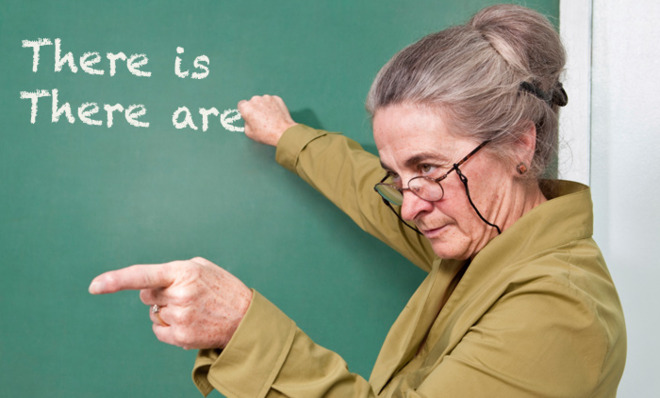

There's a number of reasons the grammar of this headline could infuriate you

Blame our shifting definitions of the singular and the plural

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There's a number of reasons this sentence could be right. But do you think it is?

It's not uncommon; the set of words "there's a number of reasons" gets almost 3 million hits on Google. But the phrase "there are a number of reasons" returns more than 63 million results. And perhaps the least natural-sounding possibility, "there is a number of reasons," gets even more hits: About 73 million.

So there's a division of opinions. But this division is a strange one. The people who prefer "there's a number of reasons" are likely to be either very sloppy or very fussy, while the great middle ground is occupied by those who prefer "there are a number of reasons." The reason for this is that there are two different things at issue, and they are at cross-purposes.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The two issues are: (1) Is it acceptable to use there's when the noun following it is plural? and (2) Is a number of reasons singular or plural?

The first issue is the simpler one. English has a long history of using there as a filler word that allows us to declare the existence of something while putting the thing itself in the more emphasized position after the verb. Several verbs (such as seem) can work this way, too. Since there is not a noun or pronoun, the verb in the sentence as a general rule agrees with the noun following it. An egg is on the table; there is an egg on the table. Two eggs seem to be on the table; there seem to be two eggs on the table. There are two eggs on the table.

This comes up against the fact that there's is commonly treated in casual and dialectal speech as a fixed, unchanging item. Many well-educated people who wouldn't write, "There's two eggs on the table" would nonetheless say it without thinking. That doesn't make it correct in formal English, however — and if it ever does come to be seen as correct, it will likely be a long time in the future.

The more interesting — and more hotly debated — question is whether a number of reasons is singular or plural.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Those in the "singular" camp are another split group: Some of them are linguistically insecure and second-guess themselves, and some of them are extremely confident and assertive in matters of grammar. They point out that a number is the head of the noun phrase and is singular.

Those in the "plural" camp can point out that a lot, a bunch, a couple, a dozen, a hundred, a thousand, and a million are all singular in form, too. Terms such as a dozen, a pair, and a couple started out as singular nouns, and you can still treat them that way if you're treating the dozen, pair, or couple as a unitary set. The indefinite plural quantifiers such as a lot and a bunch also have singular uses — "a bunch of people is coming" presents a different image than "a bunch of people are coming" — but they have gained a plural status even as they keep their noun role (we say "a bunch of people" and "a lot of people" and even "a great deal of people" but we don't say "a dozen of people" anymore).

The question, then, is whether a number falls into the same set as a lot and a bunch. When we say "a bunch of flowers is on the table" we are referring to the bunch as whole; if we say "a number of people is coming," do we expect to see a number — say, 23 — walking in the door?

The same question holds for a few other similar terms, including a large percentage and the majority. Have they shifted or extended to have a quantifier usage? If we look at historical usage data, we will find that "a large number are," "a large percentage are," and "the majority are" all beat out their "is" counterparts, sometimes by large margins, at least since 1800. Could all those users be wrong? Or is it perhaps more likely that those in the "singular, you idiot!!!" camp are misanalyzing the grammar?

Here's one way to test it: Use other verbs instead of is/are. Take this sentence: "Among students, a large percentage graduates from high school, the majority finishes college, and a fair number goes on to graduate school." Does it sound more natural with graduate, finish, and go on? Try this: "We have many guests, and a number of them uses the shower every day." Better with use?

Here's another way to test it: Look for distinctions in meaning. We know we can say, "The majority is always right," meaning that, as a body, those constituting the majority prevail. What if we say, "The majority are always right?" Then it more readily means that of this population, the set of those who are always right is greater than the set of those who are not. So we do have a distinctive plural usage of the majority.

Similarly, "A high percentage get an A on the test" means very many of them get an A. On the other hand, "A high percentage gets an A on the test" means that a high percentage (say, 90 percent) on the test will get you an A.

And if we say, "Many people showed up for our sign-making party, and a large number is sitting on the lawn," we mean that there is an enormous numeral figure on the lawn, perhaps painted by those present. If we say, "… and a large number are sitting on the lawn," we mean a lot of people are. A big bunch. A great deal. Many.

Of course, if everyone were to take the time to look at standard authoritative references on grammar — Oxford, Fowler's, usage dictionaries, etc. — no one would say a number of has to be singular. But people who think the answer is obvious don't always see the need to double-check.

In short, if I say, "There is a number of reasons written on the paper," expect to see a figure such as 5, 12, or 67. If I say, "There are a number of reasons written on the paper," expect to see the reasons themselves. And if I say, "There's a number of reasons written on the paper," well, it really depends on just how casual I'm being with my speech — but don't expect me to use it in earnest in formal written English. There are a number of reasons I wouldn't.

James Harbeck is a professional word taster and sentence sommelier (an editor trained in linguistics). He is the author of the blog Sesquiotica and the book Songs of Love and Grammar.