The missing factor from the great Federal Reserve debate: The 99 percent

Investors want the central bank to take away the punch bowl. But for most people, the party has barely begun.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Starting today, American monetary policy will get about as close as it ever does to high drama.

In response to the massive crash of 2008, the Federal Reserve drove interest rates down to basically zero, and they've stayed there ever since. That's an unprecedented run in the modern history of monetary policy, and there's been growing chatter that the Fed will bring it to a close following the two-day policy-making meeting that begins Wednesday. Yet that expectation hasn't quieted anyone down: Debates about whether Fed officials will raise rates, and whether it should raise them, are as intense as ever. And no one — including the Fed officials themselves — seems to have any idea what they'll ultimately decide.

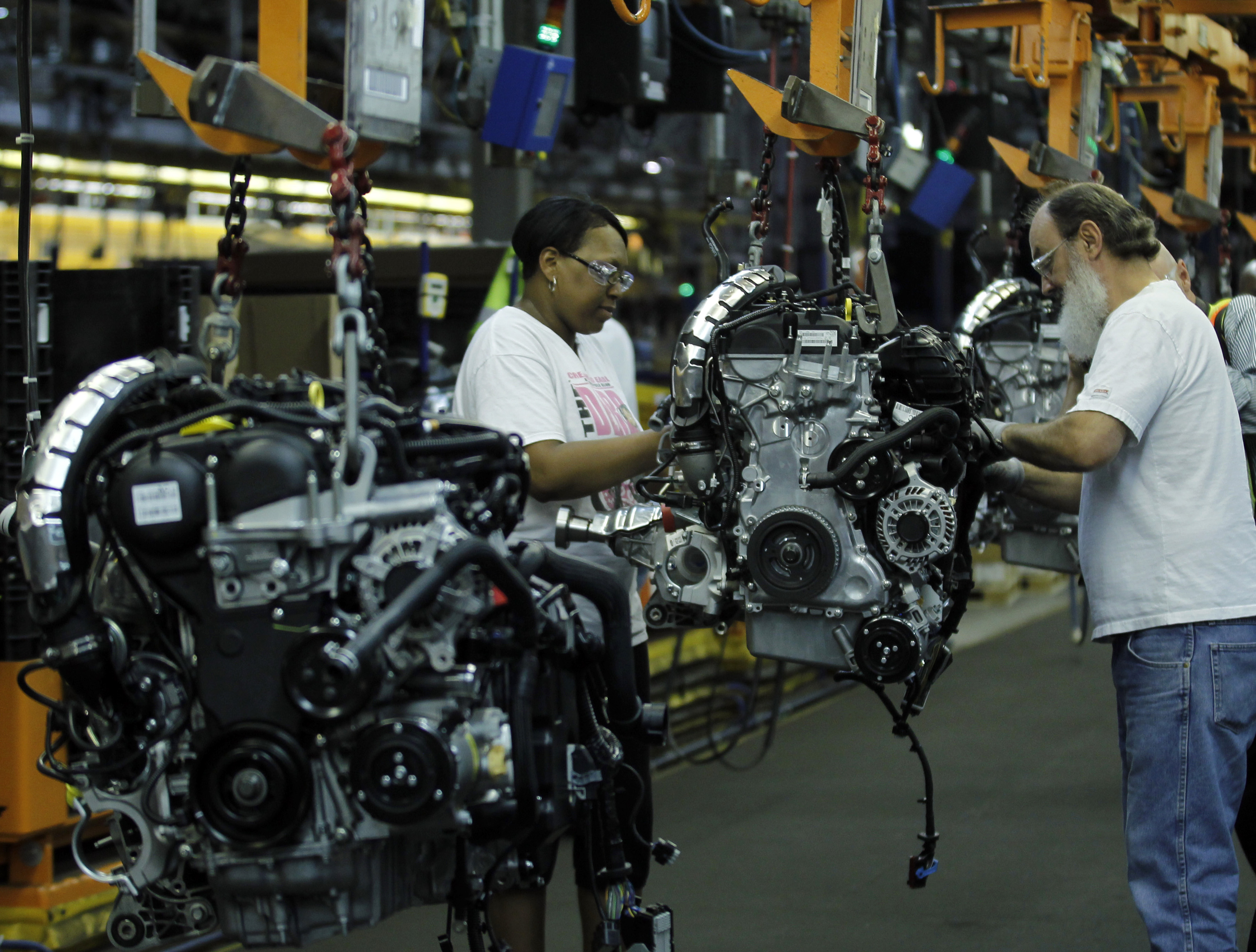

But all this drama, for the most part, is occurring within the small slice of the population that understands monetary policy and keeps an eye on it — one that's hardly representative of America writ large. Janitors, window washers, truck drivers, and most other everyday workers are not involved in the discussion. It's economists, think tanks, policymakers, financiers, top tier business leaders, and the related media outlets. And that can create a bias in how the issue gets discussed.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

For example, The New York Times just ran a piece on the Fed's upcoming decision, and on the possibility that this exceedingly long stretch of unusually low interest rates has encouraged a massive bull run, introducing lots of instabilities to the financial markets. Even a small hike by the Fed, the Times says, could start things unraveling.

The thing to realize is that this argument is often held up as one against low interest rates, i.e. the Fed should never have kept them this low in the first place, so now we're going to pay the price for its excess.

"The Fed is supposed to remove the punch bowl just as the party gets going,” said Albert Edwards, a strategist with Société Générale, in an email exchange. “It is already well past midnight, but the guests will keep partying until they drop if you ply them with even more alcohol." [The New York Times]

But let's dissect Mr. Edwards' analogy here. What is the "party" he is referring to? Presumably, it's the U.S. economy. But if that's the case, saying it's "already well past midnight" makes no sense.

The topline unemployment rate may be getting back down to the levels generally associated with full employment, but there are lots of reasons to think it's an untrustworthy metric. The U-6 unemployment rate, by contrast, includes the official unemployment rate, plus everyone who's working part-time but wants to be working full-time, and unemployed people who have looked for work within the last 12 months. (The official unemployment rate only counts people who have looked within the last four weeks. Longer than that, and you aren't counted as employed or unemployed.) In other words, the U-6 rate is arguably a better metric for how good a job the economy is doing at providing Americans the employment they need.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And at 10.3 percent, it only just got down to where it was at the worst part of the 2001 recession.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_large","fid":"129024","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"399","style":"display: block; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"600"}}]]

For comparison, the U-6 rate was 6.8 percent at the peak of the late '90s boom.

There are other signs of distress, too. Labor force participation — the employed plus the unemployed (looked in the last four weeks) as a portion of the overall population — is still way down from its peak before the 2008 recession. Of the overall population that's prime working age (25 to 54), 77 percent is employed — that's below the pre-2008 peak, which in turn was below the pre-2001 peak.

In short, from the standpoint of most American workers, this doesn't look like a party that's "already well past midnight." It looks like a party that's barely gotten started.

Of course, if you're a member of the financial and economic elite, the unemployment rate within your socioeconomic tribe is basement low. So you're unlikely to see a need to worry about that. But you've probably also noticed the signs of excess in financial markets that the Times piece pointed to: the probability that we're in a tech stock bubble, the rise of lending to companies with a lower credit rating, and the flood of stock buybacks. So for elites, you could imagine how it does look like the "party" is well into the early morning hours and getting a bit out of hand.

But that also makes it an example of the way inequality has warped our public discourse, with debates shaped entirely by the experiences of elites, and the experiences of less privileged Americans written out of the analysis entirely. What you have to remember is that what you see from the elite seats — namely the ups and downs of the financial markets — isn't the real economy most Americans rely on for the livelihood.

And as the Times story also admits, it's hard to see the ways the excesses in the financial economy could worm their way into the real one. The tech bubble is a lot more isolated to its specific sector than the 2001 boom was; when you account for inflation, corporate borrowing actually isn't unusually cheap; and it looks like the post-2008 financial reforms have brought toxic assets in sectors like real estate to heel. As for stock buybacks, they're a serious problem, but one created by tax and regulatory policy changes that have allowed elites to raid corporate revenues at the expense of workers. It seems strange to put the brakes on the whole economy to deal with that one issue.

That isn't to dismiss the risk of financial instability entirely, but simply so say it's extremely remote. On the flipside, we have a recovery that, seven years after the Great Recession, has only just started making serious headway. And there's the possibility that upping interest rates now could stall or reverse that progress.

Which is to say, it's not simply about managing risks, it's about weighing different kinds of risks. The risks to the elite of an interest rate hike are relatively mild. The risks to workers are much greater.

Before we worry about whether the party is getting out of hand, we should ask how many people even got to attend.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.