Jeb Bush's newest headache: Is his brother really to blame for 9/11?

Why we assign presidents blame for everything that happens under their watch

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Presidents, it is said, get too much credit when things go right and too much blame when things go wrong. Usually this aphorism comes up when we're talking about the economy, since the president is genuinely limited in what he can to do create or destroy prosperity. If it was completely within the president's control, we'd never have any economic downturns. But in every presidential election, the party in power gets rewarded if the economy is doing well and punished if it isn't.

We want to assign blame when things go wrong, to parcel out responsibility to all who deserve it. While it's usually incumbents who are dragged down by this impulse of voters, today it's Jeb Bush who seems crushed under the weight of all the disasters of his brother's presidency, even though none of them were Jeb's fault. First, he couldn't decide whether the Iraq War was a mistake. And now he's engaged in a bitter argument with Donald Trump about whether George W. should be blamed for the Sept. 11 attacks.

Trump argued that Dubya couldn't exactly be said to have "kept us safe," as Jeb has claimed, because he was, in fact, president when 9/11 happened. For his part, Jeb was aghast at the suggestion. "Does anybody actually blame my brother for the attacks on 9/11? If they do, they're totally marginalized in our society," Jeb told CNN's Jake Tapper. "It's what he did afterwards that mattered, and I'm proud of him." When Tapper followed up by asking whether, by that token, it's fair to blame Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton for the deaths of four Americans in the attack on the American consulate in Benghazi, Jeb seemed flummoxed, as though this had never occurred to him. Of course Hillary Clinton is (or at least might be) responsible for what happened at Benghazi, while of course his brother wasn't responsible for Sept. 11.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Blind partisanship aside, maybe the word "blame" is part of the problem. We sometimes imply that only one person can be blamed, but in truth blame can be spread widely, and there's nothing zero-sum about it — the fact that one person shares blame doesn't lessen the blame you might ascribe to someone else.

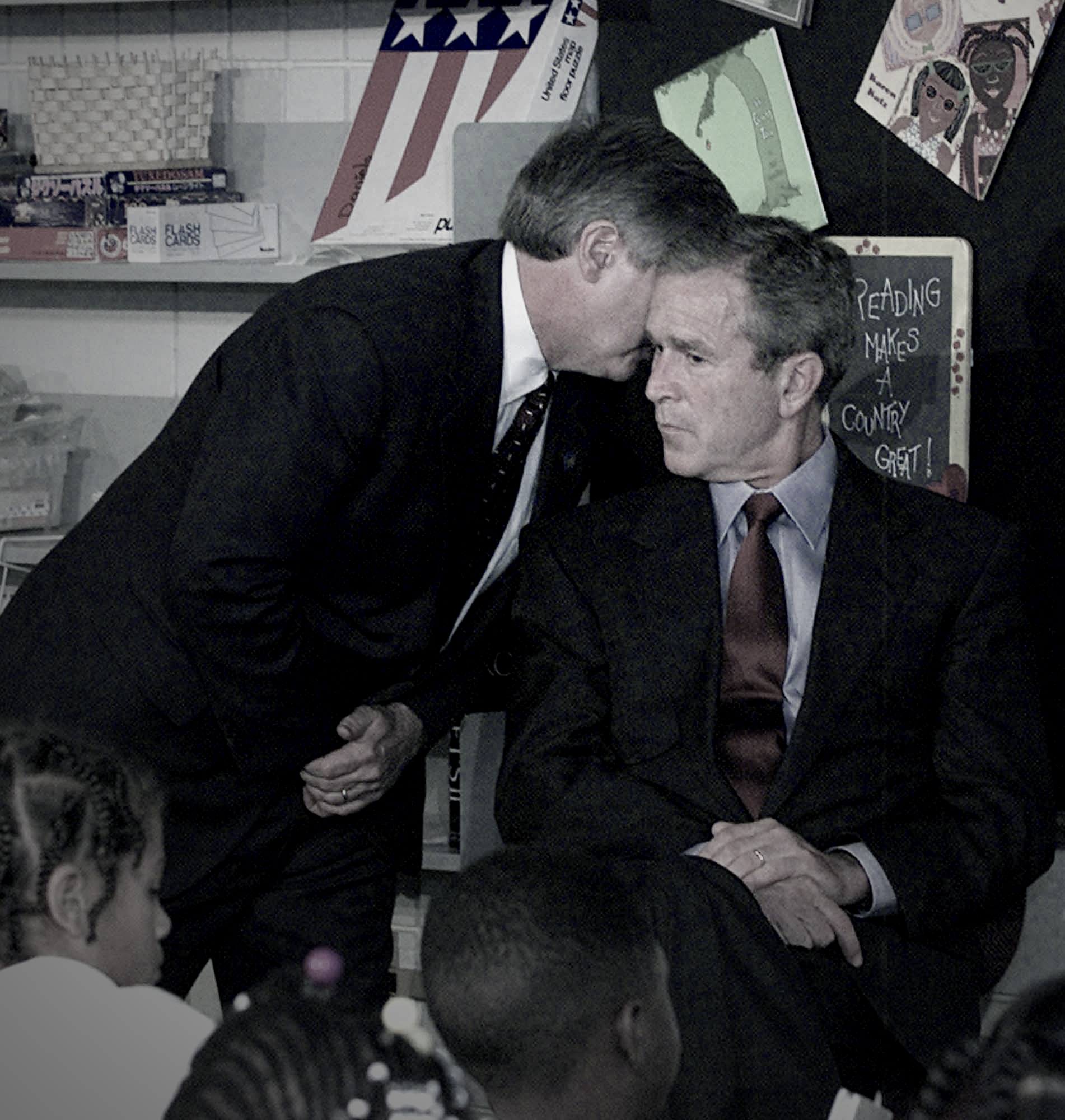

So you don't have to be a conspiracy theorist to accept that, as president, George W. Bush should shoulder some measure of responsibility for not stopping the Sept. 11 attacks, even if he had been commander-in-chief for only eight months. That's particularly true given that intelligence officials had been urgently warning him that al Qaeda was preparing some kind of significant attack, most famously with a briefing document he received a month before the attack headlined, "Bin Laden Determined to Strike in U.S."

Bush reportedly replied to his briefer, "All right. You've covered your ass, now," suggesting that he gave the al Qaeda threat something less than top priority. But what might he have done differently? And would it have stopped the attack? It's hard to say for sure.

On Benghazi, what has Republicans so frustrated, and what is turning their investigation into such a farce, is their inability to find a way to assign Hillary Clinton the blame for those four deaths. It's a problem of their own making, because from the outset they didn't argue that, as secretary of state, she bore ultimate responsibility for what happened on her watch. Instead, they were sure that she had committed some horrifying act of malfeasance or even criminality. Some in the more fevered quarters of the right still believe there was a "stand-down order," that Clinton or somebody else intentionally left those four Americans to die by telling the military not to go save them.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But there was no such thing, as has been confirmed by investigation after investigation, most of them conducted by Republicans who would have surely trumpeted it to the heavens had they discovered such a dastardly act. Having set the bar of blame so high, insisting that they would prove that Clinton had done things so shocking to the conscience that she would forever be cast out of public life, they're left with no blame to force upon her.

Benghazi, as terrible as it was, is a minor incident when placed against events like 9/11, which a different president might or might not have been able to stop, or the Iraq War, which a different president wouldn't have started. Benghazi touched very few American lives. But when something truly monumental goes wrong, somebody has to take the blame, and more often than not it'll be the president, whether he deserves it or not.

Perhaps that's partly because in campaign rhetoric, the president is practically omnipotent. Elect me, candidates say, and everything that's wrong today will be set right. Incomes will rise, crime will drop, foreign enemies will melt before us, your children will grow up smart and well-mannered with brighter teeth, and America will enter a glittering new age where all things are possible.

When we fail to enter that utopia, they say, "Look, it wasn't my fault." Even when they happen to be right, we don't believe them.

Paul Waldman is a senior writer with The American Prospect magazine and a blogger for The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in dozens of newspapers, magazines, and web sites, and he is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics.