Why Bernie Sanders is right to mistrust the Democratic Party

After the New York primary, the arithmetic is looking very tough for Sanders. But that doesn't mean he has no leverage.

Despite the fact that Bernie Sanders has pulled even with Hillary Clinton in national polls, he went down to a 58 percent to 42 percent defeat in the New York primary. With Clinton's extant delegate lead, the arithmetic is looking very tough for Sanders to be able to win the primary outright.

This naturally leads to speculation about what Sanders might do to leverage his following, should he indeed lose. Democratic Party partisans naturally want him to fall in line behind Clinton, and become little more than a cheerleader.

But this would be foolish. Absent some concessions, there is no reason for Sanders to trust that the Democratic Party would actually work to implement his goals, even partially. He would be wise to extract some concessions before granting his support.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It is of course true that any Republican candidate would be a far worse president than either Sanders or Clinton. But it is also the case that the Democratic Party is not particularly interested in Sanders' social-democratic agenda. When they had gigantic majorities in 2009-10, they only just barely managed to pass a milquetoast health care reform and a too-small stimulus. Their plan to help underwater homeowners was an abysmal failure. They failed to get through a climate bill. They didn't make D.C. a state, or pass paid leave, or sick leave, or drug policy reform, or free college, or a financial transactions tax, or a dozen other things.

There were various procedural obstacles to this, but that's just another way of saying the Democrats didn't particularly care about clearing the institutional clogs (like the filibuster) preventing more quality policy from getting through.

Only very recently has the party begun to halfheartedly and partially disavow the truly wretched products of the Clinton administration, like welfare reform and the 1994 crime bill. They still worship before the false god of deficit reduction. Big cuts to Social Security were just barely avoided by the Lewinsky scandal in the 90s, and sheer Republican intransigence in 2011.

More fundamentally, as David Dayen points out, big-shot Democrats basically believe in the legitimacy of Wall Street, and dislike the steep tax increases that would be necessary to fund a large expansion of the welfare state. (There's also the fact that the actual leader of the party infrastructure is a shill for the payday loan industry.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Clinton has also run quite a conservative primary campaign, attacking the very idea of social insurance from the right, and pushing for little more than minor little tweaks around the domestic policy edges. She's also been reliably atrocious on foreign policy, refusing to come to grips with the repeated failure of military intervention, and all but promising to put Benjamin Netanyahu in charge of the State Department.

At the end of this primary, lots of Democrats will be suspicious of Clinton, and rightly so. And as the winner of a slew of primaries, Sanders will have a legitimate claim to speak for a huge number of Democratic voters. It's only right and proper that he should get some say in what the party will stand for.

So in return for an endorsement of Clinton, Sanders ought to demand a few big policy commitments — perhaps his trillion-dollar infrastructure plan, a public option for ObamaCare, and a plan for free state college, or some other combination. He should not automatically endorse party insiders in congressional primaries, who are often conservative austerians.

Of course, that doesn't guarantee that the party won't try to forget all about that later. But presidents do generally try to keep their promises, and if he can't win, Sanders will have to try something like this if he wants to push the general election leftwards. He's got a fairly strong hand to play — Clinton's popularity numbers are terrible, and she will likely need Sanders voters if she is going to win by a big enough margin to take the House and Senate. If she wants them, she's going to have to make some leftward compromises for once.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Which way will Trump go on Iran?

Which way will Trump go on Iran?Today’s Big Question Diplomatic talks set to be held in Turkey on Friday, but failure to reach an agreement could have ‘terrible’ global ramifications

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue TUI after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

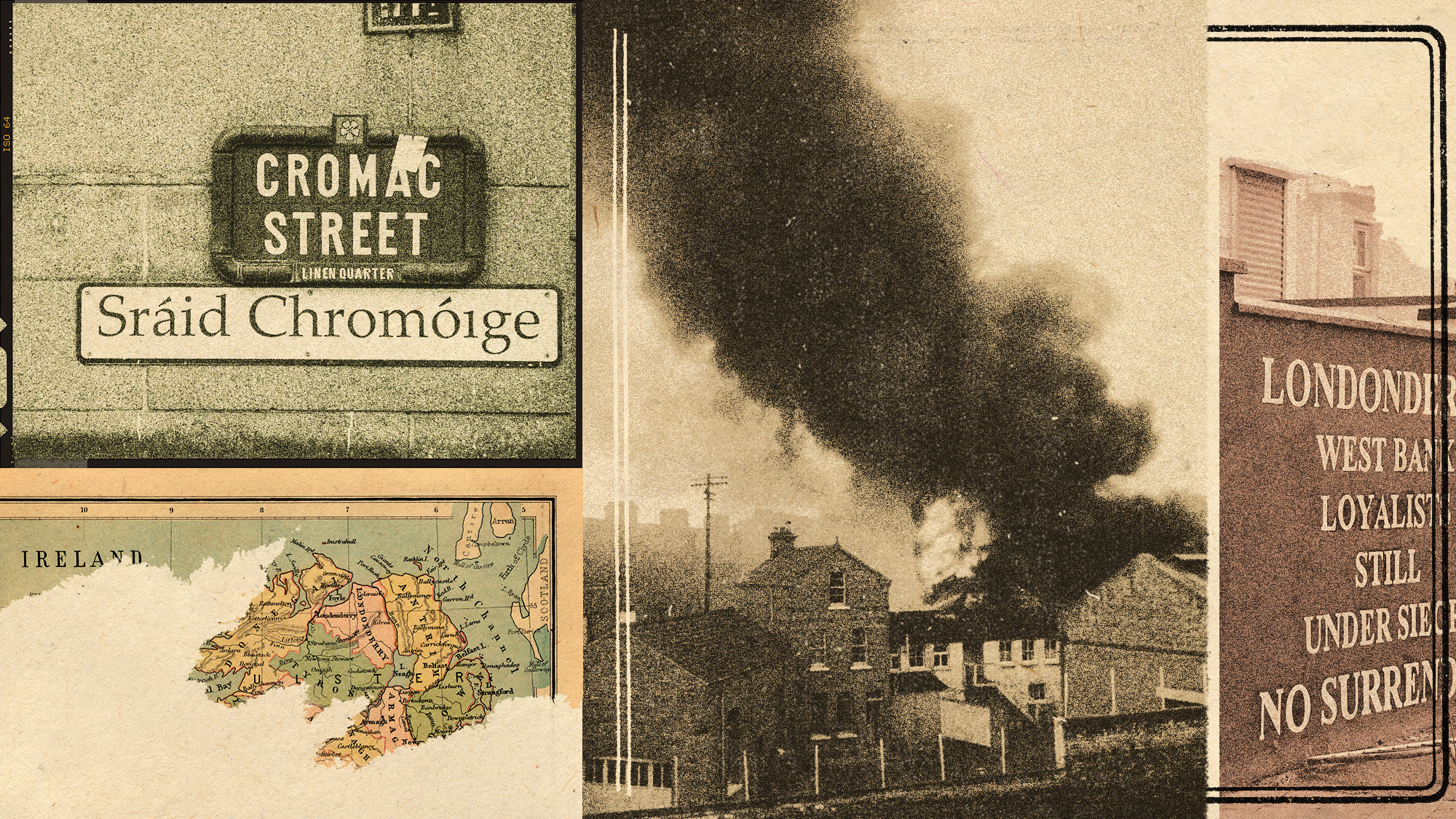

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred