The real reason Bernie Sanders failed

He had a lot of popular ideas, but no real plan of action for bringing them to fruition

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

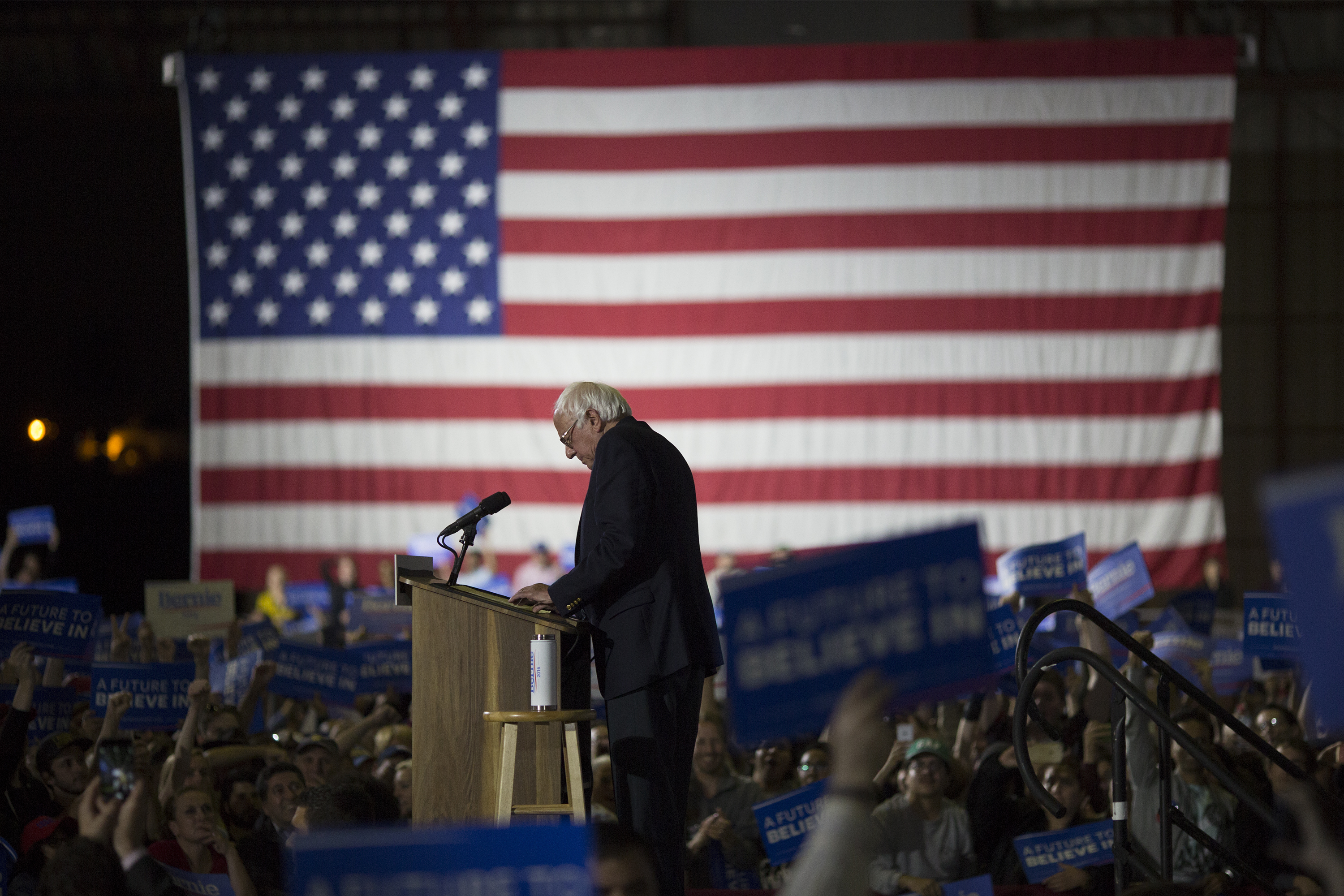

Bernie Sanders is vowing to carry on his fight for the Democratic presidential nomination all the way to the Democratic National Convention in July. He may just do that, too, but he won't win. On Tuesday, Hillary Clinton secured enough pledged delegates to win the nomination even without the help of superdelegates.

Nobody can really be surprised that Clinton clinched the nomination by this point. Certainly Sanders' top aides weren't. Postmortems were already being written before Tuesday about the Sanders campaign, and how Bernie could have beat Hillary if only he had attacked her on her "damn emails" (The Washington Post's Chris Cillizza), or hadn't spent "months painting Democrats as corrupt corporate sellouts" (Amanda Marcotte at Salon), or learned to connect with black and Latino voters earlier (John Wagner, Philip Rucker, and Robert Costa at The Post). Surely more diagnoses will come in as soon as Sanders bows out.

But I don't think any of those are quite right — and neither does the Sanders campaign. Sanders was plenty combative, considering himself wronged and disrespected by the media and the Democratic Party, but "every time Sanders got into a knife fight, aides say, they ended up losing," Politico reports. Sanders got to where he is by being a happy warrior for progressive economics and revolutionary fervor, and there's no reason to believe that bringing up Bill Clinton's sex scandals or Clinton's email woes — as the Sanders campaign considered in the fall — would have helped him more than hurt him.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Tad Devine, Sanders' senior strategist, got closer to the problem. "I don’t think anybody had figured out how to win when we got in," he told The Washington Post. "It was 'How do we become credible?'" Sanders became credible by winning where it wasn't expected, proving that his ideas are actually popular among a sizable chunk of the Democratic electorate. What he failed to do was offer a plausible explanation as to how he would get any of his ideas enacted, especially if one or both houses are controlled by Republicans.

The typical Bernie Sanders supporter wasn't alive in the mid-1980s, when this Wendy's ad was (for some reason) a cultural phenomenon. But it sums up the Sanders shortcoming pretty well:

Sanders has acknowledged that he entered the Democratic race as an issues candidate, without any real expectation of becoming the nominee. That changed in the fall, but coming up with legislative strategies takes time, and Hillary Clinton has had years of planning — and some very high-profile failures — to come up with concrete goals and ideas on how to get them through Congress.

As former "young Hillary hater" Rebecca Traister writes in New York Magazine, "Clinton is a master at identifying problems and coming up with plans to solve them." She continues:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There is seemingly no crisis too small to escape her attention, no subject outside her wheelhouse. When she turns her energies onto bigger issues, her ability to see an interlocking set of concerns and her detailed knowledge about ... everything can sound like a parody of female hyper competence ... Clinton’s holistic view of intersecting challenges and multi-tentacled solutions — tax incentives, subsidies, wage hikes, pay protections — is weirdly thrilling in its expansive perspicacity. But it does not fit on a T-shirt. It does not sound good at a rally. You cannot even really show it on the local news, because it is not as simple as, say, "Free college!" [New York]

Sanders is no spring chicken when it comes to politics, and unlike Clinton, he has executive experience as mayor of Burlington, Vermont. But his entire plan to get huge policy proposals — universal Medicare-for-all health care, tuition-free college, and even more modest ones, like a $15 minimum wage — through Congress was a popular revolution. If the American people rose up and bugged Congress enough, he thought, Congress would listen to them. And when Clinton and other people would note the problems with this aspirational approach, Sanders would accuse them of thinking too small, not "thinking outside the box."

Of course America can do all these things, Sanders would say. Look at Norway — a homogenous country of 5 million with vast oil wealth and no global military commitments. Perhaps government-sponsored health care is possible in the U.S. — it would be really nice not to have to deal with insurance companies, or get rid of student debt — but just because Europe has developed a different system of governing itself isn't proof that America can do it, too. Most European countries still have monarchies, but nobody is suggesting the U.S. decide to anoint its own king.

Bernie Sanders did better than most people expected, including myself and probably Bernie Sanders, too. His self-professed democratic socialism, it turns out, wasn't a deal-breaker. I'm not going to tell him how to end his campaign — that's his call. But the "next Bernie Sanders" might have more success if he or she has more than just big ideas.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred