What is institutional racism?

Accusation leveled at Home Office in draft Windrush report

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

An early draft of the delayed Windrush review report branded the Home Office “institutionally racist” over the department’s “hostile environment” policy towards migrants, it has emerged.

The findings of the independent review into the deportation of Caribbean migrants who had lived legally in the UK for decades were originally due to be published in March last year but have yet to be made public.

However, The Times reports that inside sources say the phrase “institutionally racist” was included in an initial draft but no longer appears in more recent versions - triggering claims that the review report has been watered down.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What is institutional racism?

Institutional racism is a form of racism that exists in institutional settings, usually of a social or political nature.

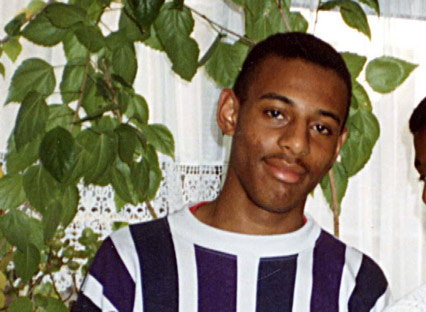

The Metropolitan Police force was famously branded “institutionally racist” in 1999 by Sir William Macpherson, who led the public inquiry into the fatal stabbing of black teenager Stephen Lawrence in 1993.

Macpherson defined institutional racism as “the collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture or ethnic origin”. This form of racism is seen in “processes, attitudes and behaviour which amount to discrimination through unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness and racist stereotyping which disadvantages minority ethnic people”, he said.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Two decades later, in 2018, a lawyer representing some of the families affected by the Grenfell Tower fire said the public inquiry into the June 2017 blaze should ask whether the tragedy, which claimed 72 deaths, was “a product of institutional racism”.

Others have claimed that institutional racism is also rife in the UK’s education system. In an article on The Conversation last year, Katy Sian, a lecturer in sociology at the University of York, wrote that “racism in British universities is endemic”.

An analysis of data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) showed that in 2012-13, of a total 17,880 professors in British universities, only 85 were black, 950 were Asian, and 365 were “other” (including mixed race).

Kalwant Bhopal, a Birmingham University professor of education and social justice, believes “white privilege” still dominates society, The Guardian reports.

She asks: “If the Race Relations Amendment Act (2000) and Macpherson were effective, why is it that if you are a black student you are less likely to leave university with a 2:1 or a first, less likely to attend an elite university and are more likely to be unemployed six months after graduation?”

Campaigners say that as well as being seen in education and policing, evidence for institutional racism has been found in housing, loans, immigration, the civil service, psychiatry and other medicine, and politics.

Bhopal claims that policymakers, employers and others in power only advance racial justice if it supports their own interests, creating “a smokescreen of conformity” with race equality agendas.

“We seem to be going round in circles,” she concludes.

Where did the concept originate?

The term “institutional racism” was first used publicly in 1967 by African-American civil rights activists Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture) and Charles V. Hamilton in their book Black Power: The Politics of Liberation, according to The Guardian’s Hugh Mair.

In the book, Carmichael and Hamilton contrasted “individual racism and institutional racism”. They described the latter as “less overt, far more subtle, less identifiable in terms of specific individuals committing the acts. But it is no less destructive of human life.”

Because institutional racism operates in “established and respected forces in society”, it receives “far less public condemnation”, the two campaigners argued.

“When white terrorists bomb a black church and kill five black children, that is an act of individual racism, widely deplored by most segments of the society,” they wrote.

“But when in that same city – Birmingham, Alabama – five hundred black babies die each year because of the lack of power, food, shelter and medical facilities, and thousands more are destroyed and maimed physically, emotionally and intellectually because of conditions of poverty and discrimination in the black community, that is a function of institutional racism.”

Ironically, in the UK, it was through the efforts of a white, public school-educated, knighted High Court judge that the spotlight was shone on the problem. When Macpherson branded the Met “institutionally racist”, he triggered change in British society that was “so significant, we have almost forgotten what it was like before”, according to Matthew Ryder QC.

“The notion that there was a structural component to racism that is more impactful than personal animus or hostility is now well established,” says Ryder, who served as London’s deputy mayor for integration until last year. “That was almost a completely alien concept before the Stephen Lawrence inquiry happened.”

The public denouncement of the Met empowered black people to hold institutions to account for racism, Ryder argues.

Any critics of the phrase?

The term “institutional racism” has been described as “incendiary” by Trevor Philips, former chair of the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC), reports the BBC.

In a 2009 speech marking ten years since the Lawrence murder report in which Macpherson used the phrase, Philips said that Britain was “by far the best place in Europe to live if you are not white”.

“The use of the term was incendiary,” he said. ‘It rocked the foundations of the police service and caused widespread anguish in government.”

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military