Why Americans are so nostalgic about the manufacturing industry

Manufacturing has become a metonym for a broadly shared prosperity

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The fate of American manufacturing is back in the headlines, thanks to the bipartisan slugfest going on over the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the massive trade deal that has become a source of conflict between President Obama and Democrats in Congress.

On Monday, Matt Yglesias did his Matt Yglesias thing, and pointed out that, contrary to a lot of narratives about the decline of U.S. manufacturing, the sector's production is actually at an all-time high. It may have declined as a share of the country's overall economic production, but that's just because other sectors like health care and education have gotten bigger in comparison — not because manufacturing has shrunk.

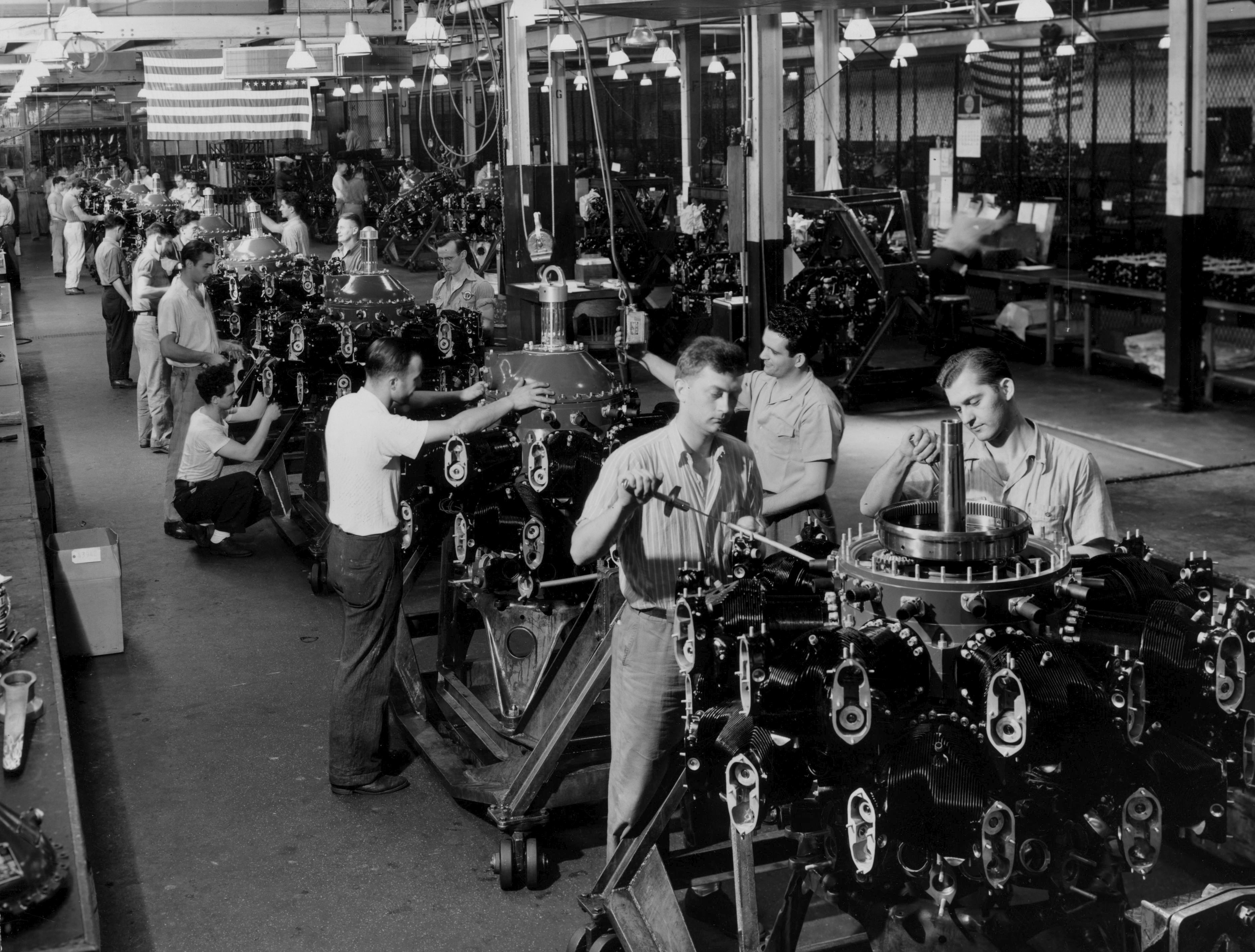

"One source of the misunderstanding," Yglesias noted, "is that manufacturing jobs really have disappeared" — dropping from about a third of all jobs in the 1950s to a little under 10 percent today. That's mainly a story of growing automation and productivity gains; we can just make way more per worker now.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The other source is more interesting: The U.S. still manufactures a lot of stuff, but most of it isn't stuff average American consumers buy. These days, we mostly make heavy industrial equipment, circuitry, aircraft, and other big and expensive goods and high-end products. These also constitute more than two-thirds of the manufactured goods we export, while about half of the manufactured goods we import are things like cars, food, beverages, clothing, jewelry, electronics, and other consumer goods.

Like the proverbial blind man who grabs an elephant's tail and assumes he's laid hold of a snake, Americans see the parts of the manufacturing economy they have immediate experience with — how many jobs it provides, the stuff they buy — and assume U.S. manufacturing is in decline.

Now, just as a matter of common sense, it's important to keep your data straight. So Yglesias is right to keep pointing out that manufacturing production is actually doing just fine in this country.

But allow me to put in a word in defense of the Americans who are grabbing an elephant's tail and think it's a snake.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The vast majority of voters — and the vast majority of politicians who try to translate what they hear from those voters into digestible political narratives — are not economists. They don't think in strictly "economic" terms. When they worry that manufacturing is declining, it's probably not because they think it's harming GDP growth, or because they think there's a better mix of industrial sector strengths, or some other macroeconomic claim. What they're arguably saying is something like: "This aspect of the economy was really important to the livelihoods of my family, friends, and community. And now it's dying." They're making something closer to an argument about the health of the social fabric.

As I've said before, I think we in the wonkosphere tend to fall into the trap of thinking of the economy as some sort of free-floating phenomenon that exists to serve its own ends. We note that manufacturing output is not in decline, that productivity and GDP growth seem to be okay, and then we go on with our day. But that's incomplete. The economy is here to serve people; to make their lives better; to do useful things for us and to give us something useful to do.

Admittedly, on the "do useful things for us" front, the changes in manufacturing in the last 40 years are pretty defensible. A lot of manufacturing went overseas because goods could be produced more cheaply there. So we get imports for a lower cost, which improves our standard of living. People in other, less developed nations get new jobs, which (assuming labor standards are up to par, which they often aren't) improves theirs. A win-win, theoretically speaking.

Same goes for rising automation: How could it possibly be a bad thing that we're able to create more wealth with less toil?

But the 1950s economy was also a delicately balanced ecosystem. The U.S. economy was relatively insular. Americans traded with other Americans, and bought their products from other Americans. And American firms generally competed with other American firms. Along with some robust government intervention and pressure from a still-powerful union movement, this created an environment where wages were good, health and pension benefits were plentiful, and job security was high. Manufacturing, as a third of employment, was a key part of that.

And then globalization happened, and all that went away. But that wasn't just some unfortunate event that was out of everyone's hands, like a meteor strike. The arrival of globalization gave certain interests and centers of power in our society the wedge and hammer they needed to break up the old arrangement. Unions became far weaker, business owners and management got much freer hands, and worker bargaining power collapsed.

The economic benefits of cheaper imported goods weren't broadly shared, because policymakers used globalization to put lower-class Americans in competition with foreign workers, but not upper-class Americans. Roughly the same outcome came from the benefits of innovation: Instead of the additional productivity leading to a drop in working hours for everyone, it led to a significantly bigger chunk of the overall income produced by the economy going into the pockets of the people at its very top echelons.

That result wasn't inevitable. Other Western countries also endured globalization, but managed to keep their levels of inequality lower — both before and after you count taxes and transfer programs. They also often took much more proactive approaches to the partnership between government and labor unions, resulting in friendlier labor policies and robust and surviving union membership.

Another lesson is probably that, with its more limited government and smaller safety net, the 1950s prosperity was a lot more precarious than it appeared, and the U.S. was always poorly positioned to endure globalization.

Ultimately, what people miss about manufacturing is the role it played in ensuring broadly shared prosperity. If we'd found some sort of alternative economic strategy for producing those same results, it's unlikely voters or politicians would be nostalgically lamenting any decline.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.