52 ideas that changed the world - 30. The production line

Pioneered by Henry Ford, the assembly line heralded the birth of mass production

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In this series, The Week looks at the ideas and innovations that permanently changed the way we see the world. This week, the spotlight is on the production line:

The production line in 60 seconds

A production line (or assembly line) is a sequential set of procedures, most commonly taking place in a factory, that leads to the completed production of an object.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The object normally moves from workstation to workstation, with different people or machines adding parts. Production lines are often used to assemble complex items, for example cars, household appliances and electronic goods.

The idea behind a production line is that it improves efficiency by reducing the movement of parts and people as much as possible.

According to American automobile magnate Henry Ford, whose factories popularised a production line-style of manufacturing in the early 1900s, a production line should do three things:

- “Place the tools and the men in the sequence of the operation so that each component part shall travel the least possible distance while in the process of finishing.”

- “Use work slides or some other form of carrier so that when a workman completes his operation, he drops the part always in the same place… and if possible have gravity carry the part to the next workman for his own.”

- “Use sliding assembling lines by which the parts to be assembled are delivered at convenient distances.”

Ford pioneered the system of production and, according to history.com, broke the production of his famous Ford Model T’s “into 84 discrete steps”. Each of his workers was trained to do just one of these steps.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How did it develop?

The production line was unheard of in the Western world prior to the Industrial Revolution, when most products were made by a single craftsman or artisan, according to historycrunch.com.

History.net notes that by 1500 the “arsenal” in Venice had become “the nerve centre of the Venetian state and the largest industrial complex in the world”. The shipyard-cum-armoury “employed production methods of unparalleled efficiency that long predated Henry Ford”. These includes assembly lines and the use of standardised parts.

The production line became more popular with the arrival of mechanised workplaces. In 1785, American engineer Oliver Evans invented the automatic flour mill, while in 1802 Marc Brunel, father of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, designed what the BBC calls “the first example of the use of all metal machine tools for mass production”.

As The History Press notes, Brunel’s steam-powered machines manufactured wooden pulley blocks for Royal Navy ships to handle guns and rigging.

According to the research paper Science and Technology in the Industrial Revolution, these early experiments with efficient production inspired the Bridgewater Foundry in Manchester, which was founded in 1836.

Bordered by the Bridgewater Canal and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, the factory buildings were arranged in a line with a railway for carrying the work going through the buildings. Cranes were also employed for lifting the heavy work, mirroring the future use of forklift trucks in modern factories.

By the end of the 19th century, one of the most influential assembly lines in history was in operation: the Chicago slaughterhouse line. The car manufacturer Henry Ford wrote that the production lines used in the Chicago meat slaughtering and packaging industries influenced his own famous factories.

Starting in 1867, workers in Chicago would stand at fixed stations and an overhead rail system would bring the meat to each worker, notes The Guardian.

“Every piece of work in the shop moves; it may move on hooks, on overhead chains… it may travel on a moving platform, or it may go by gravity, but the point is that there is no lifting or trucking,” Ford wrote.

The slaughterhouses inspired Ford’s 1913 installation of the first moving assembly line for the mass production of an entire car. According to history.com: “His innovation reduced the time it took to build a car from more than 12 hours to two hours and 30 minutes.”

As part of the drive to improve efficiency, Ford “also hired motion-study expert Frederick Taylor to make those jobs even more efficient”, while building “machines that could stamp out parts automatically”, the history website adds.

The Second World War made mass production in the Western world all the more vital. William S. Knudsen, a former employee of Ford, would later observe that the US was important to the war effort because it “smothered the enemy in an avalanche of production, the like of which he had never seen, nor dreamed possible”.

An example of this was the mass production of aeroplanes for the war effort. According to Dana Parker's 2013 book Building Victory, US aircraft manufacturers built more than 300,000 planes for the military during the Second World War, having produced fewer than 3,000 in 1939. The Vultee Aircraft Corporation was responsible for many of these, pioneering the use of the powered assembly line for aircraft manufacturing in the process.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, engineers around the world experimented with robotics as a means of boosting industrial development. Robotics.org reports that General Motors installed its own robotic arm to assist in the assembly line in 1961. This set the precedent for the increasing motorisation of production lines during the late 20th century.

That said, the increasing use of mechanisation does not mean that people no longer work directly on production lines in the 21st century. Huge multinational corporations such as Amazon have come under fire for mistreating workers on their production lines, with The Guardian reporting that employees in China “get no sick pay or holiday pay and can be laid off without any pay at all during quiet months when production drops off”.

Half of the world’s iPhones are made at a factory complex in Zhengzhou, China, reports Business Insider. The complex employs as many as 350,000 people on assembly lines. So vast is the production operation that locals have begun describing the site as “iPhone City”.

How did it change the world?

The production line had such a profound effect on industrial businesses that those who did not adopt the practice were quickly forced to close.

The process was far more efficient, saving time and money for businesses. It had a dramatic impact on production and society, and was crucial to the US war effort in the Second World War.

The efficiencies of mass production meant US firms could switch from making consumer goods to war goods quickly, and could produce armaments at speed.

Henry Ford argued that the assembly line improved working conditions for staff because it reduced the amount of heavy lifting, stooping and bending that was required.

He also removed the need for special training. This was a double-edged sword for workers, who saw their value fall as a result of the new system.

Ford also found that by making the production of cars so much quicker, costs of buying new automobiles began to plummet, and they became much more accessible to the average buyer. The Model T had cost $850 in 1908 but that dropped to less than $300 by 1925, says Encyclopaedia Britannica.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 52. Zero

52 ideas that changed the world - 52. ZeroIn Depth The technology on which you’re reading this article only works because of zero

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 50. Money

52 ideas that changed the world - 50. MoneyIn Depth Millennia of civilisations have used mediums of exchange ranging from seashells and cows to bitcoin and cash

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 49. Ecology

52 ideas that changed the world - 49. EcologyIn Depth Scientific ecology can be traced back to Charles Darwin and considers living things and their environment

-

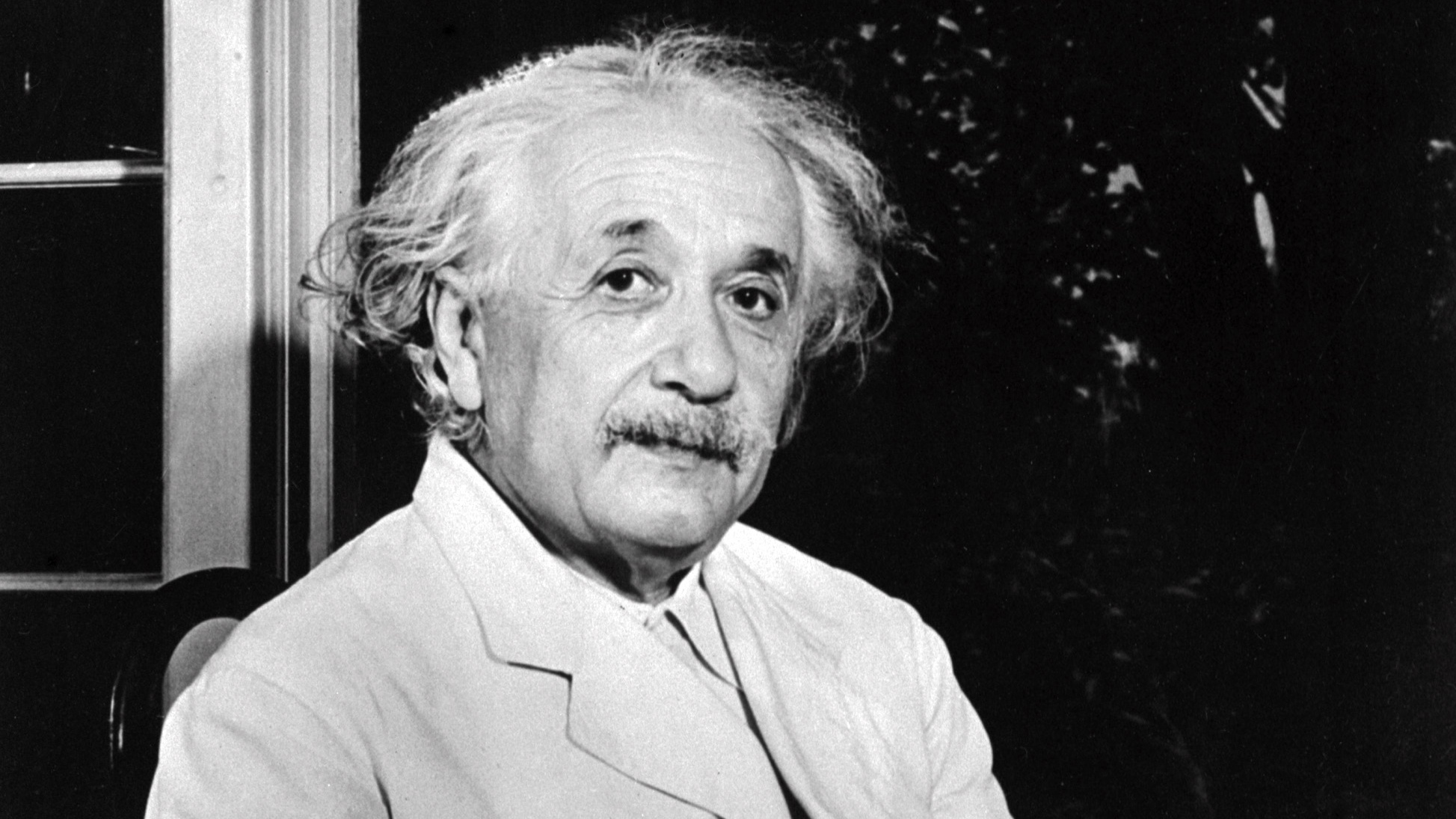

52 ideas that changed the world - 47. Relativity

52 ideas that changed the world - 47. RelativityIn Depth Einstein’s theory remains ‘most important in modern physics’

-

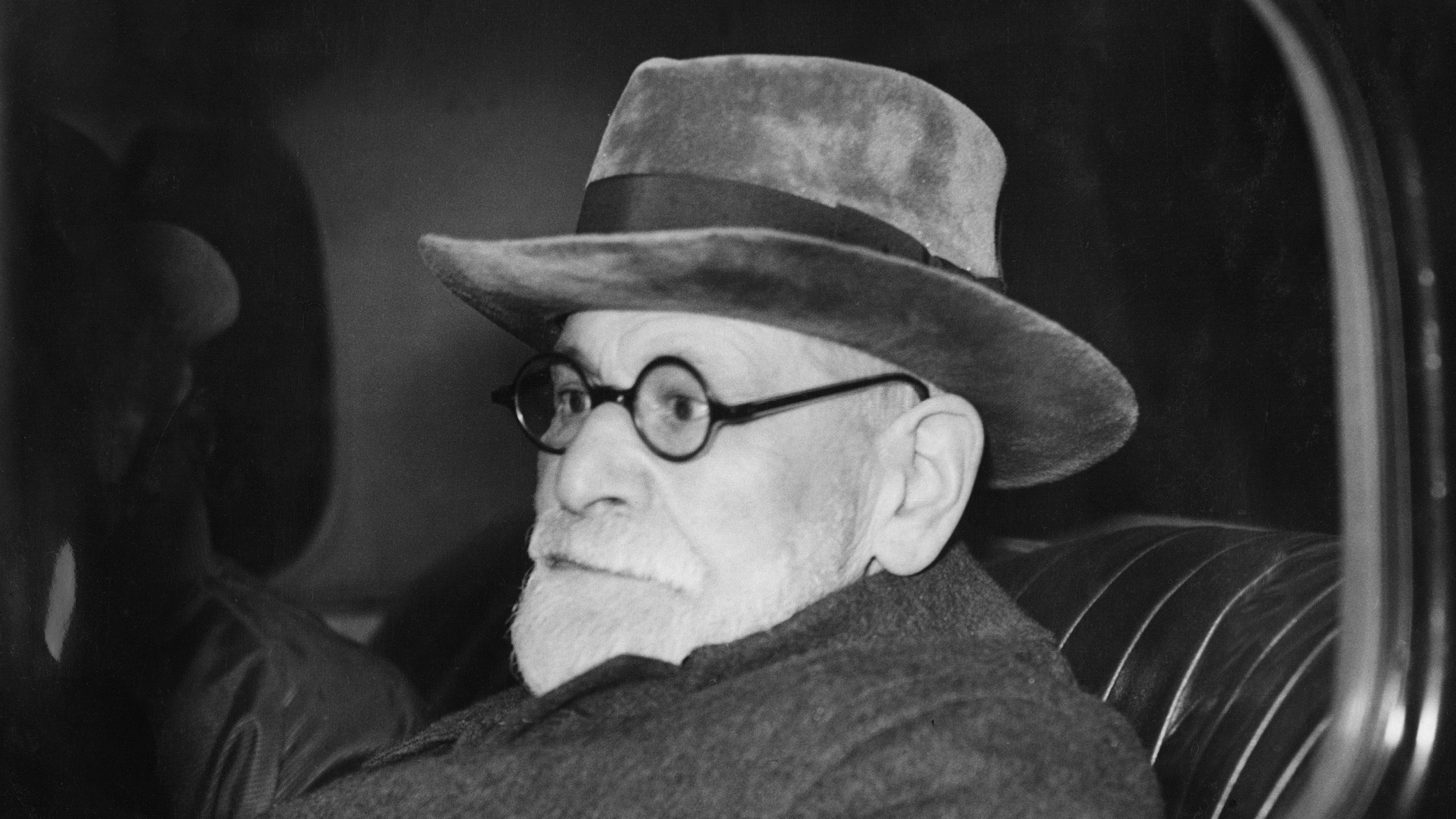

52 ideas that changed the world - 46. The unconscious mind

52 ideas that changed the world - 46. The unconscious mindIn Depth The theory of an obscured section of human consciousness has hooked psychologists for centuries

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 43. Writing

52 ideas that changed the world - 43. WritingIn Depth Writing is the foundation of history, great literature – and this article

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 42. Monogamy

52 ideas that changed the world - 42. MonogamyIn Depth The roots of monogamy have more to do with evolution than romance

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 41. The wheel

52 ideas that changed the world - 41. The wheelIn Depth The wheel might seem simple, but it took humans a long time to figure it out