How to read your shampoo bottle

Don't be stumped by the ingredients in your beauty products

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Stop what you're doing right now and take a shower. Use your fanciest natural herbal shampoo, your fanciest natural herbal conditioner, and your fanciest natural liquid soap. Then use your expensive moisturizer. And while you're doing all that, look at the ingredients they list on their labels. Go ahead, I'll wait.

You back? So how about those ingredients? Do they seem a little…esoteric?

OK, well, let's just say that such products almost always list their first ingredient as aqua.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Sometimes they helpfully translate that from the Latin: "water."

And one of the last ingredients listed is usually parfum. Which is French for "fragrance."

They can't just give you the ingredients in straightforward English. You're paying too much for that. The ingredients have to scream clinical and botanical. Natural and healthy. And beautiful, of course. So for the botanical, they use the Latin names. For the clinical, they sometimes also use Latin, but sometimes deploy weird English names based on Latin and Greek roots. And for the beauty? There's always that whiff of Paris.

Here's a quick guide to the ingredients — and what they mean — in those beauty products you paid 30 bucks for.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The plants

Rosmarinus officinalis is, as you may guess, rosemary. Everyone has some in their kitchen for stews and sauces and so on. What's officinalis? Carl Linnaeus, the guy who invented the Latin biological naming system, used it to mean the plant had an established medical and/or culinary use. It's from Latin officina, or "workshop," which came to refer to a storeroom, and later on to a pharmacy. Similar ingredients include Calendula officinalis (marigold) and Salvia officinalis (sage).

Lavandula angustifolia is lavender, so you'll see it in a lot of bathroom products. What's angustifolia? It sounds so august — or maybe Scottish (Angus) — but it just means "narrow-leaved."

If there's sage and rosemary, why not thyme? Thyme is on the label as Thymus vulgaris. There's no way to make vulgaris not sound, um, vulgar. But it's just Latin for "common" — as in "garden variety." You'll see it in quite a few Latin names for plants.

Aloe barbadensis is aloe vera — as grown in Barbados, hence barbadensis. Actually there are several different Latin names for the same aloe plant, due to different botanists giving it different names. But barbadensis sounds warm and sunny, if you recognize the Barbados in it.

References to places show up in quite a few plant names. For example, there's Simmondsia chinensis, better known as jojoba; the chinensis means "Chinese," just as it looks, even though jojoba is from California and Mexico — the botanist who gave it the name misread the "Calif" on the label as "China." There's also Camellia sinensis; the sinensis also means "Chinese" — that's the more classically Latin way to say it. Oh, what is Camellia sinensis? Tea. As in what you drink from a cup.

You can probably guess what Citrus medica limonum is. Yes, it's lemon. What's up with the medica? It comes from citrons having been thought to originate in the land of the Medes (Persia). It has no reference to medicine at all. But boy, it sure sounds clean and clinical, doesn't it?

If you buy anything with shea butter in it, you're likely to see Butyrospermum parkii in the ingredients. That's the old Latin name for the shea tree. It means "Park's butter seed" — Park being Mungo Park, the Scottish explorer who found out about the tree from the Africans who had known about it since forever. Funny how they're not mentioned (though shea is actually a British-influenced rendition of shi, the Bembara name for the tree). The more correct current Latin name is Vitellaria paradoxa, but that doesn't sound as good for your skin.

Chamomilla recutita is the plant that is officially called Matricaria chamomilla or Matricaria recutita. Chamomilla recutita is a version you may see on a label, but is not technically right. It's chamomile, as you probably suspected. The Matricaria comes from matrix (which is related to mater, "mother") and recutita means "skinned."

Helianthus annuus is sunflower. Helianthus is a Latin version of the Greek for "sunflower." Annuus means it lasts a year. Note the double n and double u — in fact if you rotate annuus 180 degrees it almost looks the same, for no particularly good reason.

The acids and alcohols

You'd think you wouldn't want to be putting a lot of acids on your face and hands. But actually not all acids are all that, well, acidic — not as we think of it. Shea butter, for instance, is made up of fatty acids. They're technically acids because of their chemical composition, but when you rub them on your skin, they sure don't corrode it. So when you see palmitic acid, stearic acid, lauric acid, linoleic acid, arachidic acid, oleic acid, capric acid, caprylic acid, or myristic acid on the label, don't worry. It just means you're using shea butter, cocoa butter, palm oil or something like that.

Likewise, you may think alcohol would be hard on your skin. But not all alcohols are the same. There are such things as fatty alcohols — and I don't mean Irish cream. Any organic chemical that has a hydrogen-and-oxygen pair attached to a carbon atom is technically an alcohol. So cetyl alcohol, stearyl alchol, and cetearyl alcohol are not things to worry about — or drink.

The other strange crap

Does propylene glycol look familiar? Someone may point out to you that it can be used as antifreeze. That's true, but so can alcohol, of the kind you can drink. Plenty of things that are perfectly safe to eat and put on your face are used for scary-sounding applications, such as cleaning and de-icing. In personal care products, propylene glycol is mainly used to preserve them and keep them moist.

Tocopherol and panthenol are another two –ol things. Actually, they're vitamins — vitamin E and vitamin B5, respectively.

Cocamidopropyl betaine may look scary, but it's just there as a surfactant — it reduces liquid surface tension, allowing the product to spread and wet things better. The coca means that it's derived from coconut oil (not the coca plant). Another surfactant you'll see is lecithin.

Hydrolyzed wheat protein is used to help things stick together. It's one of a few things you may see that are hydrolyzed, which means they use water to break down some chemical bonds.

And then there are some really fun long chemical names. Hydrolyzed wheat protein is also called stearyldimoniumhydroxypropyl, for instance. And there's an antibacterial and antifungal ingredient called methylchloroisothiazolinone. These words, like the molecules they name, are made up of smaller pieces stuck together, and if you take some time to get to know these, you'll begin to recognize the bits.

For instance, in methylchloroisothiazolinone, thiazol(e) is a molecule made with a ring of three carbons, one nitrogen, and one sulfur; in(e) means it's actually a molecule like thiazole but just slightly different; methyl means it has a carbon atom attached to four hydrogen atoms as part of it; chloro means it has a chlorine atom attached to it; iso is from Latin for "same," which means that the molecule has the same parts as another one but in different arrangement; and one means it has an oxygen atom attached to it.

So now you don't need to bring a book to read in the bath, where you could risk dropping it into the water and ruining it. You can spend a happy 10 minutes or more reading the ingredients on your beauty stuff instead.

James Harbeck is a professional word taster and sentence sommelier (an editor trained in linguistics). He is the author of the blog Sesquiotica and the book Songs of Love and Grammar.

-

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek star

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek starIn The Spotlight Van Der Beek fronted one of the most successful teen dramas of the 90s – but his Dawson fame proved a double-edged sword

-

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?Today's Big Question The King has distanced the Royal Family from his disgraced brother but a ‘fit of revolutionary disgust’ could still wipe them out

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

10 signature foods with borrowed names

10 signature foods with borrowed namesThe Explainer Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

-

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged cultureThe Explainer We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

-

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous authorThe Explainer The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

-

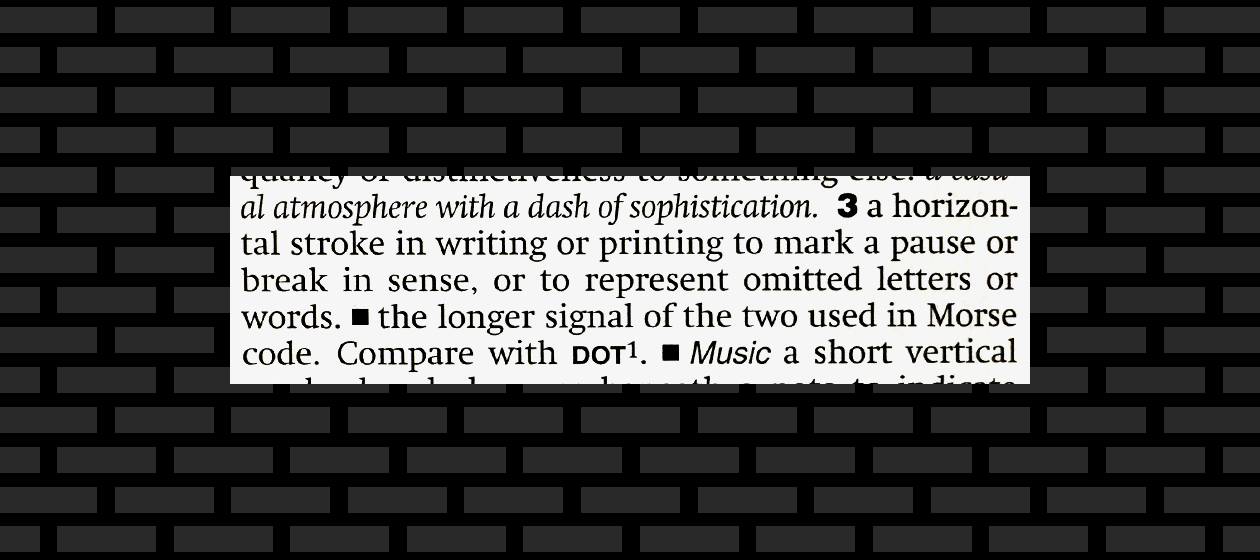

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guideThe Explainer Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.