The religious right is finished. So what's next for social conservatives?

As its political influence wanes, a once-powerful movement finds itself at a crossroads

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Remember the religious right?

No, I'm not talking about patently ridiculous efforts to mobilize the Republican base for the upcoming midterm elections by reframing abortion as a tax-and-spend issue.

I mean, rather, the political movement that united conservative evangelical Protestants, Catholics, Mormons, Jews, and Muslims around an ideology derived from the encyclicals of Pope John Paul II. This ideology sought to institute a "culture of life" that would outlaw abortion, gay marriage, euthanasia, and maybe even contraception and all non-procreative sex acts (masturbation, oral sex, anal sex) — with all of this rooted in a distinctive interpretation of the nation's founding documents that wedded them with medieval concepts of natural law.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

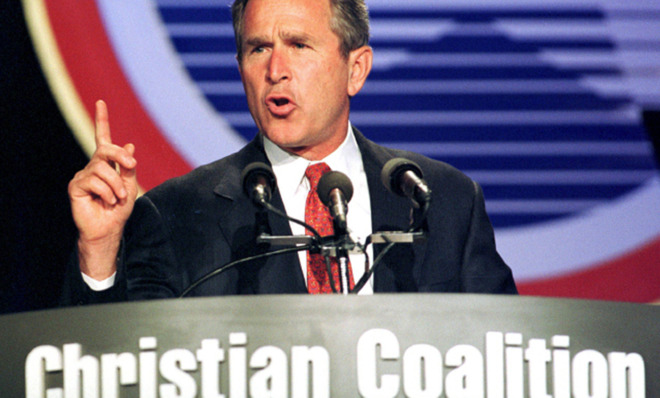

This religious right — which helped deliver a solid re-election to George W. Bush in 2004, and reached its peak of influence just after that election with the federal intervention in the sensational right-to-die case of Terri Schiavo — is finished.

Its decline since 2005 can be traced to numerous causes: The right's widespread disappointment with the legacy of the Bush years across a range of areas, including fiscal, foreign, and social policy; the shift of the national GOP toward economic libertarianism in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008, the election of Barack Obama, the rise of the Tea Party, and the passage of health care reform; and finally, a dramatic and rapid shift in the culture, especially among the young, away from politicized religion and toward the acceptance of gay marriage.

In the wake of these changes, the remnants of the religious right have been reduced to playing defense. No longer portraying themselves as the nation's "Moral Majority," they're now focused on the much more modest task of protecting themselves from state-mandated secularism. Where they once tried to ban gay marriage in the Constitution, now they fight to ensure that the government will allow conservatives to pass on their anti-homosexual beliefs in their own homes, churches, and schools. Where they once dreamed of outlawing contraception, now they fight to keep the government from forcing Catholic institutions to pay for insurance that provides it.

But this defensiveness doesn't mean the populist energies behind the religious right have disappeared. On the contrary, millions of Americans continue to consider themselves religious conservatives. What will come next for these voters, now that the original religious right is fading out?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There are at least four possibilities.

The first and most likely development is one that's already underway: A stepping back from national ambitions across a range of issues to a narrower emphasis on state-level initiatives that restrict access to abortion. This is a shrewd move, politically speaking. Thanks to advances in ultrasound technology, public opinion on abortion is likely to remain deeply conflicted, with strong support for reproductive freedom coupled with a strong moral aversion to both late-term abortions and the termination of pregnancies for what many judge to be frivolous reasons.

The focus on passing legislation in conservative-leaning states, meanwhile, allows the remnants of the religious right to maximize the impact of their limited resources. The end result, at least in the short-to-medium term, is likely to be greater ideological polarization across the country, with abortion harder than ever to procure in some states and others proudly trumpeting their absolute commitment to reproductive freedom.

Those who are working to throw up barriers to abortion are foot soldiers in the pro-life movement, many of them driven to political activism by their religious faith. But many younger religious conservatives approach political engagement differently. In comparison with their parents, they tend to be more liberal on homosexuality, more critical of capitalism, and more concerned about the environment.

This could lead the younger generation of religious conservatives — in a second possibility — to form a new national political movement around a broader cluster of concerns that goes beyond the confines of the culture war, perhaps tied to issues of economic stewardship and environmental sustainability. The question then would be whether this new movement would continue to work through the GOP, be tempted by the Democrats, or entertain the prospect of forming a new political party.

Or maybe, in a third possible development, the next generation of religious conservatives will take a different path, withdrawing from politics altogether, as the original Protestant fundamentalists did from the 1920s through the 1960s. There is already some evidence that younger religious conservatives are more inclined than their parents to look with suspicion on politicized faith. If this inclination persists, perhaps further encouraged by increasing disappointment with the available political alternatives in the United States, it could drive religiously devout conservatives away from activist engagement entirely.

Which brings us to a fourth and final option for religious conservatives disenchanted by both the American political system and the increasingly secular drift of American culture. Instead of giving up and going home, they could turn outward (even more than they already have) — focusing on Africa, Latin America, Asia, and the Middle East — places where they may find a more receptive audience for their critique of cultural decadence. Call it the globalization of the culture war.

Indeed, in the coming years, all four options may play out in varying degrees, as well as others, splintering the religious right even further. What remains to be seen is whether any of those factions will exercise anywhere near the level of influence the religious right once enjoyed — or if, instead, the decline will continue, genuinely marking the end of a recent chapter in American political history.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.