The myopic folly of demanding a new constitutional convention

Our government often seems bumbling, corrupt, and wasteful. But it could be worse. Much worse.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Americans have a thing for starting over. We love the idea of breaking from the past, beginning from scratch, getting a new life, setting out on a fresh path.

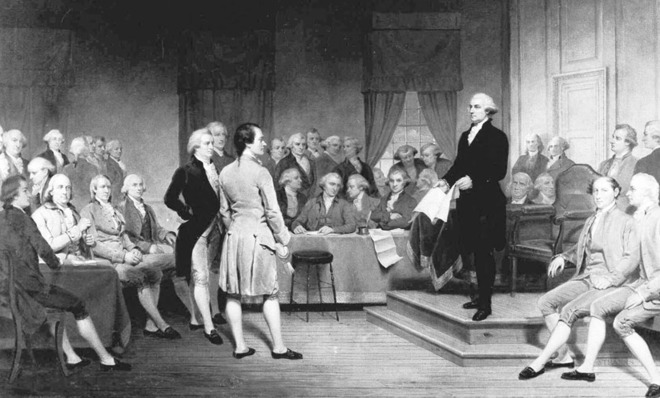

No wonder, then, that some of us seem to be taken with the idea of solving our political problems by calling a constitutional convention to craft a new founding document — one that is less… well, it sort of depends on what you find intolerable about the present system.

Conservatives spend their days dreaming of a balanced budget amendment, term limits for Supreme Court justices, and special protections for the free enterprise system.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Libertarians worry about ever-expanding executive power.

Liberals agonize over the influence of wealthy special interests on all branches of government.

Centrists fret about generalized governmental dysfunction and the danger that it will lead to the kind of breakdown that we've seen in presidential democracies throughout the developing world.

I have sympathy for a number of these complaints, especially the ones highlighted by the liberals and centrists. But that doesn't mean calling a constitutional convention is a good idea. On the contrary, it's an atrocious idea — and one that would be likely to make our very real problems far worse.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This isn't just an academic exercise. Last April, Michigan became (by some counts) the 34th state to endorse a constitutional convention. That's two-thirds of the states, meaning that under Article V of the Constitution, such a convention could arguably be called at any time.

Now it's true that most of these states have voted to convene a convention not because they want to scrap the Constitution and start over completely. Instead, they're proposing to use a convention to draft and approve various amendments to the current constitution. The Constitution stipulates two methods of amendment. The first is the method that's been used for all 27 amendments so far, which involves a two-thirds vote in both the House and Senate before the resolution is sent to the states for ratification. The other, which has never been used, requires that a convention be convened.

So why not hold a convention?

For one thing, because many jurists and constitutional scholars contend that once such a convention is convened, its agenda and scope cannot be controlled. For the first time since 1787, the fundamental law of the United States would be up for debate from top to bottom.

But with our political system suffering from so many maladies, why should that worry us? Perhaps we should take advantage of the opportunity to restructure the Constitution in a more essential way. Maybe we'd be better off with a parliamentary system of government, including more proportional representation. Maybe we should welcome an electoral system that promotes the growth and proliferation of parties, encourages them to form coalitions, removes some of the veto points that increasingly paralyze our politics, and ties executive power more closely to the legislative branch of government.

If it truly were possible to start over from scratch, with some extra-political lawgiver poised to bequeath a new Constitution more suitable to modern America, then maybe this would be an appealing prospect. But of course that isn't possible. There is no such savior waiting beyond the political fray to ride to our rescue.

And that means that any constitutional convention would reflect the same fractiousness and embody the same pathologies that already plague our political culture. Conservatives would favor some provisions, liberals would prefer others, and centrists would back still others. Special interests and the wealthy, meanwhile, would spare no expense trying to influence the proceedings, with the stakes exponentially higher than they are with any specific piece of legislation.

If petty corruption, influence peddling, and bureaucratic incompetence increasingly infest Washington, can you imagine what we'd see surrounding deliberations over how to rewrite the rules of the game from scratch?

I find the thought pretty chilling, and so should you.

However frustrating, inefficient, and inept government seems today, rest assured that it could be worse. Much worse.

When it comes to the Constitution, change just isn't something we can believe in.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred