Russia: Still waiting for democracy

Even for Russia, said Anne Applebaum in Slate.com,

Even for Russia, said Anne Applebaum in Slate.com, “this was a farcical election.” On Sunday, Dmitri Medvedev, 42, became the country’s president-elect, certifying an outcome that was preordained last December. That was when outgoing President Vladimir Putin personally anointed Medvedev, his Kremlin crony, as his successor. You have to wonder why anyone bothered voting at all. The only viable opponent, the liberal former Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov, was disqualified. Instead, Medvedev was pitted against three carefully picked straw men: “a clapped-out ‘Communist,’ a complete nonentity, and the ludicrous anti-Semite Vladimir Zhirinovsky.” Medvedev held no press conferences, didn’t debate his rivals, and spent only a single day campaigning. Yet he captured 70 percent of the vote. “The Kremlin did not just fix the elections,” said The Economist. “It made a mockery out of the process.”

So much for dreams of a free Russia, said The Boston Globe in an editorial. In his eight years in office, Putin has transformed a fledgling democracy into an authoritarian state that “braids together political, corporate, and secret-police powers.” He is not about to relinquish his grip. When Medvedev, as promised, names Putin prime minister this spring, he’ll likely continue to wield covert power. “The transition, in other words, is fooling no one,” said Adi Ignatius in Time. Yet Russians apparently don’t care. After the malaise and economic chaos of the Yeltsin years, they’ve welcomed the anti-Western bombast and especially the vast oil and gas revenues that have flowed on Putin’s watch. It’s a devil’s bargain: “There will be no democracy, but if you behave, we will give you opportunities to get wealthy.”

Don’t expect any changes under Medvedev, said David Remnick in The New Yorker. Some optimists, noting that the soft-spoken former law professor practices yoga and likes tropical fish, think he’ll be more moderate than his suspicious, steely patron. They should wake up. Medvedev is Putin’s “junior partner,” chosen for his ability to execute his mentor’s wishes. He’s not positioned to be a reformer; Putin has “eliminated or co-opted” all possible opposition, and Medvedev has no power base of his own, in either the military or the security apparatus. “With time, Medvedev may become his own man, but there is no real sign that he will alter Putin’s legacy.”

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Still, anything could happen, said The Christian Science Monitor. “Shared leadership is something new for Russia,” and it’s not certain that the Kremlin will continue to march to Putin’s drumbeat once he’s stepped down. For what it’s worth, Medvedev is talking openly of genuine change, pledging to fight corruption, criticizing Russia’s “legal nihilism,” and even endorsing “freedom in all its forms.” It remains to be seen, of course, whether such words reflect genuine convictions. Until now, Medvedev has been “Putin’s lap dog.” The question is whether he “will eventually leap to the ground and discover his own legs.”

The U.S. can’t afford to sit on the sidelines while Russia sorts this all out, said The Washington Post. There’s more at stake here than democracy and human rights. Under Putin, Russia has become a genuine regional concern. It has threatened to target Ukraine and Poland with nukes, bullied Georgia, encouraged Serbian extremists, “and tried to use its control over oil and gas pipelines to Europe as a political weapon.” The West needs Russia’s help to deal with Iran, arms control, and other challenges. At the same time, though, we should stop indulging Russia with G-8 membership and special relationships with NATO and the E.U. An “increasingly belligerent police state” such as Russia need not be treated “as an equal by the world’s leading democracies.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

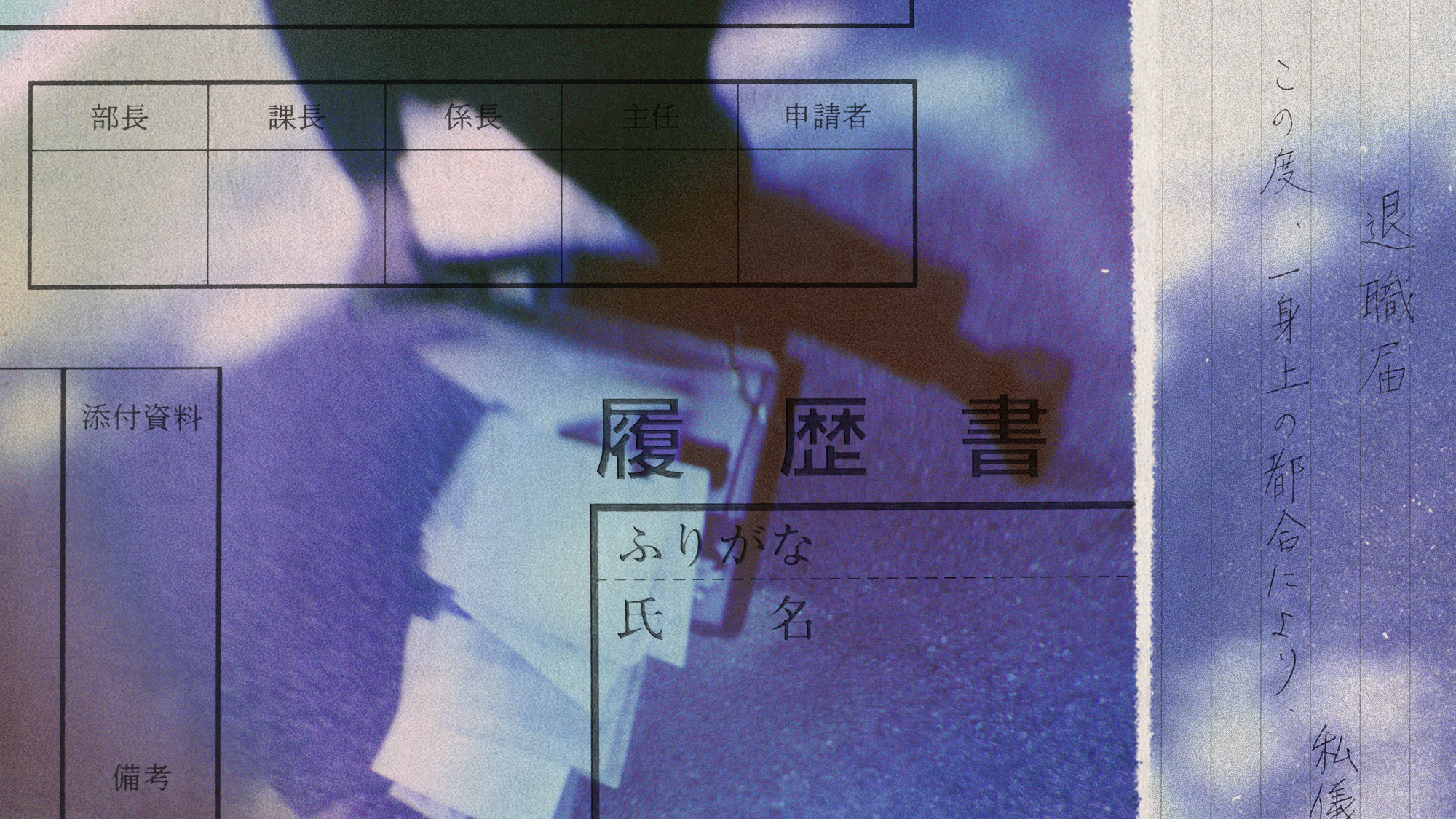

Why quitting your job is so difficult in Japan

Why quitting your job is so difficult in JapanUnder the Radar Reluctance to change job and rise of ‘proxy quitters’ is a reaction to Japan’s ‘rigid’ labour market – but there are signs of change

-

Gavin Newsom and Dr. Oz feud over fraud allegations

Gavin Newsom and Dr. Oz feud over fraud allegationsIn the Spotlight Newsom called Oz’s behavior ‘baseless and racist’

-

‘Admin night’: the TikTok trend turning paperwork into a party

‘Admin night’: the TikTok trend turning paperwork into a partyThe Explainer Grab your friends and make a night of tackling the most boring tasks

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred