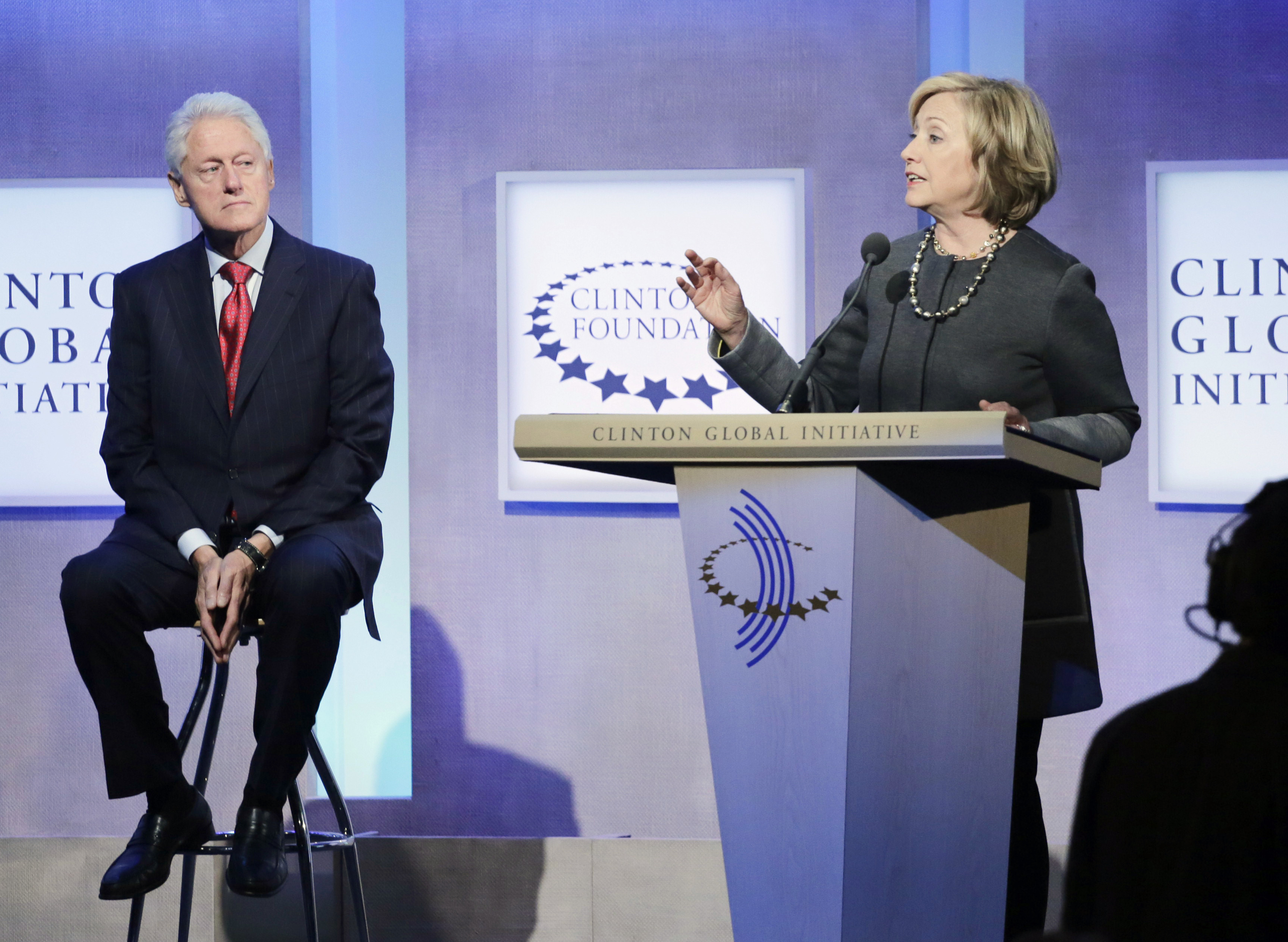

The Clintons' controversial foundation

Bill and Hillary Clinton's philanthropic empire has spent billions on good causes, but now faces questions about its finances

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Bill and Hillary Clinton's philanthropic empire has spent billions on good causes, but now faces questions about its finances. Here's everything you need to know:

What does the Clinton Foundation do?

It's an international philanthropy that mobilizes wealthy power players — individuals, corporations, and governments — to solve global problems. So far, the foundation has raised more than $2 billion for an eclectic range of programs, including fighting elephant poaching, improving schools here and abroad, and lowering the cost of AIDS drugs for 10 million people in 70 countries. Its financial model is simple: Converting Bill and Hillary Clinton's singular celebrity and influence into vast amounts of cash. It has succeeded spectacularly in that effort — but with poor transparency and many possible conflicts of interest. Some of the same foreign governments and corporations that donated to the foundation while Hillary Clinton was secretary of state also hired Bill Clinton to give speeches, and sought State Department approval for contracts and arms deals. The Clintons deny any wrongdoing, but many independent critics say the mixing of private and charity monies and apparent conflicts of interest are inexcusable. "It seems like the Clinton Foundation operates as a slush fund," says Bill Allison, a senior fellow at the Sunlight Foundation, a nonpartisan watchdog group.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How did the foundation begin?

As a way for Bill Clinton to fight off post-presidential boredom. Once the Clintons left the White House, Hillary Clinton launched her own political career, and in 2001 she was elected U.S. senator from New York. The former president often found himself home alone in Chappaqua, New York, watching TV. Looking for a way to get involved in public issues, the ex-president moved his offices to Harlem and met with a rock star's reception. Reinvigorated, he formed the William J. Clinton Foundation to develop programs to assist Harlem students and small businesses. In 2002, Clinton attended an AIDS conference, where Nelson Mandela reminded him that he had promised to "do something for Africa." Clinton's response was to launch a program to provide AIDS drugs on that continent. Then came a turning point: In 2004, Clinton staffer Doug Band suggested the boss should hold an annual meeting where the best and brightest — and richest — could brainstorm the world's problems. That idea turned into the Clinton Global Initiative, convened for the first time in September 2005. With the former president serving as its charismatic goodwill ambassador, the event drew a who's who of world leaders, business titans, and entertainment figures, and quickly evolved into a major organization with several arms.

When did it become controversial?

Questions have been raised all along. But a furor erupted in May, when conservative writer Peter Schweizer delved into the foundation's finances in depth in his book Clinton Cash. Schweizer also shared some of his findings with The New York Times and The Washington Post, which did further reporting. Though he admits he has no evidence of any explicit quid pro quo arrangements, Schweizer charges that the Clintons leveraged Hillary's government position — and possible future presidency — to coax donors into making huge contributions to the foundation. At the same time, Bill has personally received at least $26 million in speaking fees from donors to the foundation. "They created an apparatus that allowed them to get around prohibitions on foreign entities influencing our political process," Schweizer says. Meanwhile, people and governments who donated to the foundation often saw good things happen to their own interests.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Such as?

In 2005, for example, Canadian mining magnate Frank Giustra joined Bill Clinton on a trip to Kazakhstan. There, Giustra and Clinton dined with the country's dictatorial president, Nursultan Nazarbayev. Within days, Giustra acquired uranium interests in Kazakhstan that he later turned into a financial bonanza. The next year, he donated $31 million to the foundation. Eventually, Giustra sold off his uranium company to Russia's nuclear agency, Rosatom. The sale included some American uranium mines, which meant Hillary Clinton, by then secretary of state, was one of the people who had to sign off on the deal.

What about foreign governments?

The Clinton Foundation boasts a lengthy list of foreign donors. Under an ethics agreement Hillary Clinton made with the Obama administration, that cash flow was allowed to continue while she served as secretary of state, as long as donations were properly reported — a condition that was not met. One gift not reported was a $500,000 donation from Algeria. Shortly thereafter, the Algerians won a 70 percent boost in military export authorizations for items including chemical and biological agents.

Did other countries get similar boosts?

Yes. Overall, Hillary Clinton oversaw the approval of $316 billion in arms sales to 20 donor countries — a more than 100 percent increase in sales to those nations over the levels they received during the Bush years. "Can it really be that the Clintons didn't recognize the questions these transactions would raise?" asks Lawrence Lessig, director of Harvard's Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics. In response to the critics, Bill Clinton says "we have never done anything knowingly inappropriate," and points to the good the foundation has done. "I don't think there's anything sinister in trying to get wealthy people, and countries that are seriously involved in development, to spend their money wisely in a way that helps poor people."

Pals on the payroll

Unlike most charities, the Clinton Foundation doesn't dole out grants — it uses its donations to pay a staff of 2,000 to carry out humanitarian work. More than a few of those well-paid employees are longtime Clinton friends, supporters, and operatives with deep roots in the couple's political machine. Donna Shalala, who was Health and Human Services secretary under President Clinton, recently signed on as president and CEO. Chelsea Clinton now holds the title of foundation vice chair. Huma Abedin, one of Hillary Clinton's top aides and wife of former New York congressman Anthony Weiner, is also on staff. Longtime adviser and confidant Sidney Blumenthal recently concluded four years on the payroll, drawing $10,000 a month to help with research and "message guidance."