The Democrats finally get it: It's the wages, stupid

Liberal policy-makers are starting to turn economic populism into policy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Now that the American jobs machine has finally hit second gear, economic commentators are starting to focus on wages more than headline jobs numbers. Despite the fact that 2014 was the best year for job creation since 1999, wages barely budged — indeed, they actually experienced a monthly decline last December.

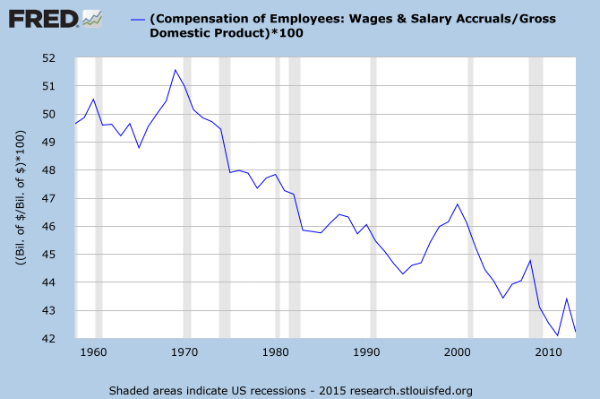

Wages are a good thing to focus on. But while some wage gains may be made as the economy slowly heats up, there is no reason to expect that long-term wage stagnation will be lifted by the invisible hand of labor markets alone, as Mark Thoma argues. Wages as a share of the economy have been falling for over 40 years, and it would be impossible to run a hot economy for the length of time needed to reverse the trend.

Only transfer policy, i.e. money distributed by the government, can make a dent in the major problem of most Americans being cut out of economic growth — and a new plan from House Democrats contains some promising moves in this direction.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The wage share of the economy has been falling on basically a straight trajectory since 1969. One school of thought says that running the economy hot is the way to combat this problem. If labor markets are tight, with lots of vacancies and few unemployed people, then workers will be able to bargain for better wages, and the wage share will increase.

This does work! Just not for very long. If we examine the wage share of GDP, we can see periods of economic strength coinciding with an uptick in the wage share. The problem is that the gains are quickly wiped out. In the red-hot economy of the late 90s, wages gained 2.8 percentage points of GDP; but then there was a financial crisis, and they lost 3.4 points. In the weaker Bush expansion, they gained 1.4 points; but then there was a financial crisis, and they lost 2.7 points. Our current pathetic state can be seen at the bottom right of this chart:

During the later Clinton years, from 1996 to 2000, wages gained an average of 0.53 points of GDP every year. If we treat that as an upper limit to how hot we can run the economy, we’d have to keep that blistering pace going for roughly 11 consecutive years to even match the levels of 1980.

There is basically zero chance that rate could be sustained for that long before a recession hit. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine that we can even hit that rate at all, let alone maintain it. Since 2008, growth has been extremely sluggish and wages stuck in neutral — we’re six years into the recovery and jobs are just starting to be created with any momentum. It’s time to move past wages as the only source of economic security for average people. It’s time to boost non-wage income.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Now, this is not to say that full employment should not also be a goal of economic policy (it should). On the contrary, transfers reinforce full employment. By putting purchasing power into the hands of people likely to spend it, demand, growth, and job creation will be strengthened, and marginal workers will be pulled into the labor market.

That’s why the new plan from House Democrats is so encouraging. It seems they are finally beginning to internalize the fact that American workers have been left behind for over a generation, and proposing the kind of brute-force transfer policies that could actually make a difference. This “action plan,” outlined by Rep. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.), includes a $1,000 tax cut for workers making less than $100,000 a year, incentives for corporations to share with employees the benefits of productivity increases, a boost in the child tax credit, and a few other goodies for the lower- to middle-class, all paid for by an increase in taxes on capital income, particularly a financial transactions tax.

I’d prefer that these policies came through straightforward transfers rather than hiding them in the tax code, but this is a massive improvement over typical milquetoast Democratic policy. The bottom half of the income distribution ladder doesn’t have enough money, so we should give them some. Simple as that.

In particular, as Ed Kilgore notes, it’s very encouraging that this is coming from Van Hollen, a fairly centrist character with close ties to the Democratic leadership — not a member of the Congressional Progressive Caucus. It suggests that the party is figuring out what I’ve been arguing for months: that bold economic populism, centered on huge transfer programs, is the optimal way for Democrats to get the electoral victories they need to govern.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.