What is vocal fry?

Kim Kardashian does it. So did the ancient Mayans.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

You may have heard of the hot new linguistic fad that's creeping into U.S. speech and undermining your job chances. Or maybe you know it as the debilitating speaking disorder afflicting North American women or the verbal tic of doom. It's called vocal fry, and it's the latest "uptalk" or "valleyspeak," AKA the "ditzy girl" speaking style that people love to hate.

Unlike uptalk, which is a rising intonation pattern, or valleyspeak, which covers a general grab bag of linguistic features, including vocabulary, vocal fry describes a specific sound quality caused by the movement of the vocal folds. In regular speaking mode, the vocal folds rapidly vibrate between a more open and more closed position as the air passes through. In vocal fry, the vocal folds are shortened and slack so they close together completely and pop back open, with a little jitter, as the air comes through. That popping, jittery effect gives it a characteristic sizzling or frying sound. (I haven't been able to establish that that's how fry got its name, but that's the story you hear most often.)

Vocal fry, which has also been called creaky voice, laryngealization, glottal fry, glottal scrape, click, pulse register, and Strohbass (straw bass), has been discussed in musical and clinical literature since at least the middle of the 20th century. It is a technique (not necessarily encouraged) that lets a singer go to a lower pitch than they would otherwise be capable of. It shows up with some medical conditions affecting the voice box. It is also an important feature in some languages, like Zapotec Mayan, where fry can mark the distinction between two different vowels. These days, however, you mostly hear about it as a social phenomenon, as described (and decried) as "the way a Kardashian speaks" in this video by Faith Salie.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Certainly, a compilation like this makes vocal fry look like a new thing, but looks can be deceiving. As Mark Liberman showed at Language Log, evidence for its rise is only anecdotal, and it's not hard to find examples of it going way back. People's voices naturally drop in pitch at the end of phrases, and in many speakers, it will drop into the fry zone at that point. The evidence that it's a female thing is also anecdotal. Plenty of men fall into vocal fry. For instance, Noam Chomsky has it pretty bad.

No one seems to be complaining that Chomsky's creaky voice makes him sound ditzy. Whether or not vocal fry is actually on the rise, it is clear that people noticing fry, especially in young women, is on the rise. In a recent segment on This American Life, Ira Glass said "listeners have always complained about young women reporting on our show. They used to complain about reporters using the word like and about upspeak…But we don't get many emails like that anymore. People who don't like listening to young women on the radio have moved on to vocal fry."

Glass talked to linguist Penny Eckert, who did a study asking people to rate how authoritative a radio reporter with vocal fry sounded. The response depended on the age of the rater. Those under 40 thought it sounded authoritative while those over 40 did not. Basically, as summed up by Glass, "if people are having a problem with these reporters on the radio, what it means is they're old."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Arika Okrent is editor-at-large at TheWeek.com and a frequent contributor to Mental Floss. She is the author of In the Land of Invented Languages, a history of the attempt to build a better language. She holds a doctorate in linguistics and a first-level certification in Klingon. Follow her on Twitter.

-

Gisèle Pelicot’s ‘extraordinarily courageous’ memoir is a ‘compelling’ read

Gisèle Pelicot’s ‘extraordinarily courageous’ memoir is a ‘compelling’ readIn the Spotlight A Hymn to Life is a ‘riveting’ account of Pelicot’s ordeal and a ‘rousing feminist manifesto’

-

The EU’s war on fast fashion

The EU’s war on fast fashionIn the Spotlight Bloc launches investigation into Shein over sale of weapons and ‘childlike’ sex dolls, alongside efforts to tax e-commerce giants and combat textile waste

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

10 signature foods with borrowed names

10 signature foods with borrowed namesThe Explainer Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

-

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged cultureThe Explainer We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

-

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous authorThe Explainer The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

-

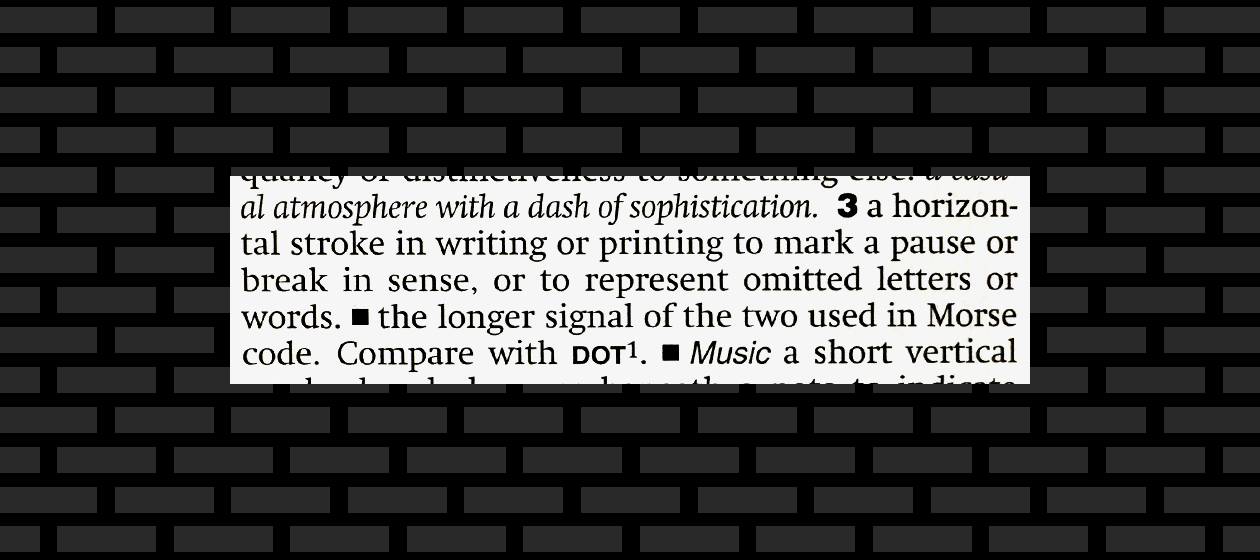

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guideThe Explainer Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.