Will coronavirus signal the end of the handshake?

Leading immunologists call for end to traditional greeting, but millennia-old custom could be hard to shake

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The handshake could become one of many long-term cultural casualties of the coronavirus pandemic, which looks set to forever change how humans physically interact.

Earlier this month, Anthony Fauci, the US’s chief immunologist, told the Wall Street Journal that: “As a society, just forget about shaking hands, we don't need to shake hands. We’ve gotta break that custom, because as a matter of fact that is really one of the major ways you can transmit a respiratory-borne illness”.

“I don’t think we should ever shake hands ever again, to be honest with you” he said.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

“If Fauci’s advice were to be taken en masse, it would mark a profound shift in human behaviour,” says the BBC. “After all, shaking hands has been the de facto greeting in international business, politics and society for the better part of a century. Its origins go back millennia.”

Yet “Fauci isn’t alone in his opinion of handshaking,” says CNBC.

Gregory Poland, director of the Mayo Clinic Vaccine Research Group and spokesperson for Infectious Diseases Society of America, told the news network he been trying to put an end to handshakes for nearly three decades.

“It’s an outdated custom,” he says. “Many cultures have learned that you can greet one another without touching each other.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As the virus took hold around the world in March, The Guardian reported how different countries and cultures were changing their greeting habits.

Bumping elbows is one gesture that is becoming common. In China, loudspeakers told people to make the traditional gong shou gesture, a fist in the opposite palm, to say hello, while in Australia, Brad Hazzard, the New South Wales health minister, advised people to instead give each other a pat on the back. In Iran, it has become common for friends meeting to keep their hands in their pockets and tap their feet against each other as a greeting.

Another alternative suggested by Poland is tilting or bowing your head to greet another person. “When men greeted other people [back in the day], they raised tor tipped their hat,” he says.

There is even a Linkedln page calling for the end of the handshake.

“We’re likely to see a recalibration of the bubble of personal space we keep around ourselves—a field scientists call proxemics,” says Wired. “This varies across cultures already—North Americans and Europeans tend to leave more space around each other than people from Asia, for example”. But anthropologist Sheryl Hamilton of Carleton University in Ottawa told the technology magazine this “might end up breaking along class lines rather than cultural ones in an era of more frequent epidemics, with rich people sequestering themselves away in private cars and spacious high-end restaurants to an even greater extent, while the rest of us travel by cramped public transport”.

Yet, coming automatically to many of us, “refraining from such a common behaviour” as a handshake “is easier said than done”, writes performance academic Erika Hughes in The Conversation.

It has “long been understood as a gesture that establishes a positive connection between two people”, she says, and “at least in the realm of politics, shaking hands is seen as fundamental to how elected officials signal their connection to the average Joe”, CNN reports.

“What the handshake is saying is, ‘I'm really with you and here for you. You can trust me,’” handshake expert Robert Brown told the Chicago Tribune in 2005.

US President Donald Trump suggested as much when he told a Fox News town hall in early March “you can't be a politician and not shake hands.”

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––For a round-up of the most important stories from around the world - and a concise, refreshing and balanced take on the week’s news agenda - try The Week magazine. Start your trial subscription today –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

The stalled fight against HIV

The stalled fight against HIVThe Explainer Scientific advances offer hopes of a cure but ‘devastating’ foreign aid cuts leave countries battling Aids without funds

-

Obesity drugs: Will Trump’s plan lower costs?

Obesity drugs: Will Trump’s plan lower costs?Feature Even $149 a month, the advertised price for a starting dose of a still-in-development GLP-1 pill on TrumpRx, will be too big a burden for the many Americans ‘struggling to afford groceries’

-

Can TrumpRx really lower drug prices?

Can TrumpRx really lower drug prices?Today’s Big Question Pfizer’s deal with Trump sent drugmaker stocks higher

-

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the rise

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the riseThe Explainer ‘No evidence’ new variant is more dangerous or that vaccines won’t work against it, say UK health experts

-

Why are autism rates increasing?

Why are autism rates increasing?The Explainer Medical experts condemn Trump administration’s claim that paracetamol during pregnancy is linked to rising rates of neurodevelopmental disorder in US and UK

-

Trump seeks to cut drug prices via executive order

Trump seeks to cut drug prices via executive orderspeed read The president's order tells pharmaceutical companies to lower prescription drug prices, but it will likely be thrown out by the courts

-

How Trump's executive orders are threatening scientific research

How Trump's executive orders are threatening scientific researchIn the spotlight Agencies are purging important health information

-

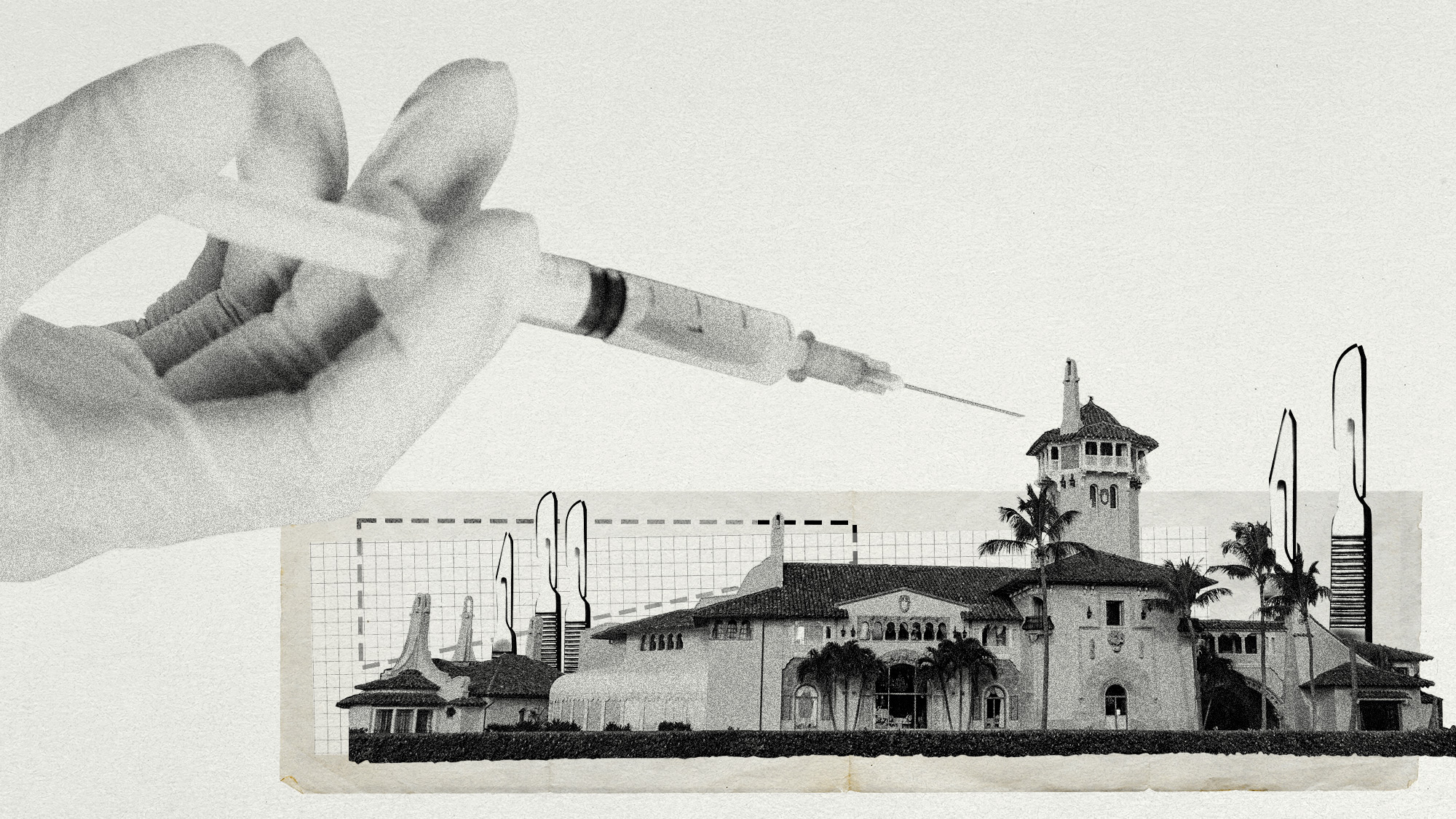

Mar-a-Lago face: has Maga plastic surgery trend peaked?

Mar-a-Lago face: has Maga plastic surgery trend peaked?Under the Radar The must-have look for Trump’s inner circle does not come easy – or cheap – but it may be starting to fall out of favour