How Trump and Hannity could have respectfully disagreed with the Khans

When Republicans brought parents whose children had been killed by undocumented immigrants to their convention, Democrats didn't try to discredit or demonize them. But they did disagree with their conclusions.

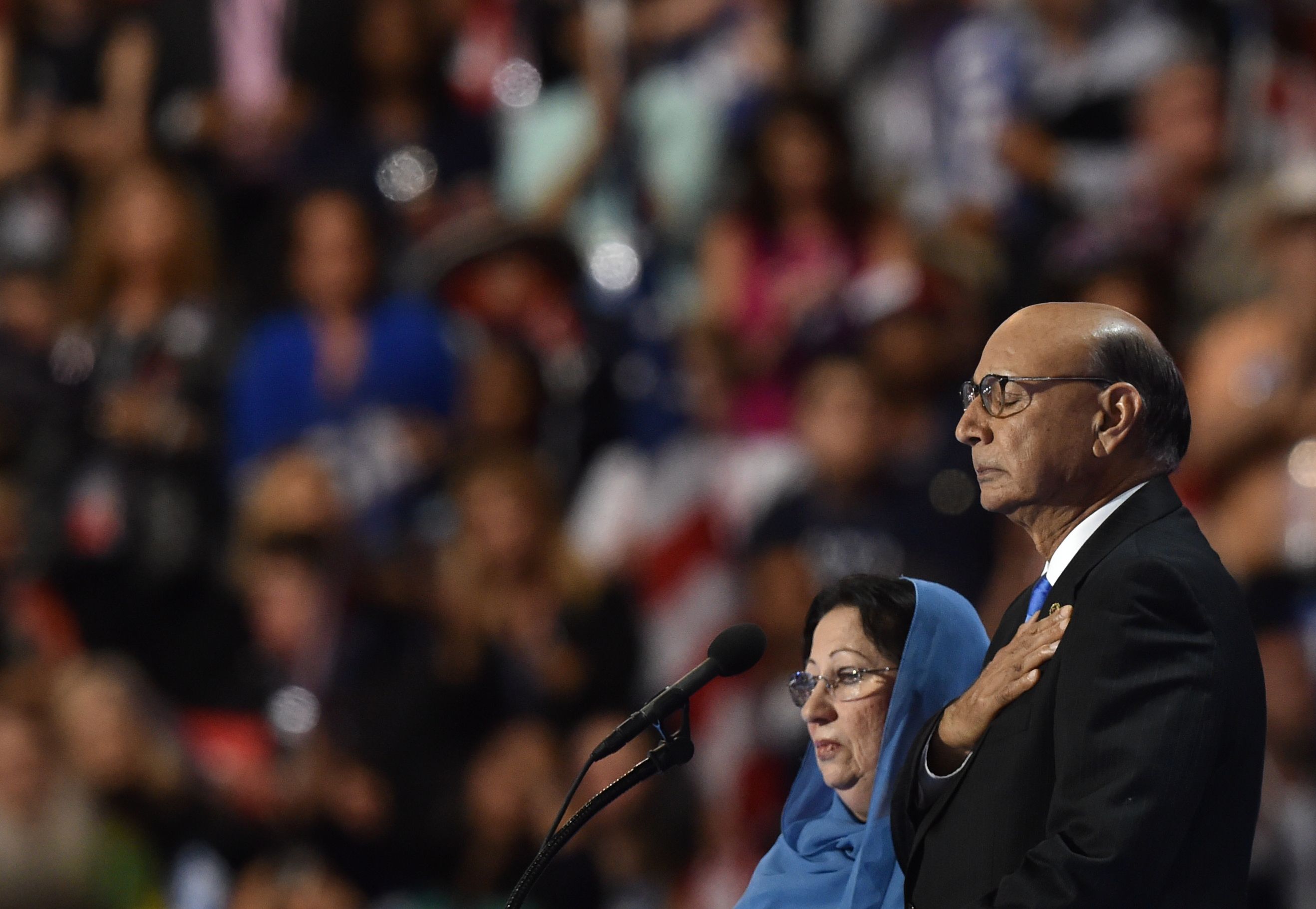

When Khizr and Ghazala Khan appeared at the Democratic convention to criticize Donald Trump for his pledge to bar Muslims from entering the United States and his broader campaign of xenophobia, you might have expected Republicans to refrain from going after the couple. Even apart from it being morally repugnant, wouldn't it be politically insane to attack the parents of a soldier who had died in Iraq? And with the exception of Trump himself (and the occasional voice from the fever swamp), Republicans left them alone. That is, until brave cable news crusader Sean Hannity took up the charge of smearing the Khans. Hannity is now conducting an extended "investigation" into the couple, on the grounds that they're Muslims, and, you know, sharia or something.

We can all agree that Hannity is a particularly odious character, and that the anti-Muslim hatred directed at the Khans from the seedier corners of the right is sickening, if not surprising. But if we step back, there's a legitimate question to be asked: What ought to be the norms we follow when grieving families voluntarily enter our public debate? Should their loss shield them from all criticism, and if not, what kind of criticism is appropriate and what kind isn't?

The simplest answer would be that when someone like Khizr Khan joins the debate (although his wife has made her opinions known, he's the one who has been much more outspoken), no one should feel restrained from engaging him on the substance of what he has to say. If he argues that Trump's Muslim ban is wrong or that Trump evinces no understanding of fundamental American values, it's perfectly fine to argue back that the ban is necessary or that despite all appearances Trump actually has a deep and profound understanding of constitutional principles.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What's unseemly is to answer his charges with a personal attack, as Hannity is doing. That's an old strategy when faced with some ordinary person who emerges as a symbol or spokesperson for the other side; you may recall that when Democrats had a 12-year-old boy who had been helped by the Children's Health Insurance Program deliver their weekly radio address in 2007, conservative pundit Michelle Malkin was so determined to take him down that she traveled to Baltimore to snoop around his house in an attempt to find dirt. Democrats have done it, too: They gleefully noted that "Joe the Plumber" wasn't actually named Joe, wasn't a licensed plumber, and wasn't quite up to date paying those taxes he was so concerned about keeping low.

What that kind of attack really does is say, "You want to be a part of the political debate? Fine, then we'll treat you just like a politician. And that means oppo research." In other words, if you disagree with us, we will try to disqualify and discredit you based on who you are, not on what you have to say. The more one side lionizes you, the more likely it is the other side will try to puncture your story.

To put this in Aristotelian terms (since I know that's what you were waiting for), the power of Khan's case against Trump comes less from logos (logic, facts, and reason) and more from pathos (emotion) and most of all from ethos (the identity of the speaker). The Khans were there at the Democratic convention because of their personal story: immigrant parents who raised a son with an acute sense of patriotism and duty, who joined the Army and then was killed protecting the troops under his command. Had they been just a couple of people with an opinion, they would never have been invited — nor would so many have been so moved by Mr. Khan's words, nor would Republicans wish so dearly that nobody had ever heard of them.

After Trump made some false insinuations about Mrs. Khan (that she was prohibited from speaking at the convention because of her religion), pretty much every elected Republican who was asked about it recoiled in horror from what their nominee said, which is a measure of how different he is from ordinary politicians. "I was viciously attacked from the stage, and I have a right to answer back," he said by way of explanation, but the question is of course not what he has a right to do, but what's right to do.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The fact is that grief, particularly the grief of losing a child, creates its own ethos, its own kind of authority. It doesn't mean that those who bear it into the public square will necessarily see their side carry the day, but it does mean they'll be listened to respectfully and not be attacked personally. That's not a rule, it's a norm, which means that you can go ahead and violate it — but if you do, you can expect that people are going to react negatively. Trump may find that norm an unfair restriction on his unstoppable need to insult and attack anyone who disagrees with him, but if he had just explained why he disagrees with the Khans and left it there, no one would have minded — and they wouldn't have achieved the renown they did.

You may have forgotten by now, but Republicans tried to create the same effect at their convention, by bringing on stage a group of parents whose children had been killed in crimes or car accidents by undocumented immigrants. Liberals didn't try to discredit or demonize those parents; instead, they argued calmly that as awful as their grief is, the truth is that immigrants commit fewer crimes than native-born citizens, and so those cases don't provide much of a guide for what our immigration policy ought to be. No one attacked the families, even if some argued that bringing them to the convention was an inflammatory way to stoke fear and nationalism.

Both parties do this all the time: They're always on the lookout for ordinary people who can stand as representations of their positions and ideas, to take abstract policy arguments and embody them in human exemplars with a story to tell. (Journalists do it too, to an almost obsessive degree). And yes, sometimes they're elevated precisely because those stories place them beyond criticism, or at least beyond a certain kind of criticism.

But that's something that most all of us — with just a couple of exceptions like Donald Trump and Sean Hannity — have little problem with.

Paul Waldman is a senior writer with The American Prospect magazine and a blogger for The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in dozens of newspapers, magazines, and web sites, and he is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics.

-

31 political cartoons for January 2026

31 political cartoons for January 2026Cartoons Editorial cartoonists take on Donald Trump, ICE, the World Economic Forum in Davos, Greenland and more

-

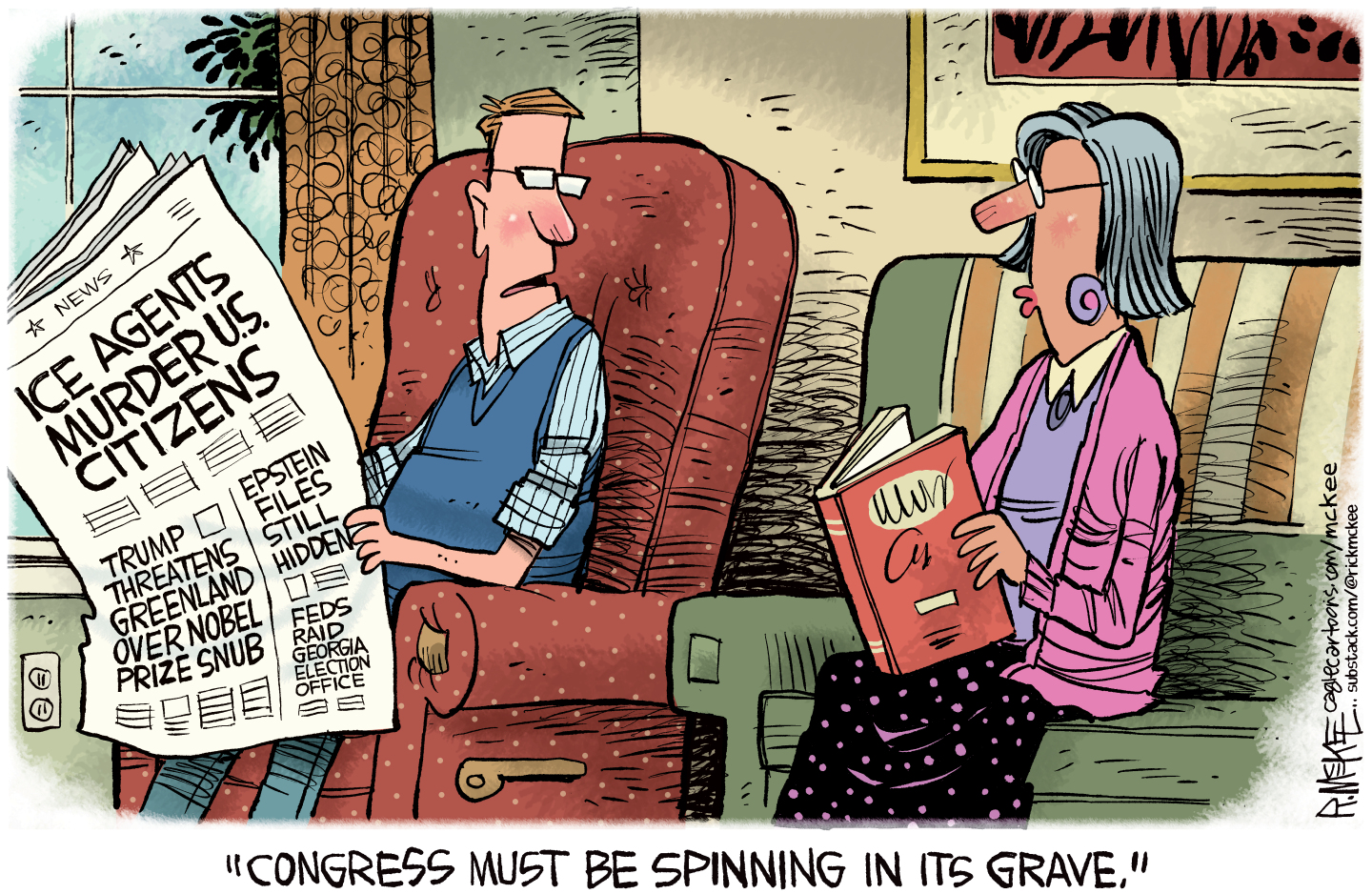

Political cartoons for January 31

Political cartoons for January 31Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include congressional spin, Obamacare subsidies, and more

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred