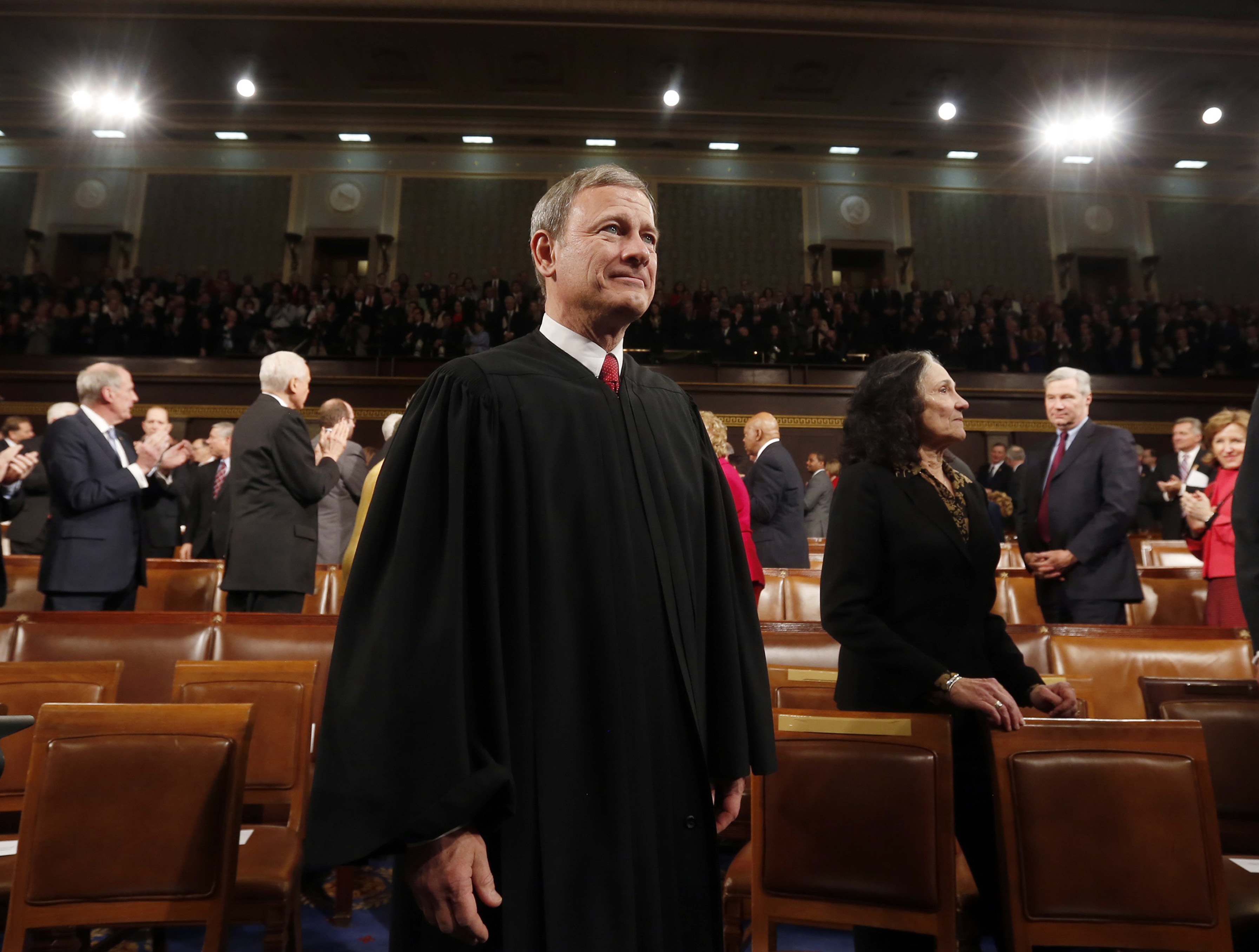

John Roberts, liberal hero: How the chief justice destroyed the conservative case against ObamaCare

Roberts shows that ObamaCare is the most conservative option for a universal health care policy

Since ObamaCare passed in 2010, Republicans have been searching desperately for a way to destroy the law through legal trickery (or as they call it, "judicial activism"), since they don't have the means to kill it through legislation. In 2012, with the Supreme Court decision NFIB v. Sebelius, they got a partial victory, with the court badly wounding the law's Medicaid expansion but leaving the rest unharmed.

In the case decided on Thursday, King v. Burwell, conservatives sought to cripple the insurance markets in states that had not set up their own health care exchanges. They did this by advancing a spurious reading of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that would forbid insurance subsidies from flowing through the federal exchange website, thus devastating the private insurance markets in those states.

This time, conservatives lost outright. Chief Justice John Roberts, joined by Justice Anthony Kennedy and the four liberals on the bench, wrote the opinion — and it delivers a stark rebuke to the conservatives who have been fumbling around for an alternative to ObamaCare since 2010. "Repeal and replace" has been their mantra, but they never even got close to uniting around an actual replacement policy. Today, Roberts shows us why: It's impossible.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

King focused on a single phrase in the ACA, "established by the State," which, taken out of all legal and policy context, could be construed to restrict subsidies to the state exchanges only. Because the Chevron doctrine requires that, in case of ambiguous wording, the implementing agencies get to decide how to interpret a law (in this case the IRS), it was necessary to construct an alternate history of the ACA. In this version, Congress meant to restrict subsidies to the state exchanges, to coerce states into creating one.

Liberals carefully explained that no, that was a completely insane version of ObamaCare's history. Health care policy reporters, the staffers who drafted the law, and members of Congress who voted for it all swore up and down that this had never even been seriously discussed, let alone that it was their intention. State-level politicians, who are responsible for deciding whether to create their own exchanges, reported they had never heard of such a threat. Why would Congress create a mechanism to force states to do something, and then never mention it?

Roberts' opinion delivers total victory to the liberal case. First, he examines the statute and finds that, in fact, it is not ambiguous — the government's interpretation is correct. He writes that, considered in context, the plaintiff's reading of "established by the State" would make great swathes of the rest of the law totally nonsensical. The ACA clearly states that all exchanges are to provide qualified plans to qualified people, which would be impossible for the federal exchange without subsidies. Moreover, why would the law provide for a creation of a federal exchange at all, if nobody can actually use it?

Second, and more fundamentally, Roberts finds that the plaintiff's reading of ACA is poles apart from the obvious policy intention of the law. He accurately describes ObamaCare's three-pronged approach: guaranteed issue and community rating, requiring insurance companies to offer policies to everyone at a reasonable price; an individual mandate, so that healthy people will participate in the risk pool; and subsidies for people who can't afford the insurance.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

All three are necessary for ObamaCare to work, but the plaintiffs' reading would eliminate two of the three prongs in states without their own exchange. Subsidies would go, and so would the individual mandate, because it doesn't apply if people are spending more than 8 percent of their income on a policy. Roberts notes that this would likely cause an insurance death spiral in those states, as healthier people flee an increasingly expensive market, turning the ACA into a health insurance doomsday device. Indeed, just such a death spiral happened in several states before ObamaCare passed — which is partly why it included all three prongs. "Congress passed the Affordable Care Act to improve health insurance markets, not to destroy them," he concludes.

That brings me to the "replacement" rhetoric. Roberts' clear account of ObamaCare's policy mechanism, and the damage that would be done should any of its main prongs be removed, deals a body blow to the conservative health care wonks who have been trying to cook up a replacement policy for the last five years — in particular, a plan without the unpopular individual mandate. But as Roberts plainly shows, that leads straight to disaster.

It's an implicit concession that ObamaCare is the most conservative possible policy that could get even close to universal coverage — if five years of Republican policy failure weren't enough evidence.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Which way will Trump go on Iran?

Which way will Trump go on Iran?Today’s Big Question Diplomatic talks set to be held in Turkey on Friday, but failure to reach an agreement could have ‘terrible’ global ramifications

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue TUI after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred