Why did UK take so long to introduce quarantining - and does it work?

Government to introduce mandatory 14-day self-isolation for new arrivals to Britain

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The UK is set to join the growing number of countries that have introduced quarantine rules for people arriving from abroad - but critics are asking why Boris Johnson’s government waited so long.

Brussels-based news site EUobserver reported in March that nine European Union states had closed their borders entirely, and Germany - which has been lauded for its coronavirus response - has had quarantine measures in place since early April.

The UK quarantine is due to kick in next month and will extend “to all arrivals into the UK with a number of exemptions, reportedly including hauliers and Covid-19 research scientists”, according to The Guardian.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Transport Secretary Grant Shapps is also backing proposals for so-called “air bridges” exempting travellers returning from countries with low coronavirus infection rates. For everyone else, however, quarantining is about to become the new normal.

How does quarantining work?

Quarantines are widely regarded as an effective tool in the fight against infectious diseases such as the new coronavirus. They work by keeping people who might become infected, or who might infect others, away from one another.

Isolation is related but is slightly different. “While isolation serves the same purpose as quarantine, it’s reserved for those who are already sick. It keeps infected people away from healthy people to prevent the sickness from spreading,” explains the website of the Ohio-based Cleveland Clinic research centre.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Government mandate quarantines are when countries or federal states put legal restrictions on movement, forcing people to stay in one place.

The UK plans to introduce a compulsory two-week quarantine period for new arrivals to the country from early June.

Downing Street is waiting for a sustained drop in the UK’s “R value” - the average number of people that one infected person will go on to infect - before it introduces the mandatory quarantine for new visitors.

Why does the R value matter?

“The reason we’re interested is because it not only gives you an idea of how many people the virus is likely to infect, but also an idea about how effective your interventions need to be to end the outbreak,” Jonathan Ball, professor of molecular virology at the University of Nottingham, told The Telegraph.

The unchecked R value of the new coronavirus is around 3, but the UK has currently surpressed this infection rate to between 0.7 and 1.

“If the reproduction number is higher than 1 then the number of cases increases exponentially - it snowballs like debt on an unpaid credit card,” explains the BBC’s science correspondent James Gallagher. “But if the number is lower, the disease will eventually peter out, as not enough new people are being infected to sustain the outbreak.”

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––For a round-up of the most important stories from around the world - and a concise, refreshing and balanced take on the week’s news agenda - try The Week magazine. Start your trial subscription today –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

What has the UK waited to act?

“To prevent reinfection from abroad, I am serving notice that it will soon be the time – with transmission significantly lower – to impose quarantine on people coming into this country by air,” the prime minister announced during a televised address on 10 May.

However, why the UK has waited until now to do so remains unclear.

Speaking anonymously to The Guardian, a senior government adviser said: “There was really no scientific advice to inform the latest announcement. It also doesn’t really make sense for countries which have lower per capita current Covid case numbers than us - for example, most of the EU.

“That sort of policy only reduces risk in the situation where we have very low case numbers and origin countries have much higher numbers.”

Up until 13 March, Johnson’s government advised that incoming passengers from specific countries with a high number of infections, including Italy, Iran and parts of China, should self-isolate. But this guidance was dropped – “inexplicably”, according to Labour MP Yvette Cooper, chair of the Home Affairs Select Committee.

Professor Gary McLean, a professor in molecular immunology at London Metropolitan University, told The Guardian that the plans for new border measures “don’t make logical sense”, adding: “In all reality, they should’ve done this two months ago, not now.”

A spokesperson for the PM said the government’s approach “is, and always has been, driven by the latest scientific and medical advice”.

But Downing Street has not published the scientific advice behind its decision to first leave borders open and now start controlling them.

A letter signed by the chief executives of easyJet, Heathrow and Gatwick that was sent to the government last week voiced “collective and serious concern and frustration” over the planned new measures, adding: “An open-ended quarantine, with no set end date, will make an already critical situation for UK aviation, and all the businesses we support, even worse.”

Seemingly the only light at the end of the tunnel for airlines in the new air bridges proposal, “which would see agreements sought with countries with low R numbers... to let passengers travel between them without going into quarantine”, says Sky News.

-

Sepsis ‘breakthrough’: the world’s first targeted treatment?

Sepsis ‘breakthrough’: the world’s first targeted treatment?The Explainer New drug could reverse effects of sepsis, rather than trying to treat infection with antibiotics

-

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek star

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek starIn The Spotlight Van Der Beek fronted one of the most successful teen dramas of the 90s – but his Dawson fame proved a double-edged sword

-

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?Today's Big Question The King has distanced the Royal Family from his disgraced brother but a ‘fit of revolutionary disgust’ could still wipe them out

-

El Paso airspace closure tied to FAA-Pentagon standoff

El Paso airspace closure tied to FAA-Pentagon standoffSpeed Read The closure in the Texas border city stemmed from disagreements between the Federal Aviation Administration and Pentagon officials over drone-related tests

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

‘Implementing strengthened provisions help advance aviation safety’

‘Implementing strengthened provisions help advance aviation safety’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

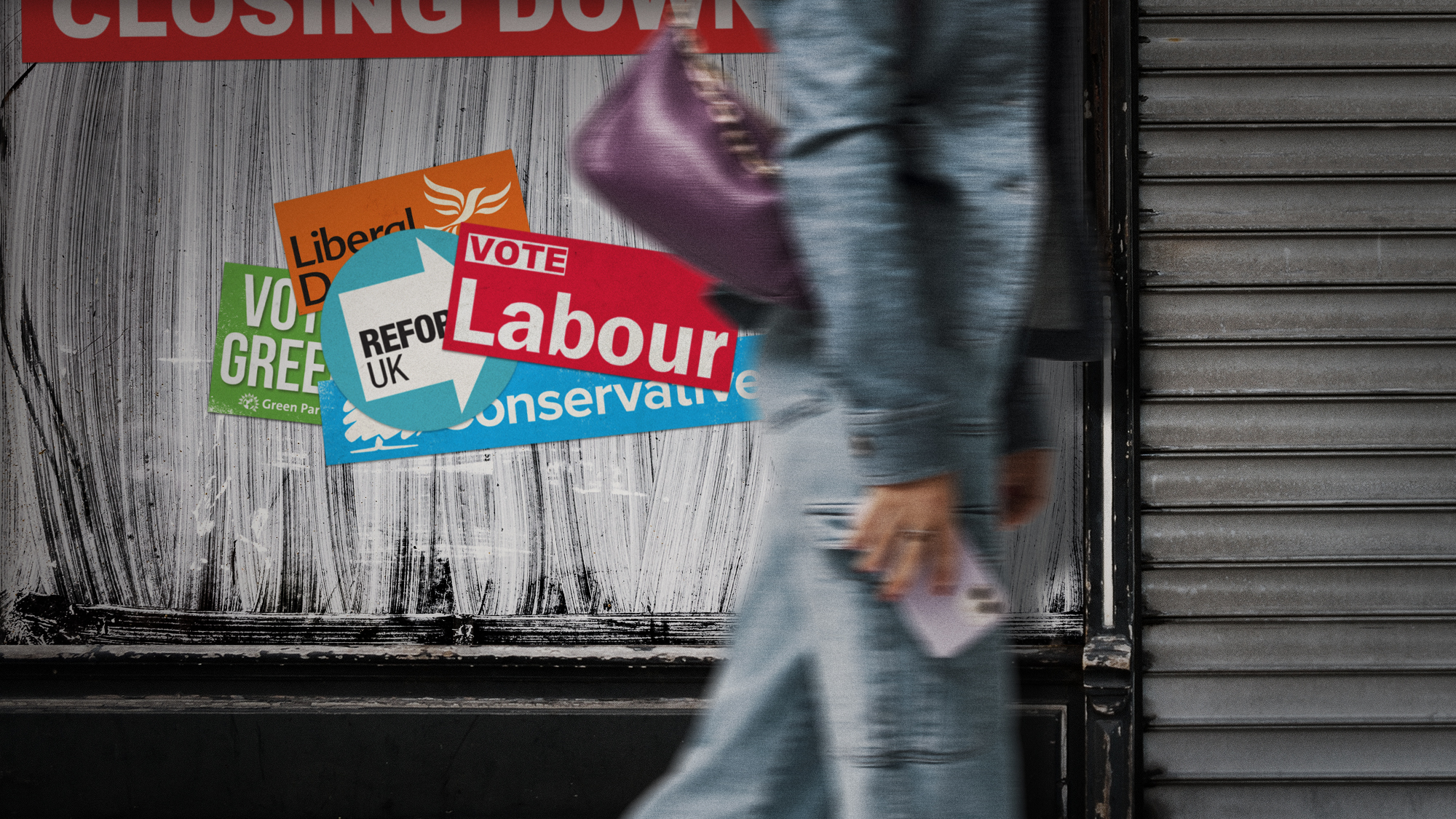

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?Today’s Big Question Nigel Farage’s party is ahead in the polls but still falls well short of a Commons majority, while Conservatives are still losing MPs to Reform

-

FAA to cut air travel as record shutdown rolls on

FAA to cut air travel as record shutdown rolls onSpeed Read Up to 40 airports will be affected

-

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strong

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strongTalking Point Party is on track for a fifth consecutive victory in May’s Holyrood election, despite controversies and plummeting support

-

Could air traffic controllers help end the government shutdown?

Could air traffic controllers help end the government shutdown?Today’s Big Question The controllers were crucial in ending the last shutdown in 2019