Sorry, Bernie: A tie in Iowa is still a win for Hillary

Kudos to the Vermont senator for his come-from-behind near-victory. But math still counts, and not in Sanders' favor.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sen. Bernie Sanders is right. The Vermont independent may have lost the Iowa Democratic caucuses to Hillary Clinton by the narrowest of margins, but it really was a "virtual tie."

With 99.9 percent of precincts counted in Iowa, Clinton leads Sanders 49.9 percent to 49.5 percent. The Iowa Democratic Party said early Tuesday that the one outstanding precinct, in Des Moines, will award 2.28 state delegate equivalents, not enough to boost Sanders (695.49 SDEs) over Clinton (699.57 SDEs), even if he wins the final precinct. Clinton has declared victory, though Sanders has not yet conceded.

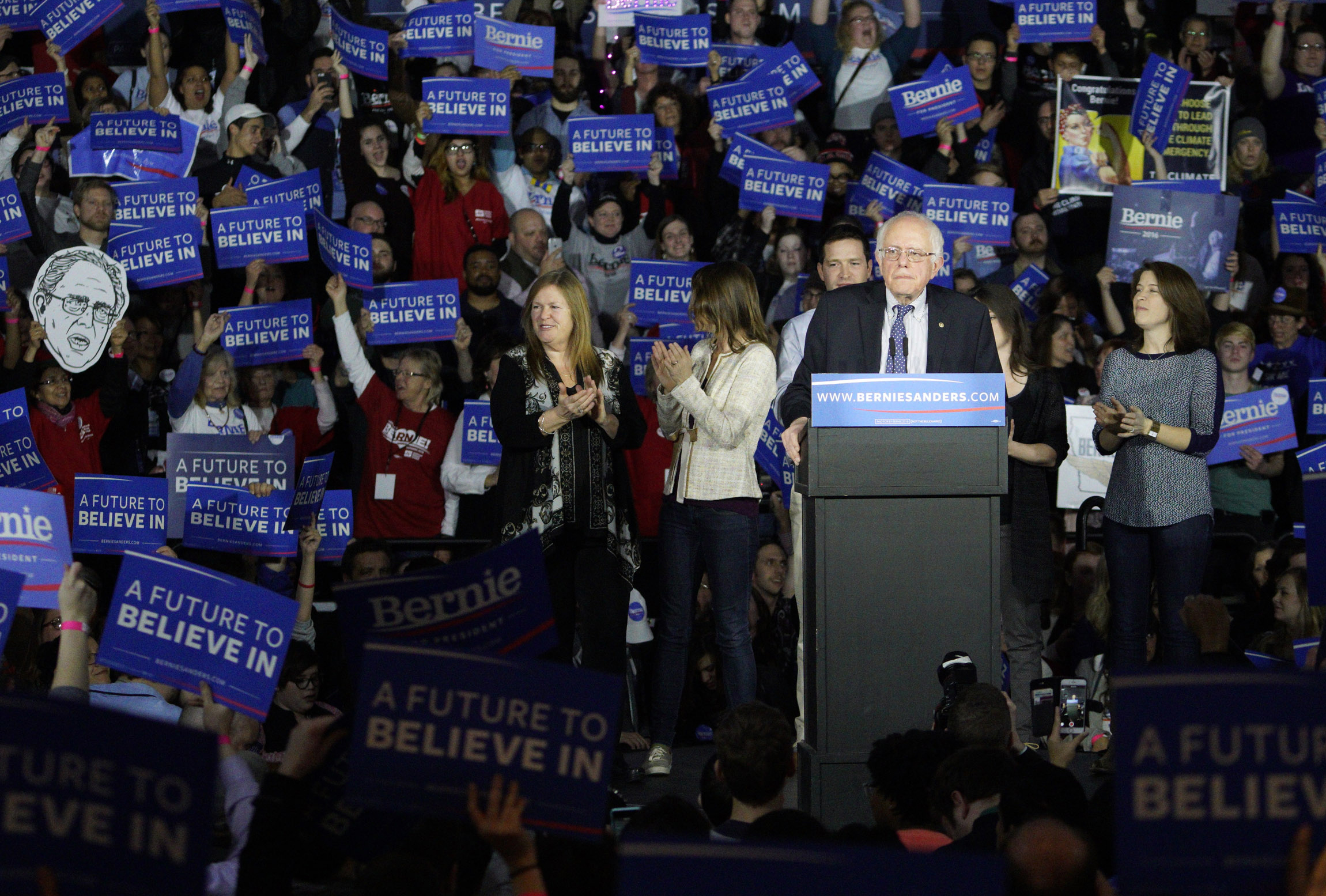

This result is as close as they come. And the photo finish is in many ways an impressive upset for Sanders, who told supporters Monday night that nine months ago he went up against the "the most powerful political organization in the United States of America" with no money and no campaign organization, and on Monday he wrestled it to a draw. The icing on the cake: Sanders is favored to win the next contest, in New Hampshire on Feb. 9.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As with horseshoes and hand grenades, close does count in tough primary fights like the one brewing between Clinton and Sanders. Momentum and beating expectations also matter, especially for the political scorekeepers in the news media, and Sanders can claim victories on both those metrics. But the fight for a party's presidential nomination really comes down to math — a fact Barack Obama's campaign drew on to defeat Clinton in 2008 — and a near-win in Iowa doesn't add up for Sanders.

The problem for Sanders is that his base of support is among white liberals, and "there is only one state where whites who self-identify as liberals make up a higher share of the Democratic primary electorate than Iowa and New Hampshire," said David Wasserman at the Cook Political Report. "You guessed it: Vermont." Clinton also has a massive lead in pledged superdelegates, who make up 15 percent of the Democratic delegates and aren't tied to state results.

Wasserman and the Cook team put together a chart with estimates of the number of delegates Clinton and Sanders would have to win in each state to be "on track" to win the Democratic nomination. The "key takeaway," he notes, is that "for Sanders to be 'on track' to break even in pledged delegates nationally, he wouldn't just need to win Iowa and New Hampshire by a hair. He would need to win 70 percent of Iowa's delegates and 63 percent of New Hampshire's delegates." In other words, Wasserman adds, "if Sanders prevails narrowly in Iowa or New Hampshire, his support among liberal whites and in college towns... would be entirely consistent with a scenario in which he also gets clobbered by Clinton nationally."

Sanders will win about 50 percent of Iowa delegates, or 21 delegates, according to a near-complete tally. Wassermann's chart suggests Sanders had to win 31 delegates to be on track to tie Clinton nationally. "When placed in the proper mathematical context," Wasserman concludes, "this year's Democratic primary remains a much steeper mountain for Sanders than many chroniclers of the campaign trail seem to realize or acknowledge."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

If you want to know why Clinton told supporters on Monday night that she's "breathing a sign of relief" over the Iowa results, that's probably why.

The ghosts of 2008 hang heavy over the Clinton operation. A loss in Iowa would have been a setback, an unwelcome reminder of her momentous defeat to Obama, but in 2008 Clinton didn't just lose to Obama — she also narrowly lost to John Edwards, coming in an inglorious third place. A win for Clinton this year would be a win, regardless of the margin.

More to the point, the Sanders campaign isn't a repeat of Obama 2008. Obama's decisive victory in Iowa expanded his base of liberal white voters by convincing black Democrats that he could actually win. Sanders hasn't shown yet that he can expand his pool of young, liberal, white supporters. As Charles Pierce argues persuasively in Esquire, Sanders 2016 is less like Obama 2008 than the 1984 and 1988 campaigns of Jesse Jackson — a candidate Sanders endorsed at the time — and the 2004 run by Howard Dean, a Vermonter like Sanders.

Jackson, Dean, and now Sanders all tapped into "a subversive, counter-establishment energy" in the Democratic Party that has "refused to be quelled," despite attempts to tamp it down by the party establishment, Pierce writes. "This old flow of counter-establishment energy... has been magnified by the frauds and crimes of the financial elites," he adds, but "it has been a continuous strain of activist politics, from Jesse Jackson to Bernie Sanders."

Neither Dean nor Jackson ever won the Democratic nomination — and, perhaps ominously for Clinton, the Democrats lost in 1984, 1988, and 2004. But they did push the eventual Democratic candidates to the left, making their marks on the party and its platform. Sanders appears to have already accomplished a similar feat with Clinton.

Sanders has the resources and popular enthusiasm behind him to give Clinton a run for her money. And given the unpredictable nature of this race, the anti-establishment fervor in the country, and the ever-lurking Clinton email situation, Sanders might even pull together enough delegates to win the Democratic nomination.

But he needed a solid win in Iowa to shift the fundamental dynamics of the race. He certainly did not get that. And that makes Iowa a win for Hillary Clinton.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred