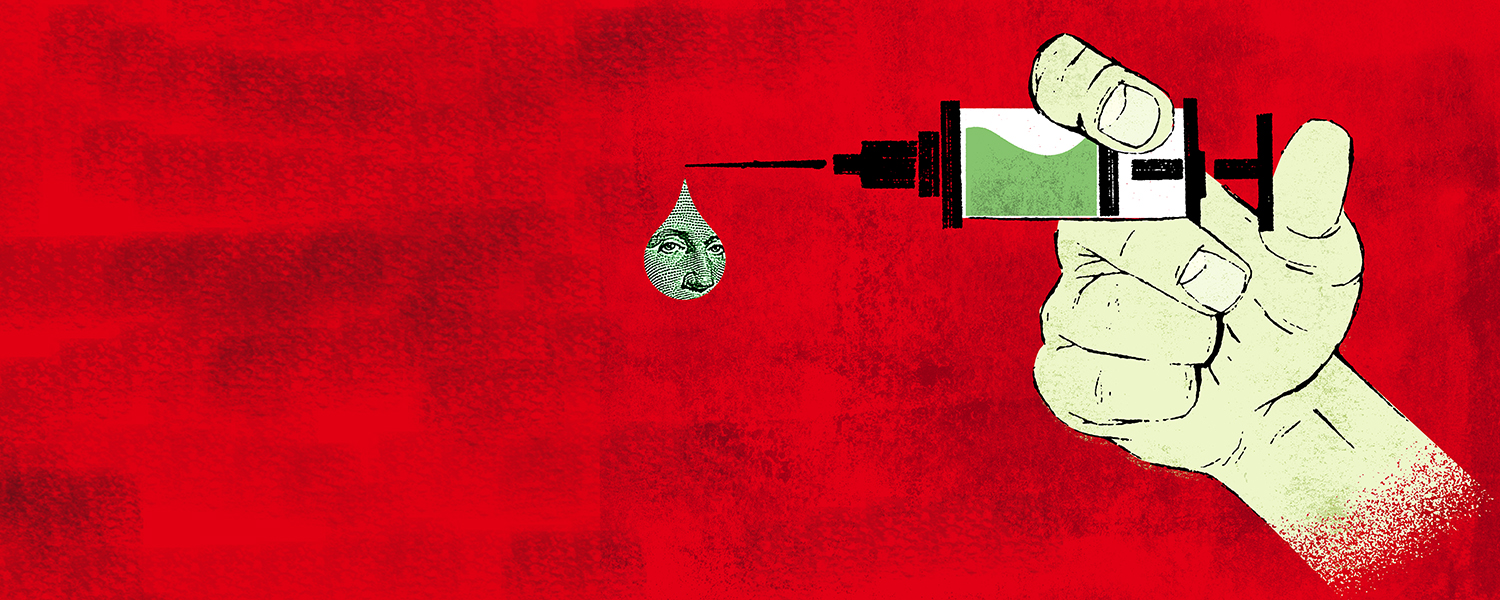

This is the progressive budget that Democrats have been waiting for

Why liberals should rally behind the Congressional Progressive Caucus' latest budget

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It's springtime, which means it must be federal budget season again.

One of the more interesting spectacles to emerge from this process in the last few years was the annual budget proposal put together by one Paul Ryan in 2014. It would've sliced an eye-popping $4.8 trillion over 10 years out of all government spending other than defense, with two-thirds of the cuts coming from programs that serve the poorest and most vulnerable Americans.

Today, as speaker of the House, Ryan finds his efforts to negotiate a workable budget with the White House stymied by the House GOP's hard-right members. But in its heyday, his budget gave the conservative movement a comprehensive policy vision to organize around.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

If you think uniting behind this kind of banner proposal is a strategy Democrats and liberals should emulate, you'd be right. In fact, they may already have one on hand: The budget from the Congressional Progressive Caucus (CPC), a.k.a. "the people's budget." They've been proposing it for several years running, but a new analysis of its latest iteration by the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) shows what a rallying cry it could be.

The budget's ultimate goal is "to push unemployment to 4 percent," Hunter Blair, a budget analyst at EPI, explained to The Week. It accomplishes this by fighting back hard against the kind of austerity Ryan champions.

The CPC budget bulks up funding for food stamps, child nutrition programs, Medicaid, and unemployment insurance, along with housing assistance for low-income families. It indexes Social Security to a more generous cost-of-living measure, so benefits increase more over time. It expands both the earned income tax credit and the child tax credit, which top-off the paychecks for poorer Americans with extra cash. And it appropriates federal funding to create either national-level or state-level programs for paid sick leave and paid family leave.

Along with replenishing these preexisting welfare programs, it would push non-defense discretionary spending back up to its historical average of 3.5 percent of the economy by 2021, down from the historic lows of 2.3 to 2.4 percent it's at now. "In the long run [the CPC budget] spends a lot on needed public investments to push back against slowing productivity growth," Blair said.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But the CPC budget also contains some genuinely new additions: a public option for ObamaCare's exchanges, funding to provide preschool for all families, a new program to refinance student debt, and a change to the law to allow Medicare to negotiate drug prices with providers. But arguably the biggest addition — in terms of economic impact — is the $1.2 trillion in new infrastructure spending the CPC budget would deploy in its first decade. There's widespread agreement that at least that much is needed to repair the country's seaports, roads, bridges, railways and such. And there's hundreds of billions more needed to update the national infrastructure to make it more green friendly and environmentally sustainable.

So would all this spending lead to a level of debt that would make this plan a non-starter? In a word: no.

First off, the CPC budget will pay for part of itself by returning the U.S. to a mid-century income tax structure. It will add several new tax brackets with higher rates for those making over $1 million a year. There's also a new tax on high-speed speculative trading on Wall Street, as well as a tax on carbon emissions. (Since energy taxes are regressive, the CPC budget also takes 25 percent of the carbon tax's revenue and gives it back to low-income Americans.)

More importantly, the historically low interest rates the U.S. is paying on its debt, the sluggish economic recovery, and our crumbling infrastructure all mean deficit spending could help generate millions of new jobs without increasing the deficit to unsustainable levels. In fact, there's an argument to be made that investing like this now will lead to lower deficits later, as more people earn higher incomes and pay more tax revenues.

Add all of these points up, and EPI projects that, after an initial burst of higher deficits, the gap between spending and tax revenue would actually be lower by the end of the CPC budget's first decade of operation than at the same point under current law. The one caveat Blair and EPI pointed to was the Federal Reserve, which could raise interest rates, pushing unemployment back up. So liberals and Democrats will need to take a firm stance on monetary policy as well as fiscal policy.

The point being, sitting in the offices of Democratic legislators right now is a budget that's essentially the mirror inverse of Ryan's vision. It arguably sits at a happy medium between the ambition of Bernie Sanders' platform and the caution of Hillary Clinton.

If Democrats want a vision to unite behind — something that would tell the American people what the party is fighting for, even if it can't all pass right this minute — they could do a whole lot worse.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’Feature New insights into the Murdoch family’s turmoil and a renowned journalist’s time in pre-World War II Paris

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred