What is cancel culture?

JK Rowling and Salman Rushdie condemn phenomenon of public shaming

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

JK Rowling, Margaret Atwood and Salman Rushdie are among more than 150 writers to sign an open letter denouncing “cancel culture”.

The term “cancel culture” refers to the phenomenon in which a person - usually a public figure - is boycotted because they have expressed an opinion that is perceived to be offensive.

The writer and academics who signed the letter say that it is a symptom of a society suffering from a weakened tolerance of different opinions in favour of “ideological conformity”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The signatories, who include Noam Chomsky, Malcolm Gladwell and Martin Amis, say that while figures like Donald Trump pose “a real threat to democracy”, resistance to that threat “must not be allowed to harden into its own brand of dogma or coercion”, reports Sky News.

What else does the letter say?

The letter, which was published on the website of Harper’s Magazine, says: “The free exchange of information and ideas, the lifeblood of a liberal society, is daily becoming more constricted.

“While we have come to expect this on the radical right, censoriousness is also spreading more widely in our culture: an intolerance of opposing views, a vogue for public shaming and ostracism, and the tendency to dissolve complex policy issues in a blinding moral certainty.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

“We uphold the value of robust and even caustic counter-speech from all quarters. But it is now all too common to hear calls for swift and severe retribution in response to perceived transgressions of speech and thought.

“This stifling atmosphere will ultimately harm the most vital causes of our time.

“The restriction of debate, whether by a repressive government or an intolerant society, invariably hurts those who lack power and makes everyone less capable of democratic participation.

“The way to defeat bad ideas is by exposure, argument, and persuasion, not by trying to silence or wish them away.”

What is cancel culture?

Anjana Susarla, associate professor of information systems at Michigan State University, offers a quick primer on The Conversation: “An individual or an organisation says, supports or promotes something that other people find offensive. They swarm, piling on the criticism via social media channels. Then that person or company is largely shunned, or ‘cancelled’.”

There are numerous examples: comedian and actor Kevin Hart withdrew from hosting the Oscars last year after it emerged that he had posted a series of homophobic tweets dating back to 2009; ABC abruptly cancelled Roseanne Barr’s TV show in 2018 after she posted a racist tweet; and Shane Gillis was dropped from Saturday Night Live last year after podcast footage showed him making a series of offensive comments.

Gemma Bath, from Australian women’s lifestyle website Mamamia, describes cancel culture as “an epidemic” and says “Caroline Flack was the latest casualty”. “Caroline was dragged into the modern day version of an archaic town square stoning in the months before she died,” says Bath.

Paul Blanchard, at City AM, agrees that her death shows that cancel culture “has to stop”. “Beneath the glamorous facade, people forget that celebrities are human too. Caroline, like others before her, became almost dehumanised by the Twitter lynch mobs who took so much pleasure from attacking her,” he says.

Where does the term come from?

Vox traces the phrase back to a quote in the 1991 film New Jack City, in which Wesley Snipes’s character dumps his girlfriend, saying “Cancel that bitch. I’ll buy another one.”

Lil Wayne references the quote in his 2010 song I’m Single, but Vox thinks the idea had its “first big boost into the zeitgeist” when a cast member on VH1’s reality show Love and Hip-Hop: New York tells his love interest: “You’re cancelled.”

It spread on Twitter and soon evolved into a disparaging response to celebrities. Early examples “contained the seeds of what cancel culture would become: a trend of communal calls to boycott a celebrity whose offensive behaviour is perceived as going too far”, says Vox.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––For a round-up of the most important stories from around the world - and a concise, refreshing and balanced take on the week’s news agenda - try The Week magazine. Start your trial subscription today –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Is it all bad?

Anne Charity Hudley, chair of linguistics of African America at the University of California, Santa Barbara, argues that the term has its roots in black culture and shouldn’t be dismissed.

“Cancelling is a way to acknowledge that you don’t have to have the power to change structural inequality,” she says. “You don’t even have to have the power to change all of public sentiment. But as an individual, you can still have power beyond measure.”

Last year, former US president Barack Obama appeared to weigh in, saying that being as “judgmental as possible about other people” is “not activism”. “If all you’re doing is casting stones, you’re probably not going to get that far,” he said, reports The Guardian.

In The New York Times, Ernest Owens responded that many millennials like himself use social media to “critique powerful people for promoting bigotry or harming others” as they don’t want them to have a “no-questions-asked platform to do this”.

“What members of older generations now dismiss as ‘cancel culture’ – or, as Mr. Obama put it, ‘being judgmental’ – is actually one of many modern-day iterations of protests they took part in when they were younger,” he says.

But, in the same newspaper, Loretta Ross says “there are better ways of doing social justice work”.

“Most public shaming is horizontal and done by those who believe they have greater integrity or more sophisticated analyses,” says Ross, adding that “call-outs are often louder and more vicious on the internet, amplified by the ‘clicktivist’ culture that provides anonymity for awful behaviour”.

She suggests replacing “calling-out” with what she coins “calling-in”, meaning engaging in debate “with words and actions of healing and restoration, and without the self-indulgence of drama”.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

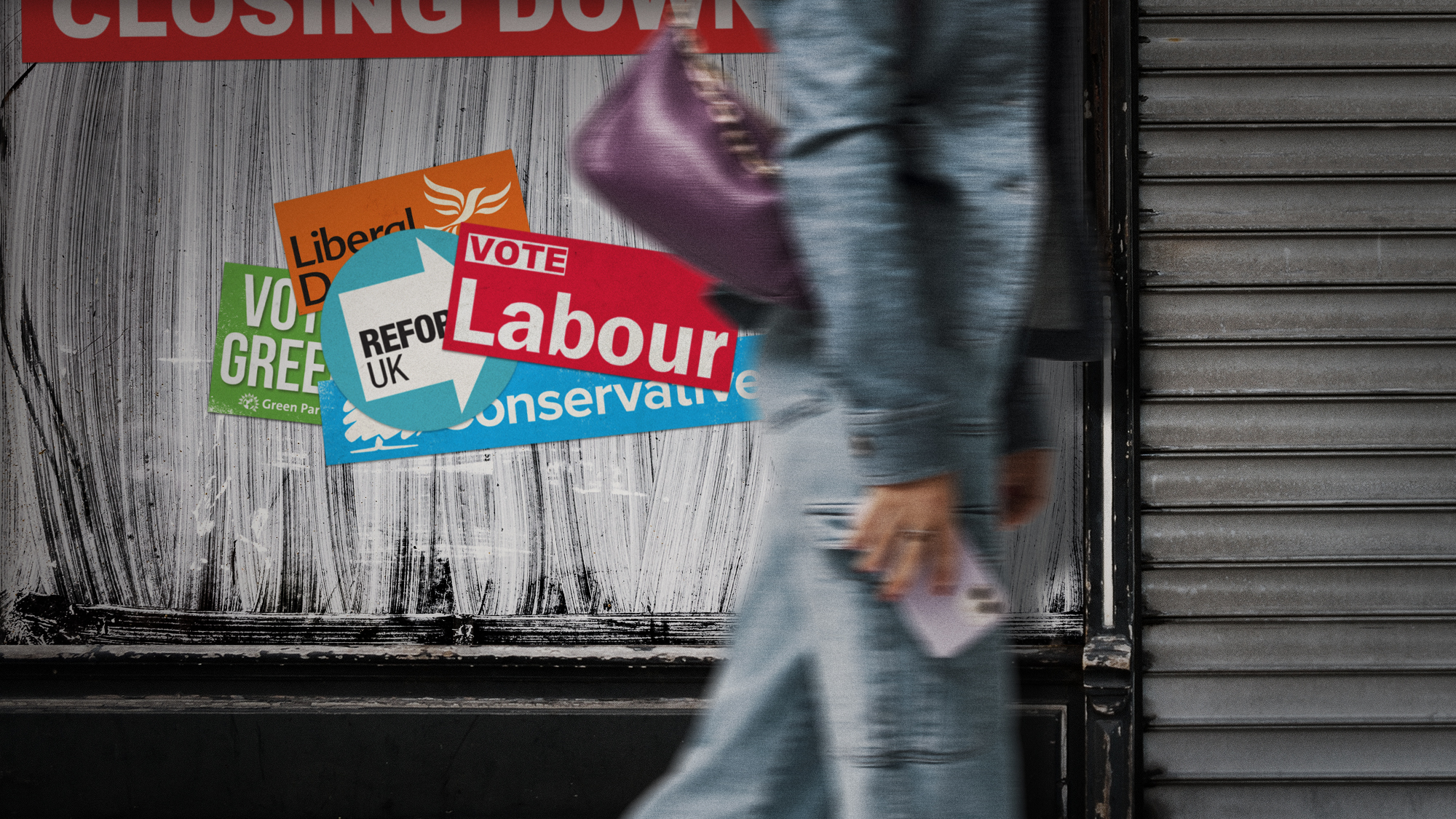

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

What is the Donroe Doctrine?

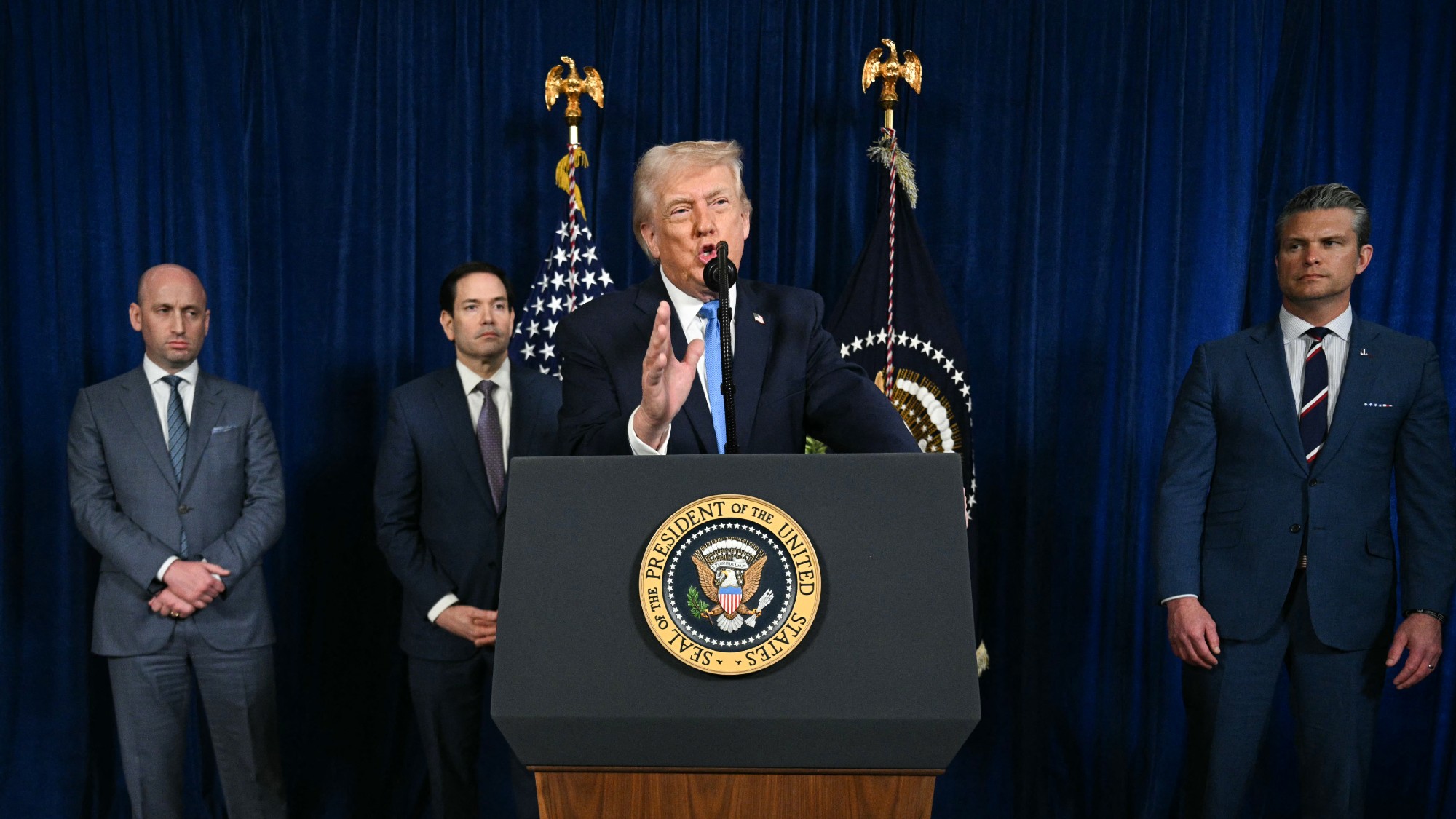

What is the Donroe Doctrine?The Explainer Donald Trump has taken a 19th century US foreign policy and turbocharged it

-

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?Today’s Big Question Nigel Farage’s party is ahead in the polls but still falls well short of a Commons majority, while Conservatives are still losing MPs to Reform

-

‘This estrangement from death has beget euphemisms’

‘This estrangement from death has beget euphemisms’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strong

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strongTalking Point Party is on track for a fifth consecutive victory in May’s Holyrood election, despite controversies and plummeting support

-

Will Trump actually prosecute Obama for 'treason'?

Will Trump actually prosecute Obama for 'treason'?Today's Big Question Or is this just a distraction from the Jeffrey Epstein scandal?

-

'Spending is what card issuers are hoping you will do'

'Spending is what card issuers are hoping you will do'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day