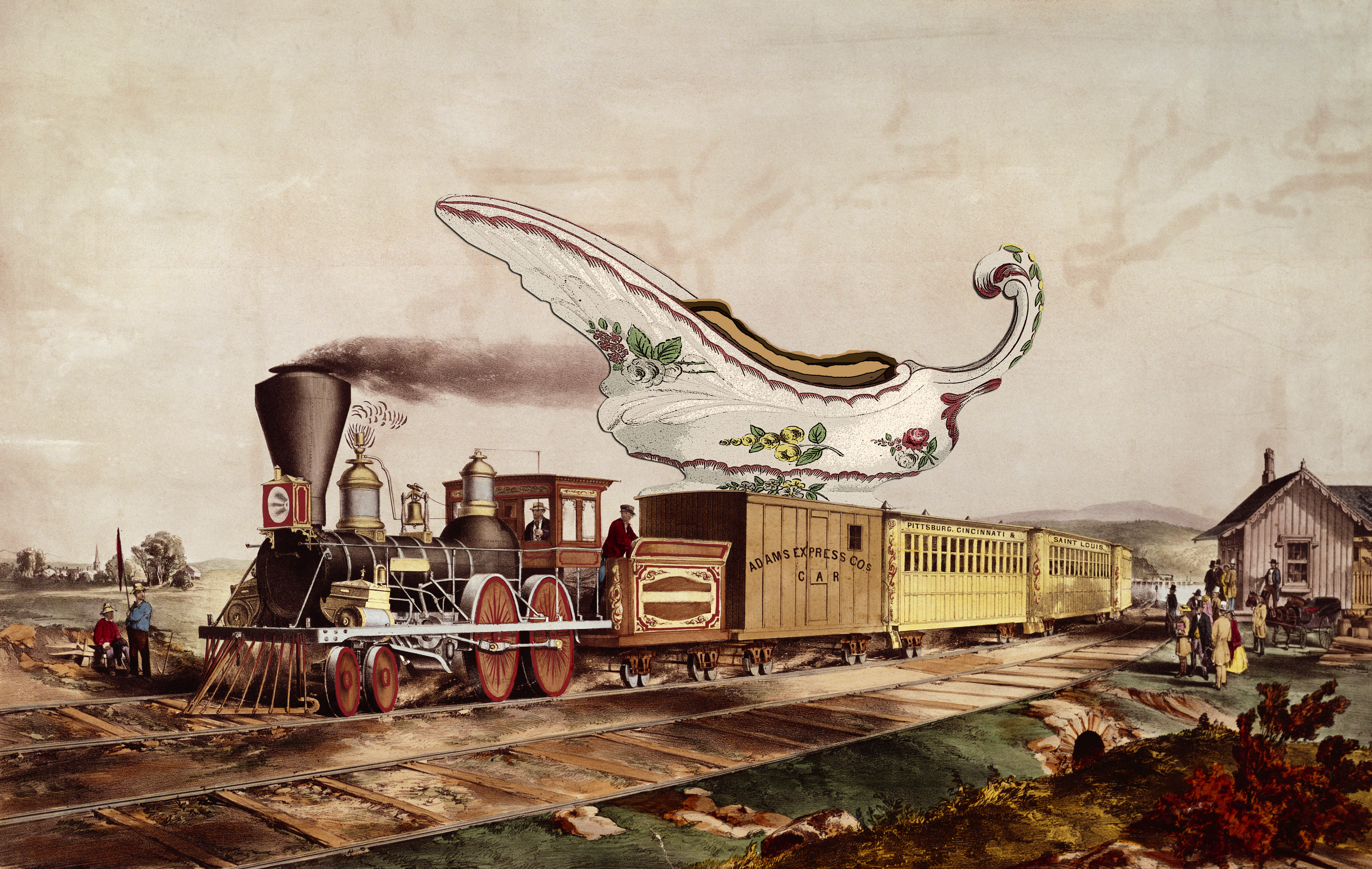

Was there ever an actual train that carried gravy?

On the history and meaning of 'gravy train'

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On September 20, Donald Trump tweeted, "Thank you Kenansville, North Carolina! Remember — on November 8, that special interest gravy train is coming to a very abrupt end!" And every Torontonian reading it thought, "That sounds familiar."

Not just because Trump has used the term before, starting back in May. No, "Stop the gravy train" was a campaign slogan for Rob Ford, whom the world came to know as the crack-smoking mayor of Toronto — an abrasive city councilor who rode a wave of voter resentment to the top job. Donald Trump is similarly fuelling his campaign by focusing anger against people he presents as freeloaders — "riding the gravy train."

But Rob Ford didn't invent the term gravy train, and Ford and Trump are far from the only people of late to use it (and to have it used on them in return). Just in recent days, leaders and members of both the ruling Conservative and opposition Labour parties in the U.K. have been accused of riding the gravy train. So have politicians in Germany, Italy, and South Africa… and, if you look around enough, pretty much everywhere else. So, at one time or another, have lobbyists, consultants, actors, musicians, athletes… Whatever this gravy train is, it sure has a lot of cars and an extensive network of rails.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But what is the gravy train? Was there literally a train that carried gravy? Or is it a thing you find in a restaurant, like a gravy boat but longer? And when did people first start using the term?

Pink Floyd fans may recall the song "Have a Cigar" from the 1975 album Wish You Were Here, where the refrain is "And did I tell you the name of the game, boy? It's called riding the gravy train." But Pink Floyd didn't invent the term. Dog owners have known the brand name Gravy Train since 1959, when General Foods introduced it as the first dry dog food that made gravy when water was added. But General Foods didn't invent the term either.

It might seem as though college boys did. A 1927 list of "Stanford Expressions" in the journal American Speech includes gravy train, defined as "sinecure" (i.e., a paying position requiring little or no work), and notes it as used at Stanford but not necessarily elsewhere in the area. A 1914 copy of Ole Miss, the yearbook of the University of Mississippi, has a list of "Ole Miss as she is spoke" terms, and for Gravy Train puts "Freshman Math???? 'Get off that gravy train.' — Gen. Dorroh." But that doesn't really tell us when gravy and train first came together either.

Some people will tell you that railway men invented the term. There's a mention of the term in a 1910 edition of the Railway Carmen's Journal: "What do you care if someone else is wrestling with a tough proposition. You are all right; you are on the gravy train." The context is not engineers or conductors, however, but maintenance contractors: The gravy train in question is an easy, well-paying piece of maintenance work. An issue of Bricklayer and Mason from the same year uses the term, too: "What a gravy train those I. U. officials ride on!" That's definitely not a literal use.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But those aren't the earliest known uses of the term either. The redoubtable word researcher Michael Quinion has managed to find an instance of it in the Courier newspaper of Connellsville, Pennsylvania, from 1895 — referring to a jail easily broken into and out of.

In fact, no one has found any real evidence for literal trains being the origin of the term. The train likely started out as figurative as the gravy. We can't say that it transferred from gravy boat, either: Although gravy boats already existed at the time, no one used the term gravy boat in a figurative sense like gravy train until the middle of the 20th century.

What we do know is that the gravy came first, and then the train was added. Gravy by itself meaning unearned bonuses and sweet deals is a slightly older term than gravy train, and it has stayed in use to refer to profligacy, especially on the part of governments when they make any sort of expenditure for anyone the speaker holds in low esteem. On the other hand, gravy is also used approvingly for any nice surplus when the speaker is on the receiving end: "Enough to pay the bills, and the rest is just gravy."

Gravy trains seem to run in two directions: When there are two sides of an issue, each may hold that the other is riding the gravy train. Welfare checks or corporate tax breaks? Union wages or executive bonuses? Councilors who hold community events with bouncy castles and popcorn machines, or a mayor who works half days and skips important meetings? Gravy is in the eye of the beholders, and at least some of them may be mistaken.

Which would be fitting, because the word gravy itself seems to have come from a mistake. It shows up in English cookbooks in the 1300s and 1400s apparently as a loan from French gravé (or, as it would equally be written at the time, graué — the letter forms u and v were used interchangeably at the time). The problem is that when you look at the French recipes for the same things, the word is not graué but grané, a word derived from grain but meaning "sauce" or "stew." Thanks to bad handwriting or blotchy printing, or just sloppy typesetting, that n got turned upside down to become a cup u, later a vessel v… perfect for holding lots of that gravy.

James Harbeck is a professional word taster and sentence sommelier (an editor trained in linguistics). He is the author of the blog Sesquiotica and the book Songs of Love and Grammar.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.