Does deradicalisation work?

Government programmes under fire following London Bridge attack

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The effectiveness of government deradicalisation schemes is under intense scrutiny after two people were stabbed to death by a convicted terrorist at a prisoner rehabilitation event on Friday.

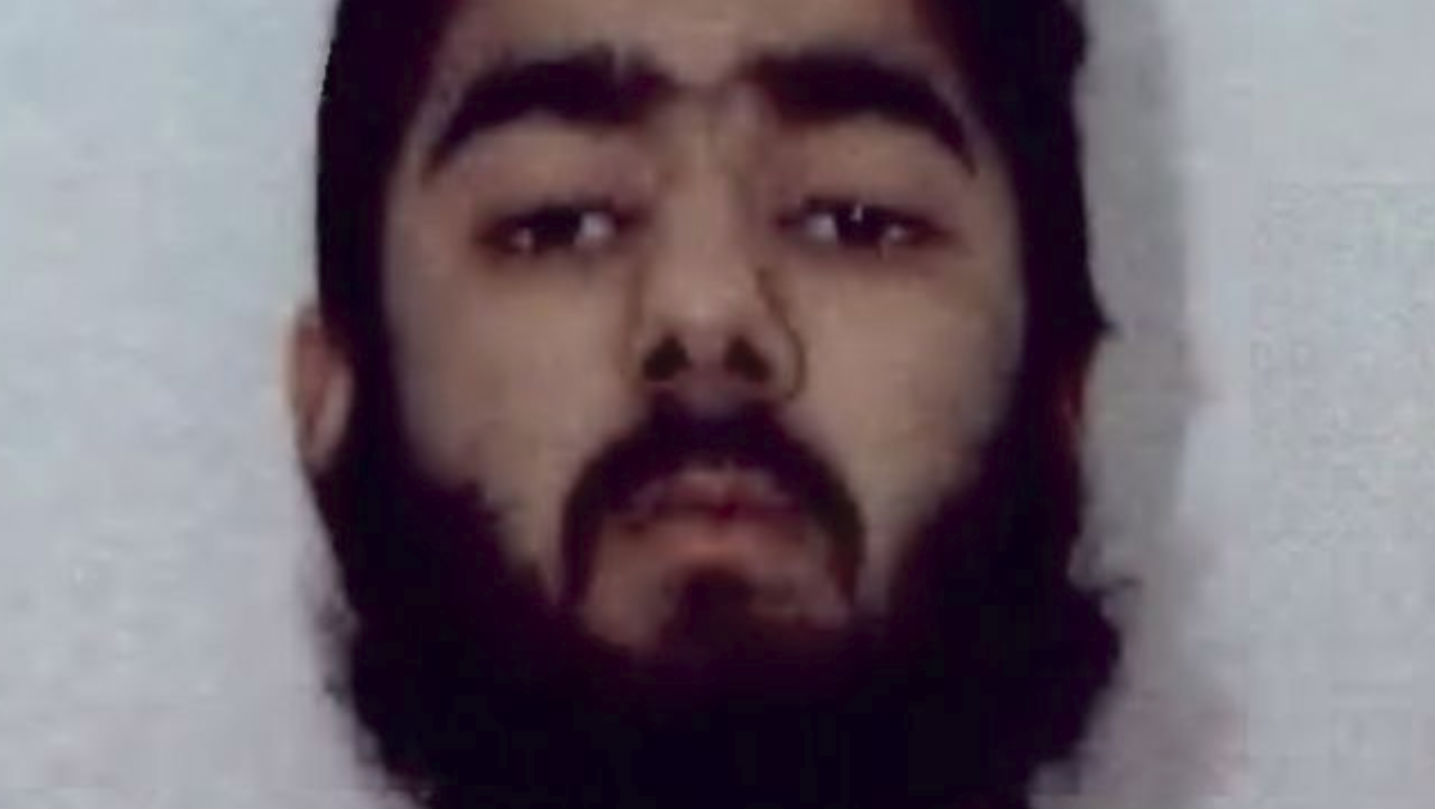

Usman Khan, a 28-year-old from Staffordshire, was shot dead by police on London Bridge after fatally attacking University of Cambridge graduates Jack Merritt, 25, and Saskia Jones, 23, and injuring three others.

The attack has triggered an urgent review of the licence conditions of convicted terrorists who have been released onto the streets of Britain.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The case of Usman Khan

Khan left prison in December 2018 after serving half of a 16-year sentence for his role in an al-Qa’eda-inspired plot to bomb the London Stock Exchange and establish a terrorist training camp.

He reportedly took part in a Healthy Identity Intervention course while in prison, and on release, had to sign up to the Desistance and Disengagement Programme (DPP). Both government schemes are designed to rehabilitate convicted terrorists or extremists.

According to the Home Office, support through the tailored DPP “could include mentoring, psychological support, theological and ideological advice”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Khan was also wearing a GPS tag to monitor his movements.

He is understood to have been given permission by the probation service to travel from the West Midlands to London on Friday to attend an event held by Learning Together. The programme, associated with the University of Cambridge’s Institute of Criminology, brings together people in criminal justice and higher education institutions to study alongside each other in order to help educate and rehabilitate prisoners.

Fake progress

The Ministry of Justice has admitted that there is “limited evidence of what assessments and interventions are the most effective for extremist offenders”, reports The Times.

Dr Rakib Ehsan, a research fellow at right-wing think-tank the Henry Jackson Society, argues that relying on deradicalisation courses, “however well-meaning, is insufficient”.

“If, as many believe, offenders simply fake progress to their counsellors, the scheme would be responsible for providing the public with false assurances as to the safety of jihadists released to live in ordinary British communities,” Ehsan told the newspaper.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––For a round-up of the most important stories from around the world - and a concise, refreshing and balanced take on the week’s news agenda - try The Week magazine. Start your trial subscription today –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Longer prison sentences?

Boris Johnson has pledged to introduce longer prison sentences for convicted terrorists if he wins the upcoming general election.

But the Financial Times says evidence from Northern Ireland suggests that “jail time can accelerate and intensify radicalisation”.

“The bigger issue is how to manage former terrorists both in prison and after their release,” the newspaper says.

Former prison governor Ian Acheson was tasked in 2015 with reviewing Islamist extremism in prisons for the government, and found what he describes as “serious deficiencies in almost every aspect of the management of terrorist offenders through the system”.

In an article printed in The Sunday Times yesterday, Acheson says he is “not sure any tangible progress has been made” since his review concluded, and calls for a “serious and sober review of the culture and capability of HM Prison and Probation Service to meet its primary role of keeping us safe from terrorism”.

But as The Guardian’s Alan Travis notes, “however long convicted terrorists are locked up, with the exception of a limited number of the most heinous cases, they are all going to have to be released eventually”.

He concludes: “The ‘lock ’em up and throw away the key’ battle cry may suit a panicked politician in the middle of a general election campaign, but it isn’t going to keep us safe from another Usman Khan.”

-

Political cartoons for February 9

Political cartoons for February 9Cartoons Monday's political cartoons include 100% of the 1%, vanishing jobs, and Trump in the Twilight Zone

-

Who is Starmer without McSweeney?

Who is Starmer without McSweeney?Today’s Big Question Now he has lost his ‘punch bag’ for Labour’s recent failings, the prime minister is in ‘full-blown survival mode’

-

Hotel Sacher Wien: Vienna’s grandest hotel is fit for royalty

Hotel Sacher Wien: Vienna’s grandest hotel is fit for royaltyThe Week Recommends The five-star birthplace of the famous Sachertorte chocolate cake is celebrating its 150th anniversary

-

How the ‘British FBI’ will work

How the ‘British FBI’ will workThe Explainer New National Police Service to focus on fighting terrorism, fraud and organised crime, freeing up local forces to tackle everyday offences

-

How the Bondi massacre unfolded

How the Bondi massacre unfoldedIn Depth Deadly terrorist attack during Hanukkah celebration in Sydney prompts review of Australia’s gun control laws and reckoning over global rise in antisemitism

-

Who is fuelling the flames of antisemitism in Australia?

Who is fuelling the flames of antisemitism in Australia?Today’s Big Question Deadly Bondi Beach attack the result of ‘permissive environment’ where warning signs were ‘too often left unchecked’

-

Ten years after Bataclan: how has France changed?

Ten years after Bataclan: how has France changed?Today's Big Question ‘Act of war’ by Islamist terrorists was a ‘shockingly direct challenge’ to Western morality

-

Arsonist who attacked Shapiro gets 25-50 years

Arsonist who attacked Shapiro gets 25-50 yearsSpeed Read Cody Balmer broke into the Pennsylvania governor’s mansion and tried to burn it down

-

Manchester synagogue attack: what do we know?

Manchester synagogue attack: what do we know?Today’s Big Question Two dead after car and stabbing attack on holiest day in Jewish year

-

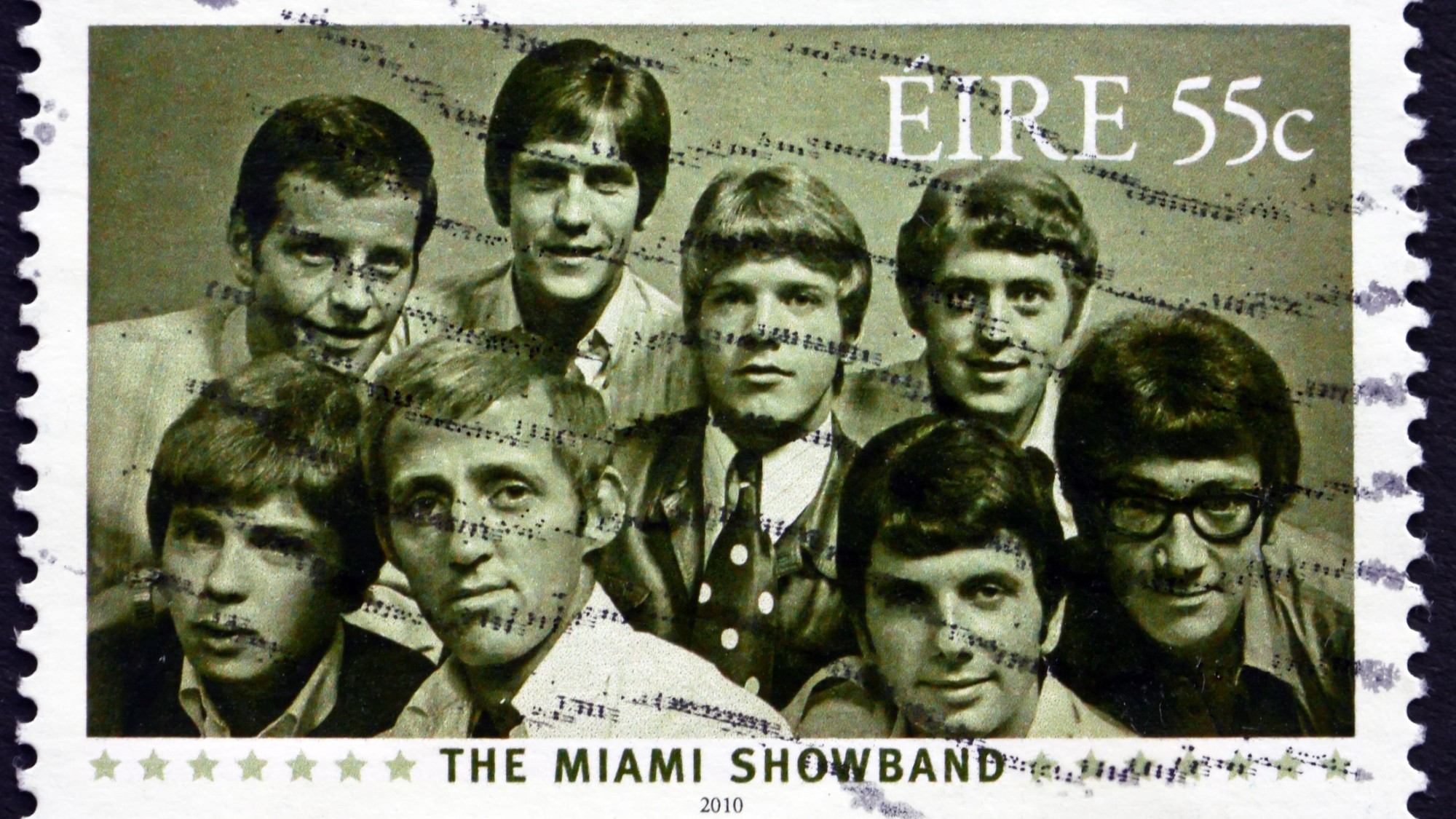

The Miami Showband massacre, 50 years on

The Miami Showband massacre, 50 years onThe Explainer Unanswered questions remain over Troubles terror attack that killed three members of one of Ireland's most popular music acts

-

Insects and sewer water: the alleged conditions at 'Alligator Alcatraz'

Insects and sewer water: the alleged conditions at 'Alligator Alcatraz'The Explainer Hundreds of immigrants with no criminal charges in the United States are being held at the Florida facility