5 reasons why gun control failed

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Why did a relatively modest, very popular gun control bill fail? A lack of big-think words like "will" and "imagination"? Too little or too much intervention from the White House? Naw. Here are five of the many reasons:

1. An interest group imbalance

The gun control lobby might have resources now that it didn't have in the past, but its relationship with most lawmakers is nothing like the NRA's. It has not only kept sustained pressure on Democrats and Republicans, but has also actively cultivated relationships with key constituencies in their districts. The NRA is able to generate a lot of smoke without much fire. And politicians will instinctively react to the political pressure that is available to them at moments in time.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

2. The disconnect between the tragedy and the proposed solutions

Background checks for the mentally ill, a ban on certain types of semi-automatic weapons, and even magazine clip restrictions would not have prevented the tragedies. Undoubtedly, they might have helped prevent future tragedies, and probably would have provided momentum for tougher state measures. But the nexus of the factors — mental illness, gun culture, personal history — is too complex for solution. Lawmakers can get away with thinking that a "yes" vote would have not retrospectively helped to reduce pain and suffering. It's weird thinking, but it works.

3. The lies and distortions of the NRA

Washington still hesitates to use the "L" word, and even though the media generally favors gun control, it hesitates to call out the NRA for its lies. Further, whenever the media calls out a generally conservative cause on something, the issue polarizes, even if vast majorities of the American people putatively support the underlying policy that is being lied about.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

4. The myth of the "Bargaining Chip" strategy.

Or, rather, its failure in this instance. Megan McArdle explains it best:

There's only so much that you can get out of a negotiation, and no matter where you start out, you aren't going to move beyond that. Academics who study this call it the Zone of Possible Agreement. In a traditional sales negotiation, it is defined by the highest possible price that the buyer is willing to offer, and the lowest possible price that the seller is willing to accept.

Say we're haggling over a new car. The car cost the dealer $14,000, and the fixed costs of the lot and so forth mean that he needs to make another $1,000 on the car to break even. His "reservation price" is $15,000. You are willing to pay as much as $18,000 but would of course prefer to get it for less. Which means that to make a deal, you are going to settle on a price somewhere between $15,000 and $18,000.

The dealer will probably price the car high — say, $20,000 — in order to get more money out of you. You will probably give him a lowball offer in order to pay less. But no offer that you make is going to allow you to pay $13,000 for the car; no price he sets will yield him a final sales price of $19,000. Those prices are outside the ZOPA, which means that one party will walk away rather than make a deal.

Can you move the boundaries of the ZOPA? Yes. In fact, Newtown did just that for gun controllers. But what professional negotiators understand, and gun rights activists apparently don't, is that your starting position is not what changes the ZOPA. Oh, there are rare instances where you happily discover that the other side wants something very much that you don't care about at all. But the stuff that actually shifts the ZOPA usually happens outside the negotiation: shifts in the legal climate, or public opinion, or some other factor.

In fact, by demanding too much, you can often worsen the chances for a deal. That's why negotiators typically start off with a price that's outside the ZOPA, but not so far outside that you shut down negotiations. [Daily Beast]

5. The structure of the American Republic

Rural parts of rural states, and rural states, have significantly disproportionate power when numbers matter. And given the polarization typically associated with gun control, it split right along the big populous urban metropolis / small rural town border. The sad truth is that Americans who oppose gun restrictions oppose it more fiercely than Americans who support gun restrictions. That energy matters, and is multiplied by the distorted political franchise given to less populous states.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

How to navigate dating apps to find ‘the one’

How to navigate dating apps to find ‘the one’The Week Recommends Put an end to endless swiping and make real romantic connections

-

Elon Musk’s pivot from Mars to the moon

Elon Musk’s pivot from Mars to the moonIn the Spotlight SpaceX shifts focus with IPO approaching

-

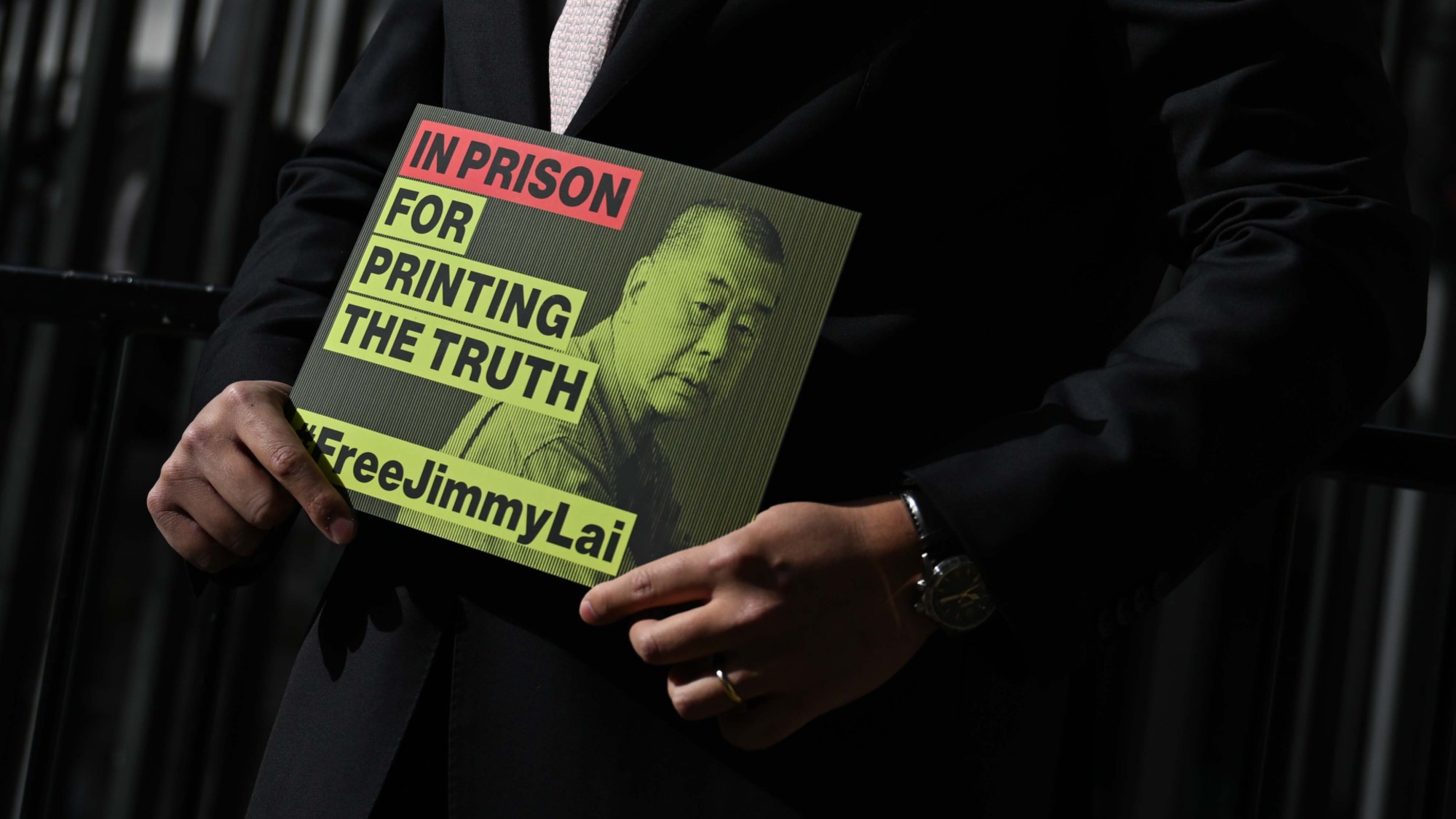

‘Hong Kong is stable because it has been muzzled’

‘Hong Kong is stable because it has been muzzled’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred