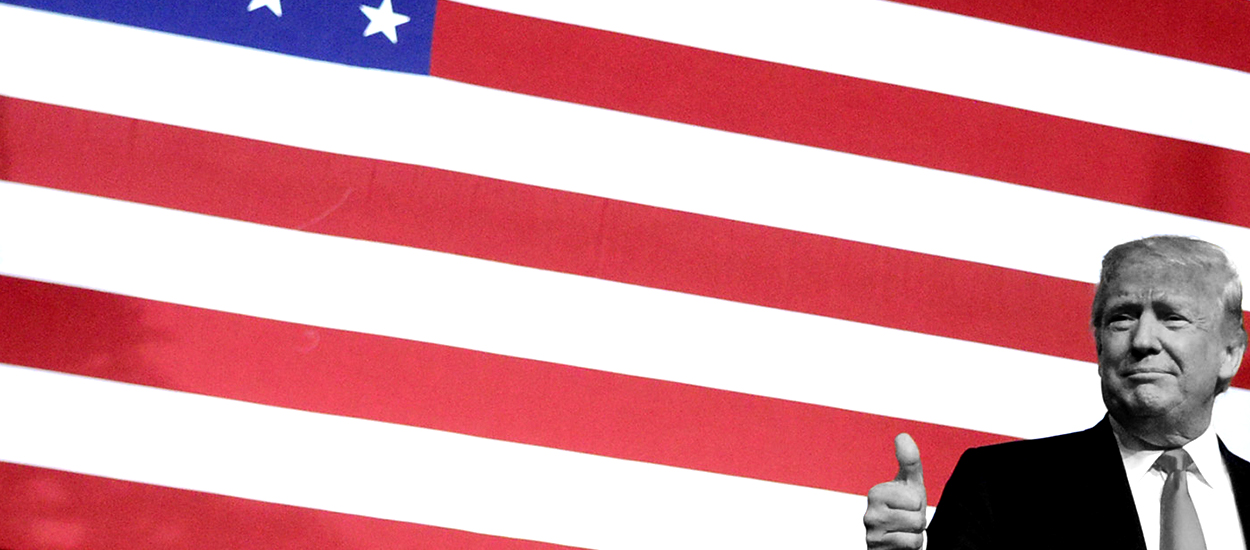

How Trump broke through the moralistic BS of American foreign policy

Trump doesn't care about foreign policy moralism. Good!

If journalist Jamal Khashoggi was in fact murdered by agents of the Saudi government, that would certainly be awful, a crime worth lamenting and condemning. But is it reasonable for the killing to inspire greater outrage and aggrievement than Saudi Arabia's multi-year bombardment of Yemen, which has killed of tens of thousands of civilians, with American backing, weapons, and logistical support?

That the single death of Khashoggi, tragic as it may be, has garnered far more coverage and provoked far greater indignation among members of the bipartisan foreign policy community and the journalists who report and comment on it does not speak well for anyone involved. On the contrary, it illustrates how the free-floating moralism that suffuses discussions about foreign policy in Washington easily produces paradoxical and even perverse judgments, with the mass suffering of multitudes shrugged off with a fraction of the concern accorded to single individuals.

Nothing would be better for America than for this moralism to be dissipated or dispelled — for the country to recover its capacity to think clearly and reasonably about its dealings with the wider world. It's in this one, limited respect that the presidency of Donald Trump, for all of the man's considerable faults, may well end up doing a bit of good — by forcing defenders of America's bipartisan foreign policy consensus to reflect critically on the foolishness that so often follows from their moralistic assumptions.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The president views international relations in transactional terms. Those who are most committed to a highly moralized version of American foreign policy find this offensive and like to describe it as amoral or even anti-moral. But the source of the objection isn't immediately obvious. In any transaction, one balances one's own good against those on the other side. The goal is gaining advantage for oneself. When an American president deals with the other nations of the world, we should hope and assume that he's doing so with the overriding aim of advancing the good of the United States.

Yet a significant segment of elite opinion in the United States is exceedingly uncomfortable with thinking in such self-interested terms. Instead, these opinion-makers believe the U.S. should think of itself as a moral actor using its military and economic power for noble ends. That sounds nice, and if the U.S. were an individual human being, it might well lead to acts of admirable, heroic self-sacrifice. But political communities are not individuals. Their elected leaders cannot escape the need to justify their actions on the world stage in terms of how they benefit the country — whose citizens fund and die in the wars the moralists so nobly justify.

This conflict between pursuing the good of the nation and the good of the world at large produces the moralistic muddle that is American foreign policy, with the U.S. constantly conflating what's good for itself with what's good for our allies with what's good for those in foreign countries suffering from poverty and oppression with what's good for the world as a whole. It was this muddle that convinced leading figures from both parties that overthrowing the government of Saddam Hussein would be a splendid idea for everyone concerned — for the U.S., for Israel, for the Iraqi people, for the Greater Middle East, and for global order more generally. This turned out to be wrong in just about every single respect.

Very similar, if less catastrophic, mistakes have led the U.S. to expend blood and treasure in Afghanistan for a stupefying 17 years and counting. They led Barack Obama to reproduce the errors of Iraq in Libya. They've led leading politicians and pundits to spend much of the last six years clamoring for the U.S. to intervene more forcefully in the Syrian civil war.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Over and over again the same arguments are made: Something bad is happening; we need to do something about it militarily; doing something about it is automatically in our interests, because our interests can't possibly clash with our values (or vice versa); if we fail to do something about it, then anything bad that transpires after our refusal to act can be attributed to our failure of nerve; and finally, if we act and things turn out badly (as they nearly always do), this is merely a product of faulty execution, which can and will be fixed the next time, and never a consequence of the overriding moral imperative (to do something) itself.

It is this string of faulty assumptions that Trump's amoral transactionalism promises to break.

Now, it's true that Trump could easily stumble into new wars due to incompetence. And there's no denying he's continued the wars he inherited; we're still in Afghanistan, and still funding Saudi Arabia's proxy war with Iran in Yemen. But so far, at least, there are no new Iraqs or Libyas on the horizon. And that's a very encouraging development.

For the first time in a very long time, the man occupying the Oval Office appears to be almost totally unmoved by moral appeals in dealing with the rest of the world. That understandably troubles many, and if it motivated him to launch wars of outright plunder (to "take the oil" perhaps), it would be a cause for serious concern and stringent opposition.

But the stark and troubling fact is that the U.S. has an extremely bad habit of starting wars (and spreading chaos and bloodshed) with the very best of moral intentions. If Trump can help us to break that habit, laying the foundations for a foreign policy grounded in greater realism and restraint, it will be a very good thing indeed.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred