World’s first genetically altered babies born in China

If true, breakthrough ‘would be profound leap of science and ethics’ despite condemnation from medical profession

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

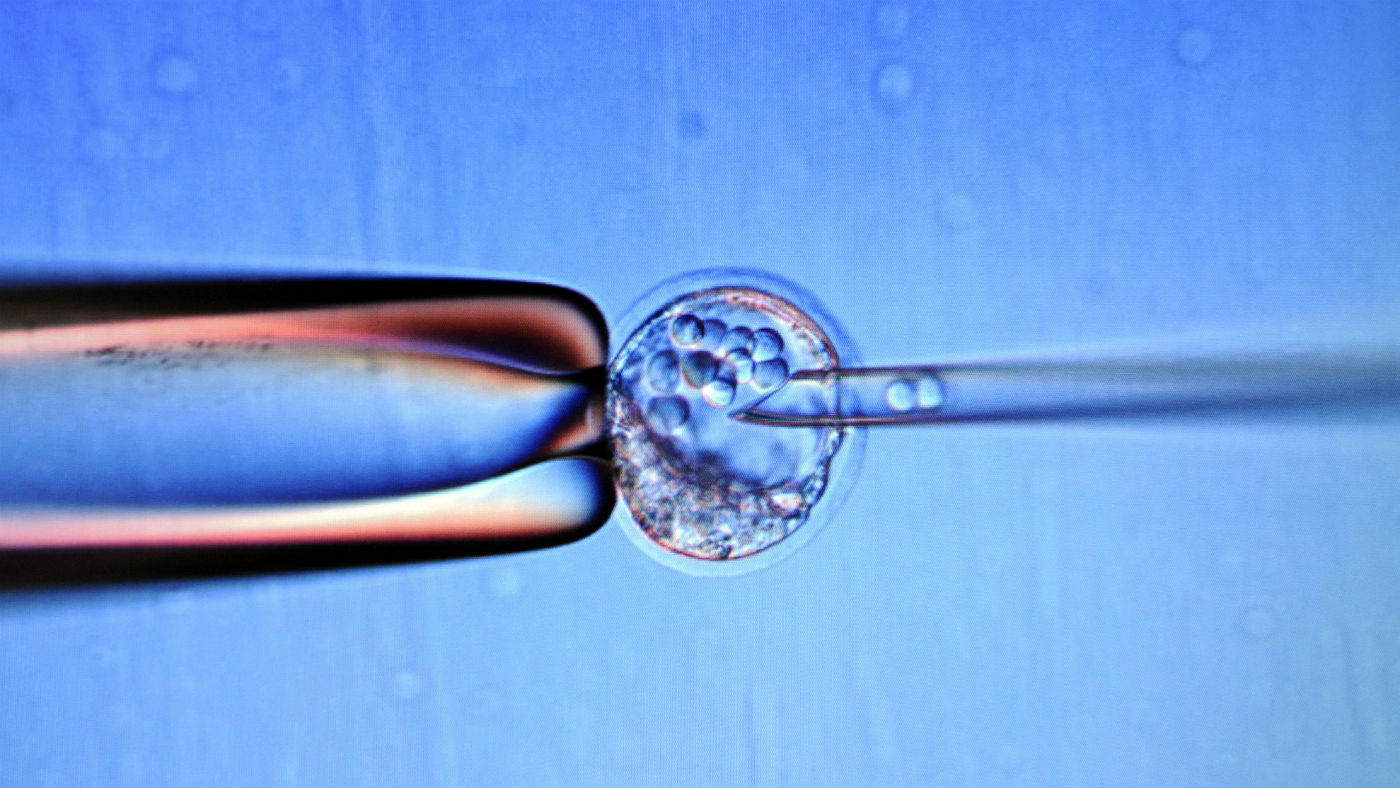

A Chinese scientist claims to have created the world’s first genetically altered babies, in a potentially groundbreaking first that has drawn widespread condemnation from the medical community.

He Jiankui of Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, says he altered embryos for seven couples during fertility treatments, with one successful pregnancy resulting in twin girls that the scientist claims are naturally resistant to HIV.

The Guardian says “if true, it would be a profound leap of science and ethics”. This kind of gene editing is banned in most countries over fears the technology is not far enough developed and DNA changes can pass to future generations with unintended long-term consequences.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The birth of the first genetically tailored humans “would be a stunning medical achievement, for both He and China” says the MIT Technology Review which first broke the story. “But it will prove controversial, too. Where some see a new form of medicine that eliminates genetic disease, others see a slippery slope to enhancements, designer babies, and a new form of eugenics.”

Polls in the US and China have consistently shown a majority of citizens support gene editing but many mainstream scientists think it is still ethically suspect and too unsafe to try, and some have denounced the experiment as “monstrous” human experimentation, reports The Independent.

Dr Kiran Musunuru, a University of Pennsylvania gene editing expert and editor of a genetics journal, described the claim as “unconscionable... an experiment on human beings that is not morally or ethically defensible”.

“This is far too premature,” Dr Eric Topol, who heads the Scripps Research Translational Institute in California, told the Daily Telegraph. “We're dealing with the operating instructions of a human being. It's a big deal.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There are also questions about He’s professional practice. There is no independent confirmation of his claim, and it has not been published in a journal, where it would be vetted by other experts. It is unclear whether he properly explained the purpose and potential risks to participants in the trial.

However, speaking exclusively to the Associated Press ahead of an international conference on gene editing that gets underway in Hong Kong today, He defended his work.

“I feel a strong responsibility that it’s not just to make a first, but also make it an example. Society will decide what to do next” in terms of allowing or forbidding such science.

Whatever the ultimate conclusions, some have argued He’s experiments should serve as a warning of what is to come.

“It was inevitable that someone trying to reach the limelight would likely try this. However it is often better to be safe than to be first,” said Professor Peter Braude, a reproductive health specialist at King’s College London.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Pros and cons of gene-editing babies

Pros and cons of gene-editing babiesPros and Cons Controversial scientist says he feels “unease” about the future of children whose genes he edited as embryos

-

Home Office worker accused of spiking mistress’s drink with abortion drug

Home Office worker accused of spiking mistress’s drink with abortion drugSpeed Read Darren Burke had failed to convince his girlfriend to terminate pregnancy

-

In hock to Moscow: exploring Germany’s woeful energy policy

In hock to Moscow: exploring Germany’s woeful energy policySpeed Read Don’t expect Berlin to wean itself off Russian gas any time soon

-

Were Covid restrictions dropped too soon?

Were Covid restrictions dropped too soon?Speed Read ‘Living with Covid’ is already proving problematic – just look at the travel chaos this week

-

Inclusive Britain: a new strategy for tackling racism in the UK

Inclusive Britain: a new strategy for tackling racism in the UKSpeed Read Government has revealed action plan setting out 74 steps that ministers will take

-

Sandy Hook families vs. Remington: a small victory over the gunmakers

Sandy Hook families vs. Remington: a small victory over the gunmakersSpeed Read Last week the families settled a lawsuit for $73m against the manufacturer

-

Farmers vs. walkers: the battle over ‘Britain’s green and pleasant land’

Farmers vs. walkers: the battle over ‘Britain’s green and pleasant land’Speed Read Updated Countryside Code tells farmers: ‘be nice, say hello, share the space’

-

Motherhood: why are we putting it off?

Motherhood: why are we putting it off?Speed Read Stats show around 50% of women in England and Wales now don’t have children by 30