Is bipartisan foreign policy making a comeback?

Since Russia's invasion of Crimea, Democrats and Republicans have basically been getting along

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The partisan sniping surrounding Russia's annexation of Crimea is still hot. Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) recently said the White House response to Russia's actions has been "timid." Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) implied that Republicans deserve the blame, saying events may have "unfolded differently" if Republicans hadn't held up his Ukraine aid bill.

And yet, aid to Ukraine won a big bipartisan vote this week. Reid jettisoned a provision reforming the International Monetary Fund resisted by Republicans, and in return, Republicans are buttressing President Obama's approach to Russia instead of undermining it.

Might this be a return to the mythic days of old when partisan politics stopped "at the water's edge"?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Despite all the political flak in the air, the two parties are being brought closer together over Russia. A common animus toward Russian President Vladimir Putin has emerged, with many Republicans skeptical of Russia's interest in diplomacy and many Democrats seething at Putin for whipping up homophobia in his country.

But there are other factors, beyond an easy dislike of the Russian strongman, that help diminish the partisan daylight.

One is the widespread war-weariness after the messy outcomes of Iraq and Afghanistan, which is hemming in the militaristic impulses of the Right. As Paul Waldman, writing in the Washington Post, recently observed, the neoconservative "tough guys" aren't being so tough anymore: "These days it's all imposing sanctions and freezing assets and boycotting economic summits and making statements."

Case in point: McCain, in a speech earlier this month scorching Obama for being "M.I.A.", was forced to concede that in Ukraine "there is not a military option that can be exercised now." McCain and other Republicans had been pressing Obama to levy economic sanctions, expel Russia from the Group of Eight, and — in what amounts to the closest call for actual military action — send military aid to the Ukrainian government. Obama did the first two and has left the door open to the third. Furthermore, the Senate's No. 2 Democrat, Richard Durbin (Ill.), not considered to be hawkish, backs military aid.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The second factor is a shared bipartisan unease with the public's turn toward isolationism, and the potential for Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) to capitalize on it in the 2016 presidential campaign. The percentage of the public that believes America should "take the leading role among all other countries in the world in trying to solve international conflicts" is down 17 points since 2003, hitting 31 percent in a February CBS/New York Times poll.

McCain vented his concern with Paul's rising influence last year when he said, "There are times these days when I feel that I have more in common on foreign policy with President Obama than I do with some in my own party." These remarks are proving more relevant than his broadsides against Obama. It was McCain who led the Republican charge in the Senate for Ukraine aid, while Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) shed his long-standing internationalism in order to fight for his political life in the state that Paul also represents.

If these seem like thin reeds on which to claim the return to a bipartisan foreign policy, keep in mind that partisanship beyond the water's edge has long been standard operating procedure, not the other way around.

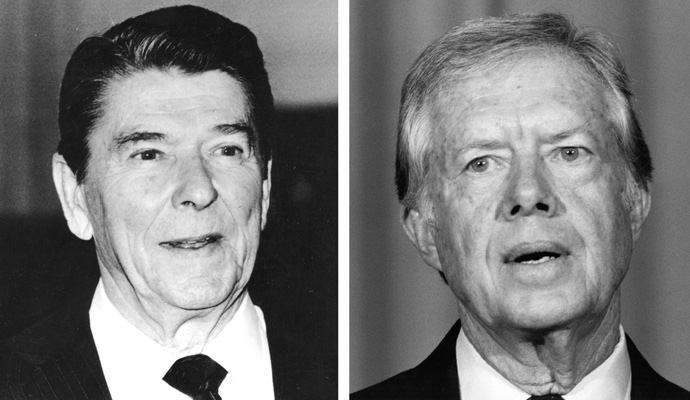

Senate Republicans thwarted President Woodrow Wilson's dream for a League of Nations. Dwight D. Eisenhower won the presidency by slamming Harry Truman's handling of the Korean War. Adlai Stevenson later accused Eisenhower of losing the Cold War. Richard Nixon challenged Lyndon Johnson's management of the Vietnam War, and four years later George McGovern was doing the same to Nixon. Republicans savaged President Jimmy Carter for ceding control of the Panama Canal to Panama and for the Iran hostage crisis. Democrats were panicked that Ronald Reagan was going to get us into a nuclear war with the Soviets, and the Reagan administration was hobbled by the Iran-Contra affair. House Republicans refused to back President Bill Clinton's bombing campaign to stop ethnic cleansing in Kosovo. And of course, Democrats pounded George W. Bush over Iraq.

Just to name a few.

So a degree of public friction is always to be expected. In many of the above cases, disputes were based on deep philosophical differences regarding the value of confrontation and negotiation. Those differences remain today as Republicans scoff at Obama's negotiations with Iran and the Palestinian Authority.

But there might be something new at work regarding Russia. Republicans are shying away from crude militarism, while President Obama is turning toward confrontation, and the ideological gap has narrowed. If that proves to be an anomaly that only applies to Russia, little has really changed. But if this common ground leads to a broader understanding of foreign policy objectives and tactics between the parties, that could bolster a true bipartisan consensus as Obama finishes the final leg of his presidency.

Bill Scher is the executive editor of LiberalOasis.com and the online campaign manager at Campaign for America's Future. He is the author of Wait! Don't Move To Canada!: A Stay-and-Fight Strategy to Win Back America, a regular contributor to Bloggingheads.tv and host of the LiberalOasis Radio Show weekly podcast.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred