Wardell Quezergue, 1930–2011

The ‘Creole Beethoven’ of New Orleans

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Wardell Quezergue was a young Army private stationed in Japan in 1951 when his unit got the order to head to the Korean front. En route to the airport, Quezergue was abruptly sent back to base to arrange music for a military band; the soldier who replaced him was killed in combat. Fifty years later, Quezergue, by then a legendary arranger who had produced some of New Orleans’s most enduring R&B hits, released A Creole Mass, an orchestral tribute to his stand-in and the other men who died in that war.

Born in New Orleans to a musical family, Quezergue (pronounced ka-ZAIR) had his first professional gig playing the trumpet at age 12, said the New Orleans Times-Picayune. After his Army service, he returned home and became a popular bandleader and musician. But he “discovered he also had a talent for producing and arranging other musicians’ music,” and went on to work with artists such as Fats Domino, the Neville Brothers, B.B. King, Dr. John, Paul Simon, and Stevie Wonder.

Nicknamed the Creole Beethoven, Quezergue left his imprint on scores of New Orleans hits, including “Iko Iko” for the Dixie Cups, “Big Chief” for Professor Longhair, “Mr. Big Stuff” for Jean Knight, and “Groove Me” for King Floyd, said the Associated Press. He co-wrote the brass-band standard “It Ain’t My Fault,” later sampled by Mariah Carey and others, and co-founded Nola Records, where he produced Robert Parker’s Top 10 hit “Barefootin’.” “He was a superb musician and bandleader,” said musician Allen Toussaint. “He always inspired the best out of people who were playing with him.”

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Quezergue lost his eyesight to diabetes in 2003, and later lost “a lifetime collection of sheet music” when his home was destroyed by Hurricane Katrina, said The Wall Street Journal. He eventually returned to New Orleans, and in 2009, some of the Big Easy’s top musicians headlined a tribute to him at New York’s Lincoln Center, a rare honor for an arranger. Quezergue was a master of all styles, Toussaint said. “Just drop him off on Planet Music and he was fine.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Catherine O'Hara: The madcap actress who sparkled on ‘SCTV’ and ‘Schitt’s Creek’

Catherine O'Hara: The madcap actress who sparkled on ‘SCTV’ and ‘Schitt’s Creek’Feature O'Hara cracked up audiences for more than 50 years

-

Bob Weir: The Grateful Dead guitarist who kept the hippie flame

Bob Weir: The Grateful Dead guitarist who kept the hippie flameFeature The fan favorite died at 78

-

Brigitte Bardot: the bombshell who embodied the new France

Brigitte Bardot: the bombshell who embodied the new FranceFeature The actress retired from cinema at 39, and later become known for animal rights activism and anti-Muslim bigotry

-

Frank Gehry: the architect who made buildings flow like water

Frank Gehry: the architect who made buildings flow like waterFeature The revered building master died at the age of 96

-

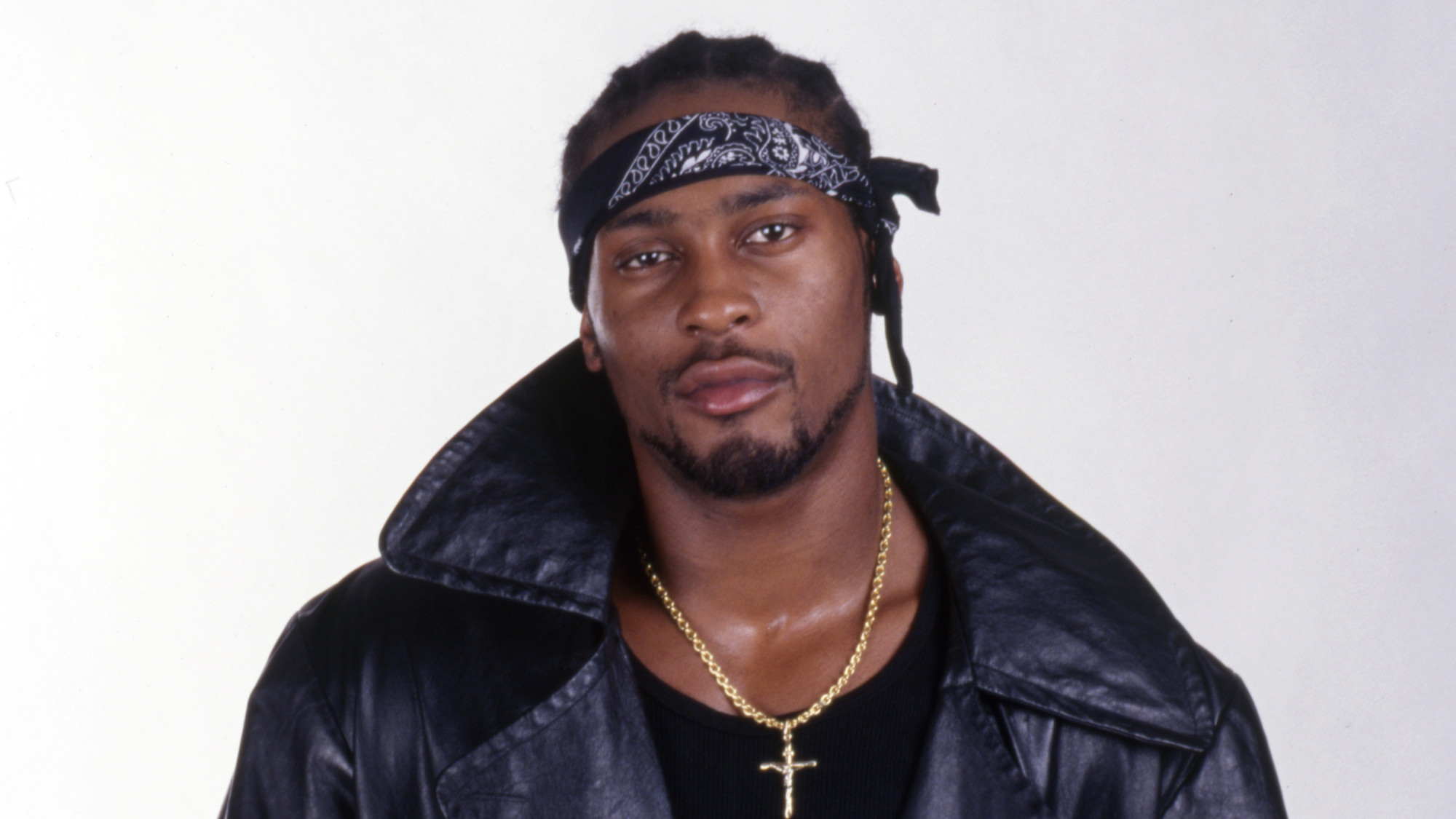

R&B singer D’Angelo

R&B singer D’AngeloFeature A reclusive visionary who transformed the genre

-

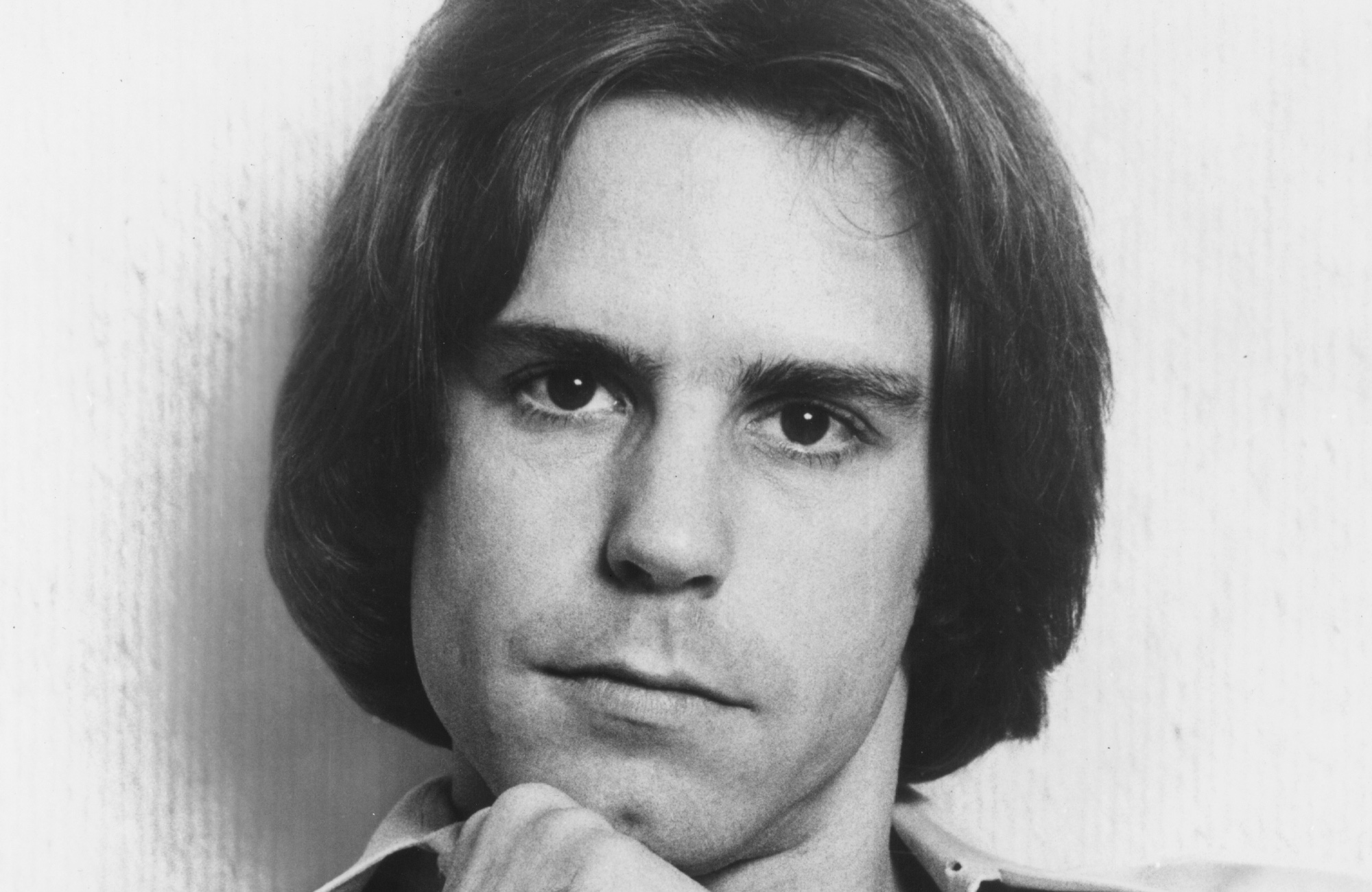

Kiss guitarist Ace Frehley

Kiss guitarist Ace FrehleyFeature The rocker who shot fireworks from his guitar

-

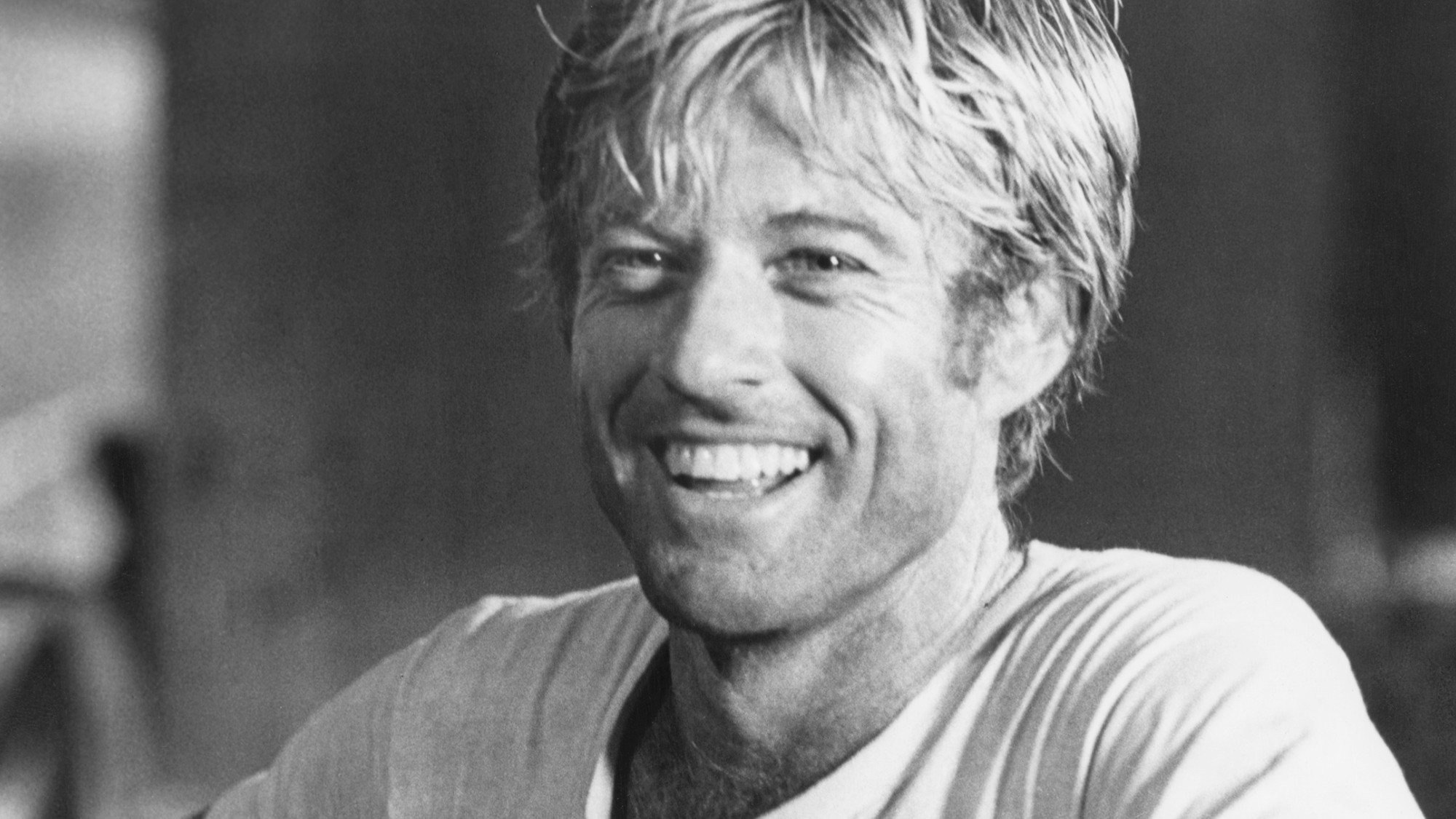

Robert Redford: the Hollywood icon who founded the Sundance Film Festival

Robert Redford: the Hollywood icon who founded the Sundance Film FestivalFeature Redford’s most lasting influence may have been as the man who ‘invigorated American independent cinema’ through Sundance

-

Patrick Hemingway: The Hemingway son who tended to his father’s legacy

Patrick Hemingway: The Hemingway son who tended to his father’s legacyFeature He was comfortable in the shadow of his famous father, Ernest Hemingway