9 compellingly strange letters you don't know about

Meet eng, thorn, hwair, and more

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

1. ŋ

What it's called: Eng.

Who uses it: Many African languages (e.g., Bambara, Bemba, Dinka, Ewe, Ewondo, Fula, Ganda, Maasai, Nuer, Shilluk, Tuareg, Wolof), several North American languages (e.g., Nuu-Chah-Nulth, O'odham), and a few others.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What it stands for: The "ng" sound as in "sing."

Where it comes from: The letters n and g merged; it was designed by a typographer in 1619.

In English: We should have started using it as soon as it was invented, because we need the darn thiŋ. But it only shows up in pronunciation guides.

2. ɔ

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What it's called: Open o.

Who uses it: Mainly African languages from several linguistic families; e.g., Aja, Akan, Bambara, Dinka, Ewe, Ewondo, Nuer, Shilluk, Twi.

What it stands for: The vowel sound you hear before the "r" in "or"; or, in some accents of English, in words such as "caught."

Where it comes from: The International Phonetic Alphabet. It was made by turning the letter c 180 degrees.

In English: The English alphabet has never had a place fɔr it, except in some pronunciation guides.

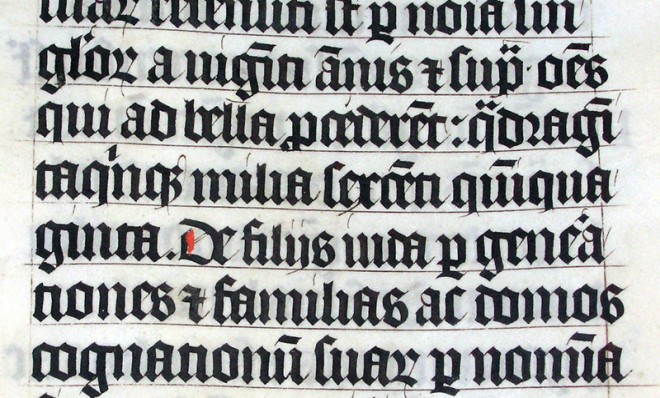

3. þ

What it's called: Thorn.

Who uses it: Icelandic.

What it stands for: The consonant you hear at the beginning of "thin."

Where it comes from: The Elder Futhark runic alphabet. It was borrowed by Old English and Old Norse because the Latin alphabet didn't have a letter for the sound.

In English: This used to be an English letter. It and the letter eth (ð) stood for the sounds at the starts of "thin" and "this," and were often used interchangeably. (Icelandic also uses ð, just for the consonant you hear at the beginning of "this.") Why did we stop using it? Because Europeans didn't use it, and European-trained scribes didn't like it. When we got moveable type, the letter sets didn't include it. For a while the letter y was used to stand in for it, as in ye for þe (yes, the word the — it was not pronounced "ye"), but finally th won out.

4. ƿ

What it's called: Wynn.

Who uses it: Old English did.

What it stands for: "W."

Where it comes from: Those runes again. Notice that this letter lacks the ascender you see on þ, and the bottom of the loop angles down like in a y rather then up as in a p.

In English: The letter w has only been its own letter for a few hundred years. Before that, languages that needed it often used uu or vv (which used to be the same letter — u was just a variant form of v, and both were used for the sounds we now write u and v), but Old English scribes decided it made more sense to borrow a proper distinct letter for it. But it fell out of use. In fact, today even in modern printings of Old English texts the letter w is used, because ƿ looks too much like p. Wynn? More like can't win!

5. ƕ

What it's called: Hwair.

Who uses it: Gothic did, but no one has spoken Gothic for about 1200 years.

What it stands for: "Hw."

Where it comes from: The letters h and v merged.

In English: Although we used to have hw (or hƿ) all over the place — respelled now as wh — we never used this letter. Don't know ƕy not!

6. ƣ

What it's called: Gha.

Who uses it: various Turkic languages used to; they've all replaced it with other letters now.

What it stands for: Usually a voiced velar fricative — which is like the "ch" in German "ach" but voiced.

Where it comes from: A modified version of a handwritten q.

In English: We've never even thought about using this letter. English did used to have the sound it stands for, but it used a different letter for it.

7. ȝ

What it's called: Yogh.

Who uses it: No one now, but English and Scots used to.

What it stands for: A voiced velar fricative (see above) or the "y" sound, usually.

Where it comes from: A handwritten form of g.

In English: At first, English didn't need this letter; then it did, so it used it. Then it replaced the letter with gh because of those darn Europeans (see þ, above). Then it stopped using the sound. Meanwhile, Scots, also under the influence of European letter sets, replaced the letter with z, giving rise to names like Dalziel (pronounced like "deal"), Menzies (pronounced like "mingis"), and Kenzie (which used to be pronounced like "ken ye").

8. ʒ

What it's called: Ezh.

Who uses it: Some kinds of Sami, which is spoken in Norway and a bit of Russia; also, some African languages.

What it stands for: In the International Phonetic Alphabet, this stands for the "zh" sound you hear in "pleasure" and "Zhivago," but Sami uses it for a "dz" or "j" sound.

Where it comes from: A handwritten form of the letter z.

In English: We've had the sound in our language ever since we borrowed it from French, but we treaʒure our leiʒure too much to exert the effort to use a new letter for it.

9. ʔ

What it's called: Glottal stop.

Who uses it: Mostly North American languages (e.g., Klallam, Nuu-Chah-Nulth, Chipewyan).

What it stands for: The sound between the vowels in "oh-oh" and "uh-uh," and the sound we usually make in place of the "t" in "button" — and that Cockneys (among others) regularly replace "t" with in many places.

Where it comes from: A development of the form of an apostrophe to look pretty much like a question mark without a dot; it's the symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet for this sound.

In English: Where we need to represent this sound explicitly, we usually just use an apostrophe. So do many languages. But apostrophes are used for so many other things… Do I think we'll ever start using this in normal written English, though? Nuʔ-uh.

James Harbeck is a professional word taster and sentence sommelier (an editor trained in linguistics). He is the author of the blog Sesquiotica and the book Songs of Love and Grammar.

-

Political cartoons for February 12

Political cartoons for February 12Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include a Pam Bondi performance, Ghislaine Maxwell on tour, and ICE detention facilities

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’

-

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ film

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ filmThe Week Recommends Akinola Davies Jr’s touching and ‘tender’ tale of two brothers in 1990s Nigeria

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

10 signature foods with borrowed names

10 signature foods with borrowed namesThe Explainer Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

-

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged cultureThe Explainer We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

-

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous authorThe Explainer The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

-

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guideThe Explainer Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.