China's one-child policy and the lessons for America

Let's review exactly what population has to do with economic growth

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

China's infamous one-child policy is no more.

The policy was instituted in 1979 — complete with "forced sterilizations and abortions, infanticide, and a dramatic gender imbalance" the Guardian reports — preventing an estimated 400 million births in the decades since. Ironically, the policy was inspired by paranoia that population growth would stifle the Chinese economy. Now it's getting scrapped out of concern that too little population growth will do the same. China's population is rapidly aging, meaning Chinese workers will have to support way more Chinese retirees over the next few decades.

You might be worried that the same thing is happening in America — that Social Security will be unsustainable as fewer U.S. workers have to pay for more and more Baby Boomer retirees. So let's review just what population has to do with economic growth. And why China's problems are not America's problems at all.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

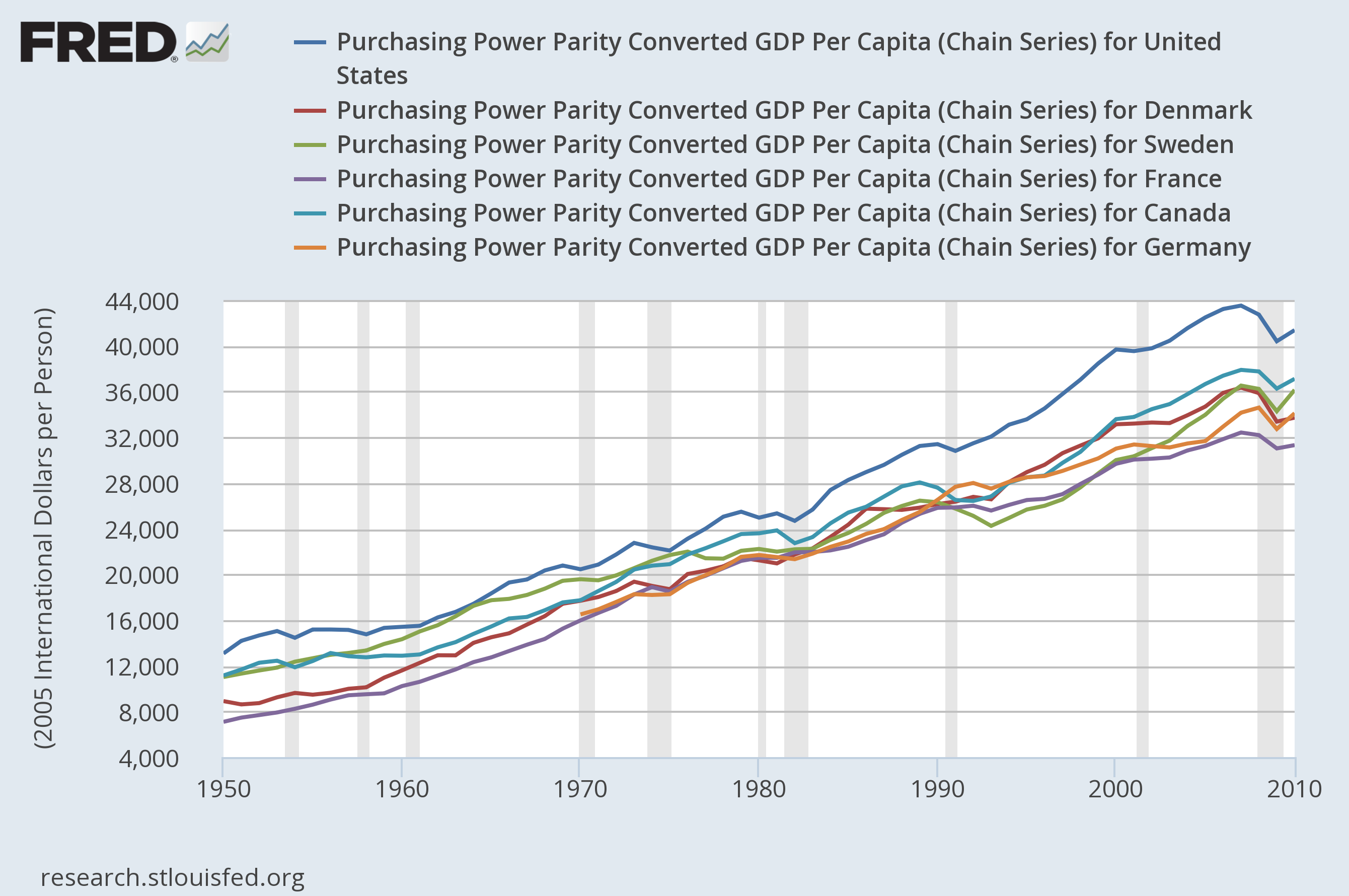

There's a brand of natalist enthusiasm in U.S. politics that insists more births are always better, because it drives up gross domestic product (GDP), among other things. But this isn't quite right. You really can't help but drive up GDP by adding new people, since each new person means more economic activity. So increases in a country's GDP due to population growth don't really tell you anything useful about how good that society is at creating wealth and being productive. We know there's more stuff, but is it better stuff? That's why GDP per capita is a much better metric. And it's one the U.S. still does quite well on:

If we distributed the annual income (and didn't adjust for inflation or international comparisons) evenly between every man, woman, and child in the country, they'd each get more than $54,000. And retirement is all about distributing incomes. If a portion of your population isn't working because they're old, but you still want them to have a decent standard of living, then by definition you have to take money from people who are working and give it to the old, not-working people instead. Hence the freakout that there will be just two workers per retiree in 2035. We're going to have to take more from each individual worker to support the Social Security and Medicare benefits that current retirees enjoy.

GDP per capita is a rough metric for how many nonworking people each working person can support, and at what standard of living. If America's GDP per capita was low, that would be a problem, because we'd be forcing everyone back to an equal level of impoverishment. It could also be a problem if our ratio of workers to retirees changed too much, too fast. Then we'd wind up forcing the living standards of workers to either stop rising, or to go down.

Happily, that's not happening either: Even if productivity increases by a measly 1 percent annually between now and 2035, that would raise living standards by 25 percent. Conversely, the drag of one retiree for every two workers will only lower living standards 10 percent. (Another way to put this is: At current benefit levels, Social Security will eventually go from 4.9 percent of GDP now to 6.3 percent in 2040.) Now, that presents a political problem of distribution: To keep all retirees at current benefit levels, living standards for everyone else will have to rise more slowly than they otherwise would. And younger, working people might not like that. But it's perfectly feasible in terms of raw economic sustainability.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

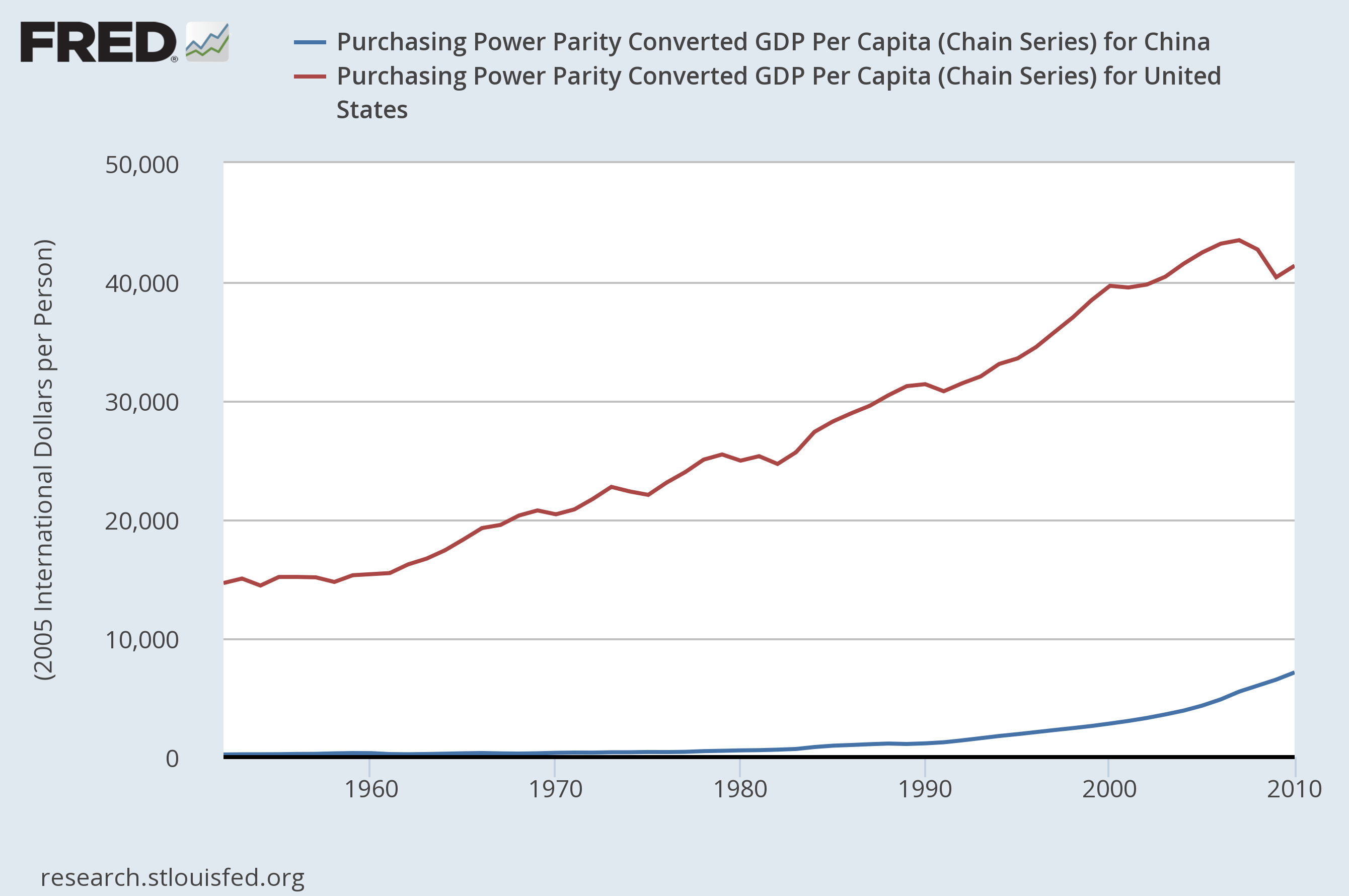

Let's now return to the case of China, and pinpoint just why China's increasing number of old people is a problem. Despite China's enormous total population — and resulting enormous GDP — their GDP per capita is still quite low.

If you took the total income created by the Chinese economy and spread it evenly between every man, woman, and child, everyone would still be pretty poor. China's GDP per capita provides its economy way less wiggle room than America has. That's why it's way more important for China to keep its retired population as small as possible relative to its working population. Hence the end of the one-child policy: More births mean more workers.

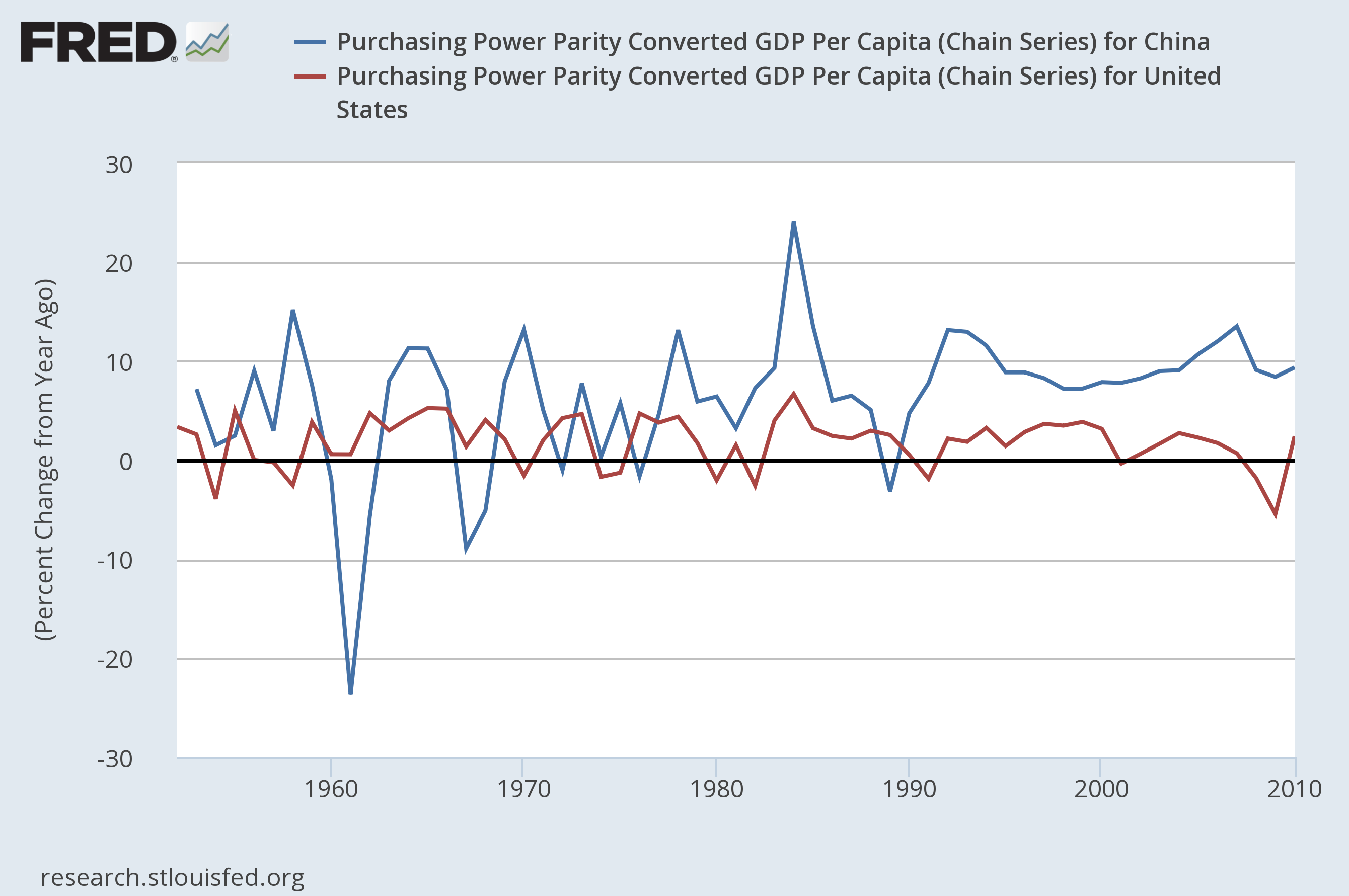

Now, one thing China has going in its favor is the rate at which its GDP per capita is growing:

That two-decade run of almost 10 percent growth, year after year, is the economic miracle that's lifted hundreds of millions of China's people out of poverty.

Unfortunately, the amount of people in China over age 60 is also growing really fast. It's expected to more than double as a share of the population over the next few decades, from 12.4 percent in 2010 to 28.1 percent in 2040 — the fastest such increase in the world, according to the United Nations. (For a rough contrast, Americans over 65 are projected to go from 13 percent of the population in 2010 to just 20.2 percent in 2050.) On top of that, China needs to transition away from an export-based manufacturing economy, and into a service-based economy. So it's not clear how long those high growth rates for GDP per capita can last: Every advanced Western country that's made that shift has seen their rate of GDP per capita growth drop.

Finally, despite that 400 million births number, it's just not clear how directly responsible the one-child policy was for China's low birth rate. Birth rates naturally drop as societies become wealthy and modernize, and especially as they bring their female populations into greater social, educational, and civic equality. That appears to be the main driver of China's low fertility.

Of course, on the level of simple human decency, China's abandonment of the one-child policy is a huge win. But the country still effectively has a two-child policy. Any Chinese family that wants more kids than that still faces quotas and surveillance and the possibility of forced abortions.

And in cold-blooded economic terms, China faces a real demographic problem. America's demographic problem is just a phantom conjured by politics and the culture war.

Ultimately, that's an argument for why China should liberalize and hop on the capitalism bandwagon. The experimental trial-and-error created by free markets really does seem to be the secret sauce that drives productivity and wealth creation — and thus GDP per capita. And plenty of Western countries do a much better job than America when it comes to distributing that bounty in a just and equitable fashion, both to their retirees and everyone else.

China can and should look to them as examples. But America needn't look to China as a cautionary tale.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy